Catholic Worker Jeff Dietrich, center, protests in Los Angeles in 2010. (AP/Reed Saxon)

On Aug. 10, my 90-year-old wife and I will celebrate our 50th wedding anniversary by risking arrest and jail time at Vandenberg Space Force Base. In memory of Hiroshima and the ongoing wars in Gaza and Ukraine, we will once again commit civil disobedience.

My life — my real life — began with resistance. The day in 1970 that I refused induction into the U.S. military, refused to murder, bayonet, maim or kill the enemies of my country, was the day that I was reborn into the fullness of life.

From that moment on, I was a felon, a fugitive from justice, and my aspirations of getting a well-paying job and living the American dream had come to an end. As a felon, I could not enter professional life; I could not be a lawyer, or a teacher or a doctor. I could not even be a barber with a felony on my record. My plans of living the comfortable, affluent American dream, as my suburban parents had, collapsed.

So, I stuck out my thumb and hitchhiked across the continent from California to New York with a Jack Kerouac On The Road kind of romanticism, in search of an alternative dream. In retrospect, it was a kind of a quest, a quest to find a vision for my life.

While staying with friends in New York, I visited a bookstore where I encountered a book by Robert de Ropp called The Master Game: Pathways to Higher Consciousness Beyond the Drug Experience, which in retrospect saved my life. It explained several methods of meditation.

Because I had been reading Franny and Zooey by J.D. Salinger at the time, I chose the Jesus prayer quoted in the book — "Jesus Christ, son of David, have mercy on me, a sinner" — as my mantra. You have lots of time while waiting on the road for rides and I thought it would be better to recite the Jesus prayer than reciting the "Snap! Crackle! Pop!" Rice Krispies jingle in my head.

Advertisement

I recited the Jesus prayer when I was lonely, frightened or in awkward situations. I did not know at the time that this mantra was a secret, muffled cry to heaven for my very life.

I was still praying when I finally arrived in Denmark. I was desolate, lonely and cold, missing family and friends. I slept in abandoned trucks and railway cars when it rained, in open fields, behind shrubs, and under park benches when the weather turned nice. I woke up one morning in Spain to find myself in a city dump, with a donkey licking my face.

I took the train to Marrakesh and smuggled hashish in an ornate Moroccan table, but I was still praying as I walked the dark and lonely back roads in Portugal with a flashlight in hand, visiting the spectacular Alhambra in Spain. I prayed as I spent freezing cold summer days in London parks and public libraries because I had sent my winter jacket back home.

I was still praying when I landed back in the U.S.

I fully expected to be arrested for draft refusal when I stepped off the plane from Europe but, much to my surprise and relief (and luck), I was not arrested. I stuck out my thumb with more bluff and bravado than sensibleness — and hit the road again. I had $5 in my pocket, not wanting to wire home for money.

I was still praying when, two days later, I was on an off-ramp outside of St. Louis. Still had the same $5 in my pocket when a Volkswagen van picked me up: "We're goin' to a Peacemakers Conference," they said, "You want to go?"

In 1990, Gary Palmatier painted the “Jesus of the Bread Line” mural, an interpretation of an etching by Fritz Eichenberg, on a wall of the Catholic Worker soup kitchen in Los Angeles. (Mike Wisniewski)

It could have been a rainbow, hippie, dope-smoking gathering, but instead it was a coming-together of legitimate peacemakers who had served prison time for refusing induction into World War II, people who had been beaten on Freedom Rides to the South, and protested every war and weapons system their country could devise. They lived simply, refused to pay federal taxes for war, and they challenged my youthful disdain for seniors.

I was, after all, of the generation who thought that you could not trust anyone over 30 — even though some of the peacemakers were over 50! I was misguided in my thinking because I had never been introduced to folks who had lived their entire lives in an ethical and righteous manner.

Unbeknownst to me, I was meeting a group of Catholic Workers who would change my life.

Though I grew up Catholic, was an altar boy, attended Catholic schools most of my life, I had never heard of Dorothy Day and her radical band of subversive Catholic Workers — people who fed the hungry, clothed the naked, sheltered the homeless, and agitated for peace against the current war in Vietnam.

