Demonstrators loot a burning truck after deadly protests to demand the resignation of Haitian President Jovenel Moise in Port-Au-Prince Nov. 19, 2019. (CNS/Reuters/Jeanty Junior Augustin)

"Something must change here."

If the Haitian Catholic Church were to pick a rallying cry, this surely would be a top contender. Famously proclaimed by Pope John Paul II during his 1983 visit to the country, the sentiment remains both a mantra and a call to action for Haitian clergy.

At the time of his visit, a decades-long dictatorship had damaged the country, thanks to the Duvalier family. Campaigns of terror created an environment of fear, instability and insecurity. When the pontiff landed in Port-au-Prince, it is safe to say he found a country that would either soon collapse under the weight of totalitarianism or rise in revolt to reclaim some semblance of freedom.

Decades later, the country is, once more, attempting to free itself from the ever-tightening grip of another would-be authoritarian ruler. A militarized police force, gangs rumored to be in cahoots with the government, an increasingly growing number of massacres in working-class communities, a chaotic school system and high-profile killings of journalists and a well-respected constitutional scholar once more threaten to push Haiti to the brink.

It is time for Pope Francis to draw attention to the suffering happening in Haiti.

The fascinating thing about wannabe strongmen rulers is that they rarely, if ever, behave in a way unique from others in their class. Since assuming the presidency in 2017, Jovenel Moise has behaved strikingly similar to U.S. President Donald Trump. Whether it's turning a blind eye to gang-led massacres in the struggling Bel-Air neighborhood, ignoring limits set by the Haitian constitution or making light of presidential term limits, Moise has shown that he has no desire to see Haiti through the democratizing process.

Advertisement

Yet, in his violent pursuit of enlarging the executive branch, Moise fails to contend with a resistance movement being led by activists, civil organization leaders and clergy.

Earlier this month, Andre Dumas of Nippes, Haiti, the president of the bishops' conference, revealed that a government official had approached him with a rather disturbing bribe: Quickly designate a church official to the president's Haitian electoral council and, in return, the government would allow bishops to appoint a person of their choosing to the Holy See.

This revelation came just weeks before Moise, bowing to pressure from the United States government, assembled an electoral commission made up mostly of unknowns who are now tasked with organizing legislative and presidential elections, and preparing a constitutional referendum — a move many legal scholars and human rights activists have deemed unconstitutional.

Several institutions that would usually be represented in the commission have refused to take part this go around as they believe, rightfully so, that an administration tied to stolen governmental funds, police brutality and emboldened gangs cannot oversee legitimate elections.

During the same sermon in which he revealed this bribe, Bishop Pierre-André Dumas said: "A lot of pressure is being placed on bishops, priests and nuns … for them not to speak the truth. It's as if everyone would like for the church to bathe in … lies."

And the bishop is not alone in feeling this way.

The government continues to crack down on dissent, using a militarized police force to attack peaceful protests and sending government officials with gunmen to the Court of Audits, one of the last, independent institutions in the country.

And just last month, the head of the Port-au-Prince Bar and noted constitutional scholar Monferrier Dorval was assassinated in the front yard of his home just hours after he called out the need for constitutional reform. The senseless killing galvanized not only Haitians at home and abroad, but the international legal community as bar associations across the world called for a full investigation into the matter.

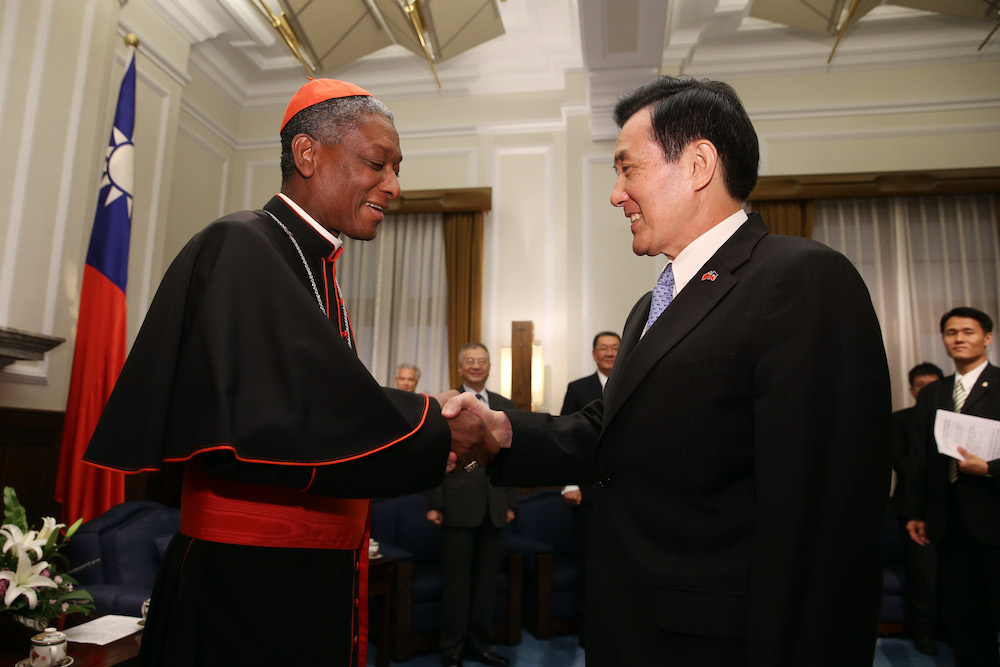

Taiwanese President Ma Ying-Jeou, right, greets Haiti's Cardinal Chibly Langlois, May 19, 2015. Langlois was in the country for the 90th anniversary of the founding of Fu Jen Catholic University. (Flickr/Taiwan Presidential Office)

This vile attempt to silence a key critic shows just how precarious and dire the situation has become. Even if the rest of the international community continues to prop up this administration, the Vatican should not fall in line with them. This would be a complete disregard of the fearlessness exhibited by the Haitian Church and the legacy of outspokenness set by John Paul II.

In an interview from 2018, the Francis argued that, "the Lord promises rest and liberation to all the oppressed in the world, but he needs us to make his promise effective." This promise cannot be carried out by those staring down a barrel alone. Those who are privileged enough to not have to live through the daily upheavals brought on by a strongman must also do their part.

Bishops, priests, nuns and the Protestant Federation must not be left to fend for themselves in the face of growing tyranny. Clergymen like Dumas have shown incredible courage in a time when fear is threatening to strangle so many others.

It is time for Francis to stand in solidarity with them. While the pope's 2014 appointment of the first Haitian Cardinal, Chibly Langlois, was heralded as a mark of the pontiff's reformist ideals for the country, Haiti needs more. Haitians need to hear the pope address the violence and insecurity head on. We must hear him denounce the corruption, the slaughtering of innocents, the negligence of children. We must hear him call for reform, call for a government with a conscience. Anything less would be a complete failure of responsibility to the millions of Haitians who call the Catholic Church their spiritual home.

[Valerie Jean-Charles is a communications strategist and editor of Woy Magazine, a Haitian news and cultural outlet. She lives in Washington, D.C.]