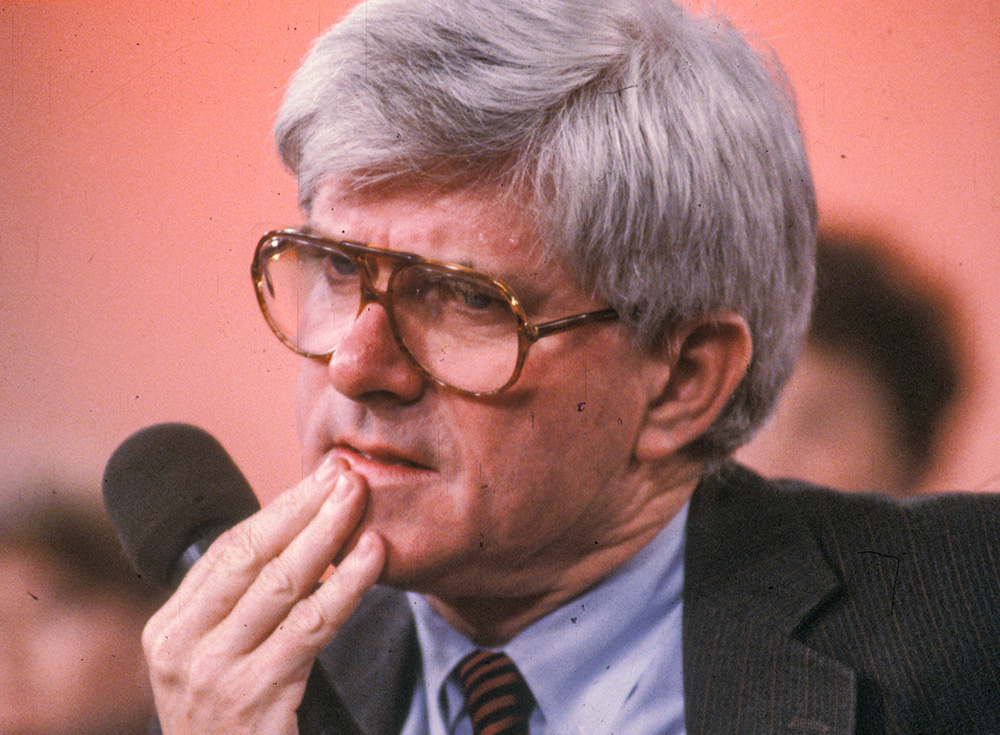

Phil Donahue listens on his television talk show in an undated photo. (Newscom/ZUMAPRESS.com/Al Stephenson)

Phil Donahue was to talk show hosts as Fr. Andrew Greeley was to priests and Jason Berry is to print journalists: the first in his field to credibly address the Catholic Church's then virtually unspoken problem of pedophile priests.

(At great risk, of course, the National Catholic Reporter was the first newspaper with a national circulation to write about abuses and cover-ups, before both Donahue and Greeley. The two men — and years later, many others — clearly read and were inspired by the NCR's seminal work exposing this corruption.)

The internet wasn't around back then and my memory isn't flawless, so it's possible that, technically speaking, other outlets may have discussed the abuse crisis even earlier than Donahue (perhaps an ultraconservative Wisconsin-based weekly called The Wanderer, for instance).

But none had anything like the reach and impact of "The Phil Donahue Show" (later shortened to just "Donahue").

For much of the 1970s and 1980s, Donahue, who died Aug. 18, 2024, at age 88, had the largest daytime audience in the country, attracting 9 million viewers every day.

In addition to his extraordinary reach, Donahue also enjoyed enviable credibility. On this topic in particular, his credibility was enhanced by the respectful way that he spoke about his Catholic upbringing and education at a private all-boys high school and the University of Notre Dame.

Advertisement

When Donahue, Greeley and Berry began digging into and discussing the abuse of kids by clerics in the 1980s, in fact, the crisis was nowhere near being called or considered a crisis. At best, the few who knew anything about the phenomenon considered child molesting clerics just a very few "bad apples" in an enormous barrel of selfless priests, nuns and bishops.

Unlike other similar shows, Donahue didn't report on a specific abuser or diocese. Instead he took the first in-depth examination of the scandal across the U.S. church. And he did so with remarkable sensitivity.

