Pope Benedict XVI reads his resignation in Latin during a meeting of cardinals at the Vatican on Feb. 11, 2013. (CNS/L'Osservatore Romano)

It is not an accident that one of the most important social theorists, Max Weber, decided to study the dynamics of political and bureaucratic power after spending some time in post-Vatican I Rome. The papacy is about the history of the growth of a papal apparatus more than a speculative theology of the papal ministry. There is no possible understanding of the evolution of the Petrine ministry, of the office of the bishop of Rome as pope of the Roman Catholic Church, without understanding the constellation of offices, ministries, prelatures, and ecclesiastical or secular appendixes revolving around the successor of Peter.

Now, one of the most important recent additions in the constellation of offices that orbit the papal office is the so-called "pope emeritus," a title that Benedict XVI created for himself after his decision to resign. He made the decision some time in 2012 and announced it to the world — in a speech delivered in Latin — on Feb. 11, 2013.

The "emeritus" as an institution was created on the fly in those hectic weeks right before the conclave that elected Benedict's successor, Pope Francis. It was created without the usually and frustratingly slow, partly visible and partly invisible process of making structural changes in the Vatican. The new institution was largely improvised, with no recent tradition to count on, and entirely left to the "pope emeritus" to regulate himself.

The issue is the freedom of the bishop of Rome in his ministry, a ministry of unity of the church, free from undue interference external or internal.

The conclave that elected Francis was extraordinary also because usually the election of the new "father" follows a few days after the burial of the predecessor: something like the demise of the father that creates the necessary space for a new one. This could not happen in 2013.

All that said, the institution of the "emeritus" — which from an ecclesiological point of view should be called the "bishop of Rome emeritus" and not "pope emeritus" — has largely worked since March 2013. Benedict and Francis have a relationship that is perceived as good by the public: In this sense, the movie "The Two Popes" captures something real of the exchange that happened in the complicated and unprecedented transition of power, a transition symbolically not yet consummated.

Over the course of this protracted transition, in the last few months there have been two major incidents. The first was the publication in April 2019 of a long essay, signed by Benedict XVI, that "explained" the sex abuse crisis in the Catholic Church by dismissing all that scientific findings and investigations tell us about the genesis of the scandal, and focusing on a social-political narrative that blames the upheaval on the 1960s.

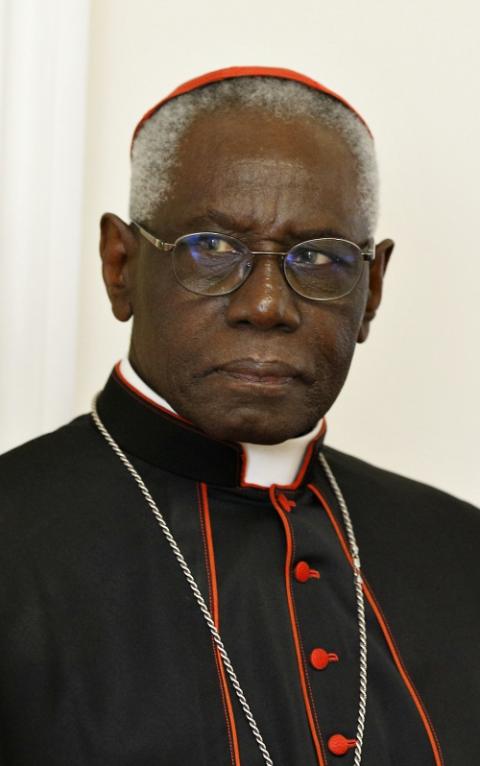

Cardinal Robert Sarah, prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Sacraments, is seen at the Vatican Jan. 14. (CNS/Paul Haring)

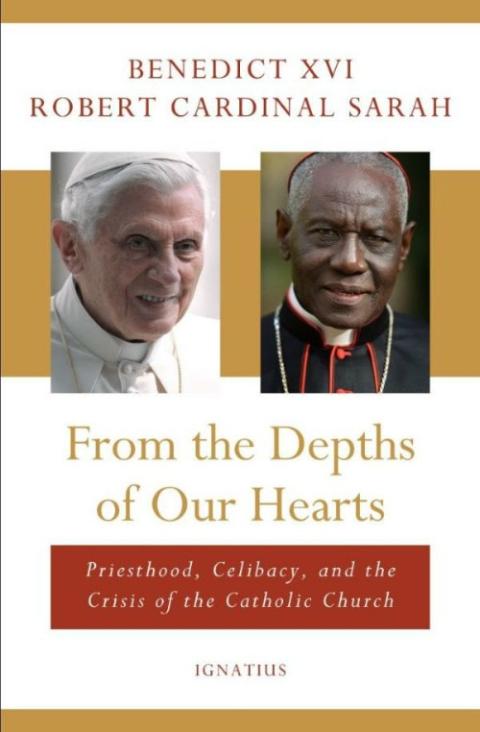

The second, this week, was the announcement of the publication of a book together with Cardinal Robert Sarah, prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, a post to which he was appointed by Francis on Nov. 23, 2014. Benedict since has denied any intention to be a co-author, according to news reports, and has further asked that the publishers remove his name from the tome.

In response, Sarah released a letter from Benedict that told the cardinal to make whatever use he wished with a paper Benedict wrote years ago, in an entirely different context. It is becoming increasingly clear that the cardinal and those who assist Benedict may have taken advantage of trust extended to them by an old man.

The book is a defense of clerical celibacy in the Catholic Church and evidently a response to the debate that took place in the preparation and celebration of the synod for the Amazon region of October 2019.

Beyond the book

This is an incident not because of what the book says on clerical celibacy. On that issue, clear inconsistencies exist: between what this book seems to say and what theologian Joseph Ratzinger used to say; with what Benedict XVI as a pope decided by welcoming conservative married Anglican priests into the Catholic Church; with the tradition of the church that has always had married priests in the 23 Oriental Catholic Churches in full communion with the bishop of Rome; with the documents of Vatican II itself.

The issue is not even whether this is an intentional attack against Pope Francis. The issue, objectively, is the freedom of the bishop of Rome in his ministry, a ministry of unity of the church, free from undue interference external or internal.

There is a deep irony here. For all the talk about maintaining clerical celibacy, the Catholic Church at Vatican II had already changed one fundamental rule in the ministry of bishops that has to do in some ways with the marriage-like and monogamous (according to the Fathers of the Church in the early centuries) relationship between local churches and their top cleric, the bishop. The Second Vatican Council opened the way for the mandatory resignation of all ordinaries at a certain age.

Advertisement

During the post-Vatican II period, Pope Paul VI set the age at 75 and enforced more rules determining the resignation of prelates for reasons of age in the Roman Curia and the exclusion of cardinals older than 80 from the conclave to elect a new pope.

Now, some elements of a functional technocratic mindset took over at Vatican II in the bureaucratization of the bishops' ministry. But at least the rules governing the resignation of bishops were discussed, updated periodically and they have become part of the life of the church today. Many Catholics — and all the clergy — know the "expiration date" for their bishop.

On the other hand, the rules for the resignation of a bishop of Rome, the pope, were never discussed, not at Vatican II, not ever. The council facilitated the option that a pope would resign (an option always available in theory according to canon law), but that option remained a taboo until 2013, also because of the example set by Pope John Paul II in his theologically and mystically argued refusal to resign.

Now, at more than 50 years from Vatican II, this situation of uncertainty is one of the unintended consequences of the council. It is one issue on which Ratzinger did not — as he usually did — follow the path of a narrowing of the import of the council's decisions, but on the contrary accelerated well beyond what most Catholics could imagine, at least in 2013.

The fate of the institution of the "emeritus" was left to the emeritus himself: Just as no one is in charge of accepting the pope's resignation, no one was in charge of telling Benedict XVI what he could or could not wear, where he could live, what kind of entourage he could have. The assumption was the new institution could regulate itself.

No matter what the real intentions of Ratzinger are, he has become part of a narrative in which traditionalists want to 'defend' celibacy by weakening the unity of the church.

Here, the church pays the price of a certain myth about the history of the successful liberation of the papacy from external constraint — the kings and emperors, the Roman nobility, the Italian shadows. The fact is that there is no more exacting emperor for the church today than the public in its "passive democratic" access to the church through media and social media. There is no way to overestimate the importance of the relationship between the papacy and modern media.

This book on celibacy was not an off-the-cuff remark, but a well-planned operation with translations in multiple languages. It seems that the only kind of regulation comes from the mediatic-political market in which the "emeritus" operates with the help of his handlers. The papacy is a lonely business, but the pope is almost never alone. This is even more true for the "pope emeritus," whose age and health demands near constant attention. He is surrounded by an entourage who took great care — in the months before the announcement of the resignation — in protecting their status and position in the Vatican.

The problem with 'emeritus'

The problem with the "emeritus" is that the power associated with the leadership in contemporary religion, included in the Catholic Church and especially for the office of bishop of Rome, is no longer exclusively a religious power legally codified. This is why this kind of intervention constitutes an illegitimate form of pressure on the one pope. No matter what the real intentions of Ratzinger are, he has become part of a narrative in which traditionalists (I am not saying conservatives because conservatives would have more respect for the papal office) want to "defend" celibacy by weakening the unity of the church.

(CNS/Ignatius Press)

It must be noted that in the United States, the perception of this latest pronunciamento is, once again, quite different from the way it is perceived in Europe, where there exists far less resistance to Francis than is evident in America. Given the acceptance among some U.S. bishops and conservative Catholics of such anti-Francis propaganda as former nuncio Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò's letter of August 2018, the church here continues to come dangerously close to a situation that looks like a call to schism.

It is hard to deny that in the eyes of those who do not like Francis' teachings, there is a parallel teaching being written. This is, in the long run, a puzzle for historians and theologians who will have to figure out when Benedict's pontificate really — not canonically — ended.

In the short term, this book seems like a preemptive move — and different from the April 2019 article on the abuse crisis. Francis never published a book or an encyclical or an exhortation on priestly ministry and celibacy. In the synodal process, the pope has a role as presider of the bishops' synod that the "emeritus" does not have. Francis' post-synodal exhortations have not strayed from what was discussed and decided by the synods themselves.

This incident goes beyond the walls of the Vatican and the invisible boundaries of the virtualization of Catholicism in the media and social media. The symbolism of the "emeritus" retiring in a monastery in the Vatican meant very little for those Catholics for whom Benedict XVI never really retired. The "emeritus" promised prayer and silence. They are disobeying Benedict, or Benedict is disobeying himself, or, as now seems likely, some prelates opposed to Francis have sought to hide their plots in the mantle of the emeritus.

One wonders what kind of example the "bishop emeritus" of Rome is giving to the hundreds of diocesan bishops emeriti around the world. The 2004 directory for emeriti, Apostolorum Successores, published by the Curia Congregation for Bishops, made clear that "the Bishop Emeritus will be careful not to interfere in any way, directly or indirectly, in the governance of the diocese. He will want to avoid every attitude and relationship that could even hint at some kind of parallel authority to that of the diocesan Bishop, with damaging consequences for the pastoral life and unity of the diocesan community." Benedict XVI taught, in his own way, his successor Francis how to be and not to be pope. Catholics hope this is true also for the next emeritus.

We all remember how some bishops' appointments were made and announced during the very last days of John Paul II — decisions of which the dying Karol Wojtyla was most certainly unaware. Today, we still assume that the "emeritus" is still able to make decisions about the way his name is used. But it is hard to know for sure. Not only is there still no canon law concerning the situation created by an incapacitated pope, the Catholic Church evidently also needs a law concerning the situation created by an incapacitated "emeritus" and his entourage. This is clearly something that will be possible to address at a moment when the Vatican will be able to legislate without giving the impression of limiting a living "emeritus."

We will never know officially if anyone in the Vatican was informed about all this before the tactical leak to the press. The role of the official Vatican media these days is to avoid any impression of a chasm between the pope and his predecessor. There are some who are acting responsibly in all this, and others who aren't. Shielding themselves behind the "emeritus," there are responsibilities that unfortunately escape the scrutiny to which the papal ministry and any other pastoral ministry in the church are and should be subject.

[Massimo Faggioli is a professor in the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at Villanova University.]