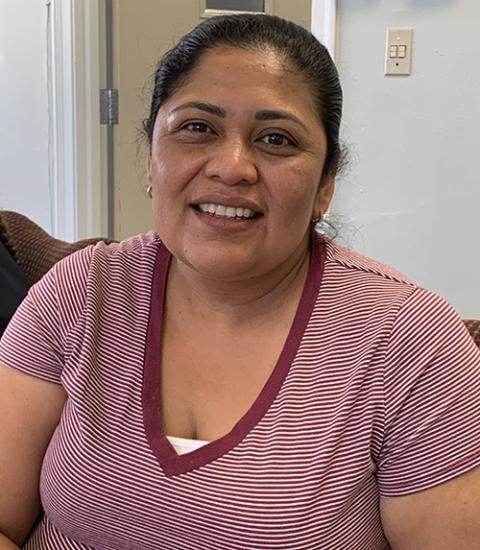

Stephanie Gonzalez and her mother Edith Espinal, wash dishes together in October 2019 in the kitchen of Columbus Mennonite Church, where Espinal has lived for the past two years. Stephanie, who was 16, when her mom entered sanctuary, is now 18, and has gone from quiet high school student to constant activist for her mother's case. (Courtney Hergesheimer/Columbus Dispatch)

The two mothers live a few miles apart, unable to go outside, united by the shared companions of fear and persistence. While millions of Americans are still adjusting to the social isolation brought on by the coronavirus pandemic, Edith Espinal and Miriam Vargas have been strangers to what is considered normal for more than two years now. An invisible virus didn't drive them into seclusion. What has the women locked down behind unfamiliar walls is a fierce determination to keep their families together.

The undocumented immigrants in Columbus, Ohio, are not at home waiting for elected officials to announce an end to quarantine. Both women are living in churches where they found sanctuary after receiving deportation orders. Espinal, a native of Mexico, has been living inside Columbus Mennonite Church for more than 900 days. Vargas, who left Honduras 15 years ago, has been at First English Lutheran Church for almost 700 days. The soft-spoken mothers, who have five children between them, are officially considered fugitives under the law.

Their lives are a daily act of moral resistance, and a testament to improbable hope, during an era when President Donald Trump has given Immigration and Custom Enforcement, or ICE, vast power to detain and deport migrants who previous administrations did not view as a threat. Parents who have lived in the United States for many years, held jobs, paid taxes and are raising their children have been swept up in the Trump administration's intensified enforcement regime.

Edith Espinal, center, and her family; from left to right is Espinal's son Isidro, 23; husband Manuel Gonzalez; son Brandow, 21; and daughter Stephanie, 18 (Provided photo)

"This is the country where my children were born, and it's the only country they know," Espinal said during a recent phone interview. "I want my children to have opportunities for a better future. The truth is I can't even imagine going back to Mexico. My family is here."

There are 43 immigrants living in sanctuary across the country, according to Church World Service, a national advocacy organization that is a leader in the sanctuary movement. ICE has not entered a house of worship since 2014, due in large part to an Obama-era immigration policy that identifies them as "sensitive locations."

During the hard hours, Espinal, 43, draws strength from her Catholic faith. A prayer that she turns to in darker moments is the Magnificat, drawn from the Gospel of Luke. The well-known verses provide both spiritual and political sustenance for those struggling against the powerful, a chance for a mother confronting long odds:

He has shown might with His arm

He has scattered the proud in the conceit of their heart

He has put down the mighty from their thrones,

and has exalted the lowly

He has filled the hungry with good things

and the rich He has sent away empty.

"Persistence is the word that comes to mind when I think about Edith," said Joel Miller, pastor of the Mennonite church that houses Espinal. Along with her resilience, Miller has also watched how the lengthy isolation has taken a grinding toll.

"This is just incredibly hard," he said. "The mental health aspect of this is a real struggle, and her physical health has suffered since she has been in here. What anxiety can do to the body is pretty cruel." Ohio's shelter-in-place regulations mean she can no longer look forward to in-person visits from her children, two sons in their 20s and an 18-year-old daughter, all U.S. citizens.

Espinal ended up living at Columbus Mennonite after a legendary local activist, the late Rubén Castilla Herrera, approached Miller to see if his congregation would take her in as she faced a deportation order. The pastor was receptive and after polling his congregation found strong support. The board voted unanimously in favor. Menonnites are shaped by a historical memory of being a persecuted religious minority, Miller said, and that shapes the denominations' moral imperative to provide sanctuary.

