A person in a mask with lights spelling out at least the word "police" stands outside the site of the 2020 vice presidential debate between Vice President Mike Pence and Democratic vice presidential nominee Sen. Kamala Harris on the campus of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City Oct. 7. (CNS/Reuters/Jim Urