A portion of "The Feast of the Gods" (circa 1630) by Jan Harmensz van Biljert (Wikimedia Commons/CC0 1.0 Universal/©Photo RMN/Stéphane Maréchalle)

Days after the opening of the 2024 Paris Olympics, Christians were still angry, convinced a scene involving drag queens was intended to mock Leonardo da Vinci's "The Last Supper." Even though the ceremony organizers quickly apologized, and even though the ceremony's director, Thomas Jolly, explained that the scene was inspired by 17th-century Dutch artist Jan Harmensz van Biljert's "The Feast of the Gods," depicting a Dionysian revel, the condemnations kept coming.

Some accused the organizers of offering an insincere apology. People sent threats and abusive messages to DJ Barbara Butch, who was involved in the performance. When parts of Paris were struck with an electrical blackout a day after the event, former Tyler, Texas, Bishop Joseph Strickland claimed that this was divine retribution. Bishop Robert Barron of Winona-Rochester, Minnesota, called the scene a "gross mockery." Right-wing political figures also weighed in, with U.S. House Speaker Mike Johnson calling the performance declaring that the "war on our faith and traditional values knows no bounds today."

It is hardly the first time that conservative Christians have cried mockery, persecution or even demonic activity in response to a cultural phenomenon. Remember the rage over the movie "Dogma"? Or, a little further back, over "The Last Temptation of Christ"? Yet both those movies encouraged thoughtful engagement with the complex phenomenon of faith and the significance of the Christian story.

Knee-jerk angry reactions to any representation of Christianity in art that is not cardboard-cutout pious indicate both confusion over the nature of art and a failure to engage thoughtfully and critically with the broader culture. And Christian rage at drag queens representing a Gospel scene indicates that many have forgotten what it means to live that Gospel in a diverse and rapidly changing world.

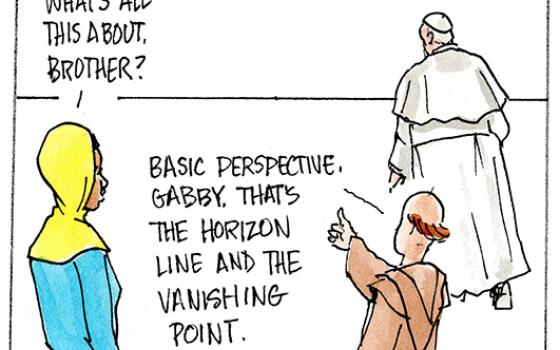

It's still a little unclear whether the ceremony organizers had "The Last Supper" in mind. But even if they did draw on Da Vinci's famous work for inspiration, Christians should not perceive this as mockery. Art alludes to other art, comments on it, engages with it. This is the case with work that represents serious or sacred events as well as with art that is overtly playful or secular.

Da Vinci's painting is not a religious object anyway, and is part of the cultural public domain. Just as we treat ancient Greek myth as a cultural touchstone without worshiping the Greek pantheon, people can reference the art of the European Renaissance as formative and meaningful. These are not "outsiders" attacking our Christian faith. Western Christendom is the cultural heritage of France, secular nation or not, so of course they're going to riff on their own artistic artifacts.

Some works of art, whether people like it or not, have become essential to a broad lexicon of self-commentary. "The Last Supper"— like the "Mona Lisa," "The Birth of Venus," "The Scream" and "American Gothic"— is one of those artworks that people imitate, allude to, meme and, yes, parody. But parody does not always mean mockery. Memes of "American Gothic" aren't mocking the painting itself, nor the culture it represents.

Visitors are pictured in a file photo looking at Leonardo da Vinci's "The Last Supper" on a refectory wall at Santa Maria delle Grazie Church in Milan. (OSV News/Reuters/Stefano Rellandini)

Considering how often "The Last Supper" has been mimicked — in the television shows "Lost," "The Simpsons" and even the notoriously crude "South Park" — why did people decide to take umbrage in this instance? If it was the presence of drag queens and other queer pop culture icons that got Christians upset, perhaps Christians should ask themselves why they think this was a bridge too far. Do Christians really believe the mere presence of a queer person is blasphemous or demonic? Are Christians incapable of seeing the image of God in LGBTQ+ bodies?