What church leaders call "Team Edith" — about a dozen advocates for Espinal from the congregation and the community — meet twice a month on Tuesdays. The meetings continue now over Zoom. Miller said the church will keep supporting Espinal for as long as she can endure staying in sanctuary, but acknowledges that everyone is hoping for a breakthrough. A new president could potentially shake up the landscape of immigration enforcement. "This election year could be a watershed moment," he said.

There is cautious optimism that the coronavirus crisis could potentially offer at least some protection and freedom of movement for Espinal and Vargas. In a March letter to Congress, ICE officials notified lawmakers that the agency will "delay enforcement actions" because of COVID-19, and the agency said it would "not carry out enforcement operations at or near health care facilities, such as hospitals, doctors' offices, accredited health clinics, and emergent or urgent care facilities, except in the most extraordinary of circumstances." When ICE announced recently that the agency would accept stay of removal requests from undocumented immigrants by mail — rather than requiring an in-person meeting — the immigrants' legal teams filed a request.

Miriam Vargas (Provided photo)

'It's hard living like this'

From the middle of March until just recently, Miriam Vargas spent her time in sanctuary at First English Lutheran fighting fevers, headaches and muscle pain. "I've never been so sick in all my life," Vargas, 43, said in a phone interview. "I do think I had the virus. This really scares me." Sally Padgett, the church's pastor, was also seriously ill and self-quarantined for nearly six weeks, convinced she had COVID-19.

But a specific stay of removal request from Vargas that would give her the freedom of movement to seek emergency medical care if necessary, and take measures to protect her family from COVID-19, was denied last week. The same request filed by Espinal's team is still pending.

Vargas left Honduras in 2005, fleeing widespread violence and limited job opportunities. The country has the highest child homicide rate in Latin America. When she entered the United States, Vargas settled in Columbus and had a six-month work permit. Further notification she expected to receive on her immigration status never arrived at her address, Vargas says, and she kept working.

In 2013, as she neared her apartment with her daughter, an immigrant enforcement agent stopped her. Vargas, then pregnant, was fingerprinted and told she had to check in with immigration officials every six months. Those meetings lasted for five years. A deportation order arrived in 2018.

Her request for amnesty in the United States denied and facing deportation, Vargas was running out of options. Advocates began looking for a church to house her. Vargas visited Espinal, already living in sanctuary, for advice. Through interfaith advocacy meetings organized by Faith in Public Life in Columbus (full disclosure: I work in the organization's Washington, D.C. office), Padgett, the pastor of First English Lutheran, learned about Vargas' situation.

Padgett took the idea to provide sanctuary to her predominately African American congregation in a gentrifying neighborhood. The church quickly rallied behind the immigrant.

"Providing sanctuary is an extension of who we are as a faith community," Padgett said. "One of the beautiful things is to see how the neighborhood has embraced Miriam. There are some people who come to church now because of her. It's opened a door to people who care about this not just as a political issue, but as a faith issue."

Vargas spends her days caring for her two young daughters, both United States citizens, an 11-year-old and a 6-year-old, who has autism spectrum disorder and fragile X syndrome. She loves cooking, especially flour tortillas called pastelitos.

"It's hard living like this and not being able to leave, work or live a normal life," Vargas said. "I'm a person who came here looking for an opportunity in this great nation. My dream is to leave sanctuary and not be followed and persecuted. I'm not a criminal. I'm just an undocumented person."

Vargas, who was raised Catholic, leans on her faith. "I'm around people who have faith and big hearts. That helps me grow in my faith."

Rubén Castilla Herrera translates for Miriam Vargas at the First English Lutheran Church in Columbus July 2, 2018. Vargas, from Honduras, is staying at the church in sanctuary so she can be with her daughters and not be sent back home where she feels threatened. (Eric Albrecht/Columbus Dispatch)

Disappointed by the diocese

In the past year, advocates for Vargas and Espinal have started to work more closely. Before the coronavirus hit, advocates for the immigrant mothers had planned a protest and lobby day in Washington at the end of March. Both women also communicate with other immigrants in sanctuary churches across the country through a weekly Zoom call organized by the National Sanctuary Collective, a network of immigrants, advocates and attorneys. The calls are part emotional check-ins, fellowship time and discussion of advocacy strategies.

While diverse religious denominations publicly support sanctuary, Catholic dioceses have largely opposed to giving immigrants shelter in churches. Espinal is disappointed with the Columbus Diocese.