These young people, from the Milwaukee Catholic Worker, were coming from the trial of the Milwaukee 14, in which their founder, Mike Cullen, led 13 others in burning draft files. When I heard what they had done, a light went on in my soul. I thought this is what Jesus would be doing if he were alive today: feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, sheltering the homeless — and burning draft files.

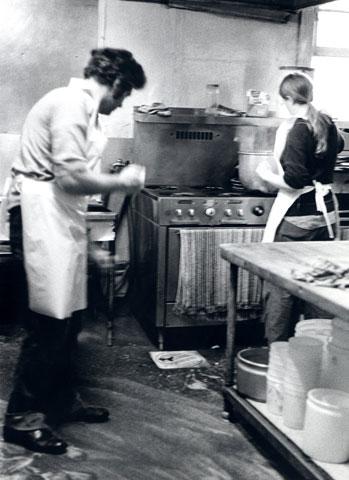

Community members work in the soup kitchen of the Los Angeles Catholic Worker in 1977. (NCR photo/Patty Edmonds)

All at once, my political, anti-war convictions came into alignment with my somewhat-dormant spiritual Catholic convictions.

I was still praying when I returned home and visited my brother in county jail, incarcerated for a break-in. When I walked outside the jail, I encountered a blue and white laundry van with "House of Hospitality'' painted in small letters on the side.

If I had not refused induction, hitchhiked across the continent, traveled to Europe and Morocco, hitchhiked back across the continent, and encountered the Catholic Worker outside St. Louis, I would have walked right past the van, thinking they were selling coffee and donuts to passersby. Instead, I knew that the House of Hospitality was part of the Catholic Workers. I talked to the man handing out coffee and donuts to releasees from county jail; he was Jerry Fallon, a former priest associated with the newly founded Los Angeles Catholic Worker.

I was still praying when I hitchhiked to the location Jerry had given me, dressed in my rumpled cowboy hat and cowboy boots, with my hand-tooled Moroccan purse on my shoulder, and I met Dan and Chris Delany, founders of the Los Angeles Catholic Worker.

Dan asked, "What have you been doing?"

I responded, taking a drag off my freshly hand-rolled Moroccan tobacco cigarette: "Been on the road, man."

But, after some stammering, I was forced to admit that I was just a boring English major. Whereupon I was promoted to editor of the yet-to-be published Catholic Agitator newspaper.

That was an answer to prayer.

Yet I was still praying as Dan and Chis left LA Catholic Worker, in a somewhat acrimonious dispute, soon after I came. A group of long-haired hippie anarchist types then joined me and our community of Catholic Workers in Los Angeles. Not a very prestigious group of folks, but fortunately, I had the good sense to marry Catherine Morris, a former Catholic nun 12 years my senior, who was able to generate and sustain that community. This, too, was an answer to prayer.

Catherine Morris and Jeff Dietrich, spouses and "coconspirators" at the Los Angeles Catholic Worker (Courtesy of Los Angeles Catholic Worker)

For more than 50 years we have created a community on Skid Row in Los Angeles that has stood faithfully for the Gospel principles of justice and peace: We have thrown blood and oil on the steps of the federal building, cut the fence around the nuclear test site in Nevada; we have been arrested countless times.

We have fed thousands of homeless people at our Hippie Kitchen and given out thousands of shoes, blankets, clothes, and tarps. We have lived simply, in our own home, with the poor and homeless, some of whom have even died with us, as we prayed with them in our hospice room. It was another answer to prayer.

We have influenced public policy, highlighting Skid Row as an Ellis Island for the poor and homeless, with tents and tarps proliferating the sidewalks and streets proclaiming that the neoliberal, capitalist system is broken. But this is not success as the world knows it. Christ remains crucified in the poor and homeless of Skid Row, as well as all the poor and homeless throughout the world fleeing war, famine and climate change.

I invite you to practice resurrection through resistance. And through prayer. Those prayers will be answered.

Editor's note: This essay is adapted from Jeff Deitrich's speech in May when he accepted the Berrigan-McAlister Award from DePaul University, given this year to Los Angeles Catholic Worker. Created in 2021, the award honors individuals or organizations whose acts of Christian nonviolence — like those practiced by Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, Philip Berrigan and Elizabeth McAlister — resist injustice, transform conflict, foster reconciliation, and seek justice and peace for all.