In 1988, his first show on the topic, Berry recalls, featured New Mexico psychiatrist Dr. Jay Feireman, who treated clergy offenders, reporter Carl Cannon, who had just done the first nationally syndicated series about pedophile priests for the Knight-Ridder chain, and Louisiana parents whose son had been sexually assaulted by notorious serial predator Fr. Gilbert Gauthe.

And on his second show about clergy abuse, Donahue described SNAP's mission and work, opening with a long segment respectfully and sensitively interviewing SNAP president and founder Barbara Blaine. (About our support groups, Donahue — with a slight but noticeable incredulity in his voice — said, "You are encouraging Catholics similarly situated, loved ones of Catholics, victims, parents, whatever it may be, to come together and you respect their privacy and you literally take over a hotel, not unlike a convention.")

His shows were very helpful to our small, struggling organization in three significant ways.

Back in the 1990s, nearly every victim we heard from — like each of us already in SNAP — felt incredibly isolated. Often even close friends and relatives couldn't believe our horrific experiences.

It was an extraordinary relief when a loved one did say, "I believe you. I'm so sorry." It was even more of a relief — and a nearly breathtaking validation — when that response came from a stranger, like a producer from "The Phil Donahue Show" and later from Donahue himself. It was a rare balm to our wounded hearts.

Our tiny group knew each other largely through long, late night phone calls when one depressed survivor called another for support. For the most part, we couldn't afford to gather in person.

But with "Donahue" and similar programs paying expenses, a handful of us were able to meet in person, building a deep foundation of trust and friendship that served us and our movement throughout the hopeless 1980s and 1990s, when all evidence suggested that our horrific experiences would never attract significant attention, much less bring any reform.

When, in 2002, the crisis erupted into broader public consciousness following The Boston Globe's investigation of Cardinal Bernard Law, SNAP leaders were prepared to seize the moment, help other victims to speak out, and respond well when reporters across the U.S. began calling for some perspective or a quote, an unintended benefit of having appeared on shows like "Donahue."

Secondly, Donahue went farther than most talk show hosts of the day, letting survivors identify on the air the names of their abusers and their often-corrupt church supervisors, while hosts and producers at other shows insisted in advance that victims avoid such specificity and bleeped out names later when victims forgot or disobeyed.

Even more surprisingly, Donahue also let victims expose the largely hidden hardball tactics bishops often used to intimidate survivors, witnesses and whistleblowers who dared to disclose abuse.

Berry, for instance, described a monsignor who prodded advertisers to boycott the small Louisiana newspaper that first ran his ground-breaking, well-documented stories about pedophile priests and their clergy enablers. (The boycott nearly succeeded.)

Ed Morris of Pennsylvania told of how the Philadelphia Archdiocese responded when he sued the cleric who abused him — by filing a countersuit against Eddie's parents. The archdiocese's stated rationale: If church officials were to be held accountable for Fr. Terrance Pinkowski's devastating crimes, so should Eddie's parents, since they willingly let the priest take their son on outings.

Mary Staggs of California named Fr. John Lenihan as her perpetrator, noting that even after he had admitted to his church supervisors that he had molested her, they kept him on the job in a parish.

Perhaps most important, talk shows like "Donahue" brought forth more victims than absolutely any other source. His producers put the SNAP phone number on the screen and hundreds would call seeking support.

In fact, shows like "Donahue" were so helpful that we in SNAP resolved to never turn down the opportunity to appear on one, regardless of how tawdry or exploitative they might seem. (As a result, for example, I was once on "The Jerry Springer Show," certainly one of the most sleazy. There was also a far lesser-known program on a small but national cable channel called "Am I Nuts?" We did that one too.)

SNAP had virtually no budget and the internet was years away. We'd tried but couldn't persuade even a single bishop to let us buy tiny ads in diocesan websites promoting our support groups. Without talk shows — especially "Donahue" and later "The Oprah Show" — we would have been able to reach and help far fewer survivors trapped in shame, silence and self-blame.

I can't speak to how Donahue handled other controversial and salacious topics. But with deep gratitude, I remember how compassionately he treated about a dozen abuse survivors long ago, back when so many considered us fabulists or kooks.

"He pioneered the coverage of a painful, complex topic with a notable restraint, not the carnival atmosphere on some of the shows," Berry remembers. "The guy had heart — a serious heart."