I am reminded of the furor over Andres Serrano's photograph "Piss Christ" in the late 1980s. Religious and political leaders have been denouncing the work for over 30 years, even though the artist, who is Catholic, said that it was intended to represent the brutality of what Jesus went through. "Maybe if 'Piss Christ' upsets you, it's because it gives some sense of what the crucifixion actually was like," he said. Art critic Sister Wendy Beckett, though unimpressed with Serrano's artistry, agreed that the photograph was not blasphemous, but instead represented "what we are doing to Christ."

There are valid reasons to object to mockery of religious traditions, even when it's intended playfully. Simplistic piety, blind obedience and fear of questioning are fatal for personal and communal flourishing, but a rejection of the sense of the sacred is as well.

But maybe we need to be more critical of the notion that beliefs are deserving of automatic respect, simply because they are religious or deeply held. If a person's beliefs are morally questionable, do we still need to respect them? Or what about when a belief system has been used to harm or bully others? For those who have been systematically excluded or silenced, mockery can sometimes be an act of liberation.

Knee-jerk angry reactions to any representation of Christianity in art that is not cardboard-cutout pious indicate both confusion over the nature of art and a failure to engage thoughtfully and critically with the broader culture.

When it comes to religious demographics that are in a minority position or at risk of persecution, sensitivity is needed, since even light-hearted spectacle can be symptomatic of a larger intention to dehumanize. There have been times and places where Christianity was one of those persecuted minority religions. Graham Greene's novel The Power and the Glory depicts such a culture: the Mexican state of Tabasco where, in the 1930s, Catholicism was illegal. In the novel, Greene's unnamed "whisky priest" is on the run from the authorities, while still trying to minister to the downtrodden and marginalized.

And that last part, about caring for the downtrodden even in the face of death, is important. That, not binary gender roles or 1950s norms of respectability, is at the heart of the Christian faith.

Christianity in western Europe is no longer an imperial power; even with secular France restricting some religious practices, it is hardly an oppressed minority religion. Catholicism in particular wields considerable global power, and has, historically, often taken the side of the oppressor, especially in relation to Indigenous peoples, Jewish people, Muslims and LGBTQ+ people. And whenever it has done so, it has failed in its mission to live the Gospel of Jesus, who taught his followers to seek him in the least among us.

I don't believe that the Olympics ceremony organizers intended to mock Christianity any more than Serrano intended to mock Jesus. They may have intended to shock, but that's nothing new. Even pop art often shocks, and sometimes the shock is the point. Catholics who have spent time with the writings of Flannery O'Connor or Graham Greene ought to know this.

But let's say it was intended as mockery. Even then, why are we getting outraged simply because people don't respect us enough? Maybe we should consider the possibility that the church has not acted in such a way as to earn respect. Have we followed the Gospel and taken the side of truth and justice? Have we held the powerful among us accountable? Have we lived out a preferential option for the poor and vulnerable? If so, we should be confident in our faith and not be bothered by a little light mockery. And if we haven't lived out the Gospel — despite the power we wielded in Western civilization for centuries — demanding respect just looks like fragile entitlement.

Advertisement

This is not to say that everyone needs to like or enjoy or applaud the Olympic opening ceremony, "Dogma," "Piss Christ" or any other work of art that has challenged Christians to examine ourselves more closely. But if a photograph, story or performance is not to someone's taste they can opt to look elsewhere.

And if we need something to be outraged about, as Christians, the world offers us plentiful examples of real offenses against Jesus as present in the least among us. For instance, faith-based groups who are living out the Gospel mandate to aid refugees at the border have been attacked by hate groups. I'd like to see every Christian who got angry about the Olympic ceremony start showing the same level of outrage in response to that — especially considering how many of these refugee families are Christians themselves.

Sometimes Christians are the victims, sometimes the oppressors. Sometimes we are the helpers, sometimes the bystanders. Unfortunately, when it comes to our treatment of LGBTQ+ people, Christian culture on the whole has failed, even to the point of committing real sacrilege against Christ in the marginalized. With this in mind, maybe it's not the ceremony organizers who should be offering the apologies.