"I have not gotten a lot of help from them," she said. "I wish I had more support. I have given money to the Catholic Church, all my kids were baptized, received their first Communion and were confirmed in the church."

The Columbus Diocese declined an interview request for this article, but said in a statement that "although we do not advocate for the breaking of laws, we urge a more humane enforcement of immigration laws in a way that keeps family members together."

The diocese noted its leaders have in the past appealed to ICE for a review of Espinal's case. "We are grateful to the members of the Catholic community in Columbus who continue to provide spiritual, emotional and material support to Edith. We hope for the day that Edith and many others living in the shadows can build lives for themselves and their families free of doubt and fear," the statement said.

In a petition sent to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, immigration activists have asked conference leaders to meet with ICE officials in Washington and advocate for Espinal's request for a stay of removal.

The U.S. bishops' conference did not comment on the details of the petition request. Ashley Feasley, the policy director for the bishops' Migration and Refugee Services office, said in an email that while she was unfamiliar with the details of Espinal's situation, her case "illustrates what we know about President Trump's Executive Orders from 2017, which radically broadened who would be considered a target for interior enforcement by ICE and has made immigrants feel particularly scared and isolated in their communities."

If Espinal has not received the kind of public support she wants from the Columbus Diocese or the bishops' conference, individual Catholics, especially women religious, are consistent advocates for her.

The Dominican Sisters of Peace in Columbus has raised several thousand dollars for the mother's legal fees over the years, are lobbying lawmakers on her behalf and are present at prayer vigils. "We seriously considered taking Edith in our motherhouse, but we don't have a lot of room and there is a wait list for sisters moving in," said Sr. Gemma Doll, who lives in community with about 80 retired sisters.

The question of whether the Catholic Church should embrace sanctuary as a pastoral and advocacy response to heightened threats against undocumented immigrants can't be understood in simple terms, according to Neomi De Anda, an activist and religious studies professor at the University of Dayton.

While dioceses are wary of supporting sanctuary given the legal sensitivities at play — and prefer advocating for more long-term solutions such as comprehensive immigration reform — De Anda points to a decentralized network of lay Catholics, priests and women religious across the country who do provide various forms of sanctuary for immigrants, even if those cases are not publicly known.

"When we hear 'the church' we often only think about the hierarchy or parishes," said De Anda, president* of the Academy of Catholic Hispanic Theologians of the United States. "But there are so many structures to being Catholic, and we have to amplify our thinking about what it means to provide sanctuary."

One example is the Franciscan-run Holy Cross Retreat Center in New Mexico, which is providing sanctuary for an immigrant, according to Church World Service.

Even as current political and ecclesial divides over sanctuary are sharp, the concept stretches back centuries in Catholic history. "This is our tradition even if we've forgotten about it," said Leo Guardado, a Fordham University theology professor who is writing a book about sanctuary.

At a church council in 343, while bishops did not directly use the word sanctuary in their deliberations, they spoke of welcoming those who seek the "mercy of the church." Guardado notes this is what we would understand today as sanctuary.

Over the next millennium, he said, exceptions were raised, excluding certain people seeking church protection, and as asylum law developed under the modern nation-state the tradition of church asylum was overshadowed by the legal architecture of secular human rights.

Advertisement

But even in more recent decades, church sanctuary played an important role as Salvadoran refugees fled the civil-war ravaged nation in the 1980s. By the middle of that decade, hundreds of Catholic churches, theology schools, monasteries and campus ministries were providing sanctuary to Salvadoran immigrants.

"Sanctuary is any sacred space where the community comes together and protects. It's not about a building," said Guardado, who formerly worked in the Tucson, Arizona, Diocese and encouraged priests to support sanctuary as a means of giving tangible witness to the church's teachings.

"It's about a community that walks with people," he said. "Sanctuary can become a vehicle for back channel negotiations with the government. It buys time. It's not a long-term solution, but it's an interruption to systemic violence."

For Espinal and Vargas, the clock continues to tick toward an uncertain future. Their faith and determination remain strong despite the prospect of more isolation.

"I'm a mother and I'm fighting to keep my family together," Espinal said. "I want people to know I'm not going to stop fighting."

Vargas insists that if she could ever meet with the most powerful person in Washington, she has a message ready. "I would tell President Trump to think as a father, and not as a president. Don't separate families."

[John Gehring is Catholic program director at Faith in Public Life, and author of The Francis Effect: A Radical Pope's Challenge to the American Catholic Church.]

*This story has been updated to specify that De Anda is the president of the Academy of Catholic Hispanic Theologians of the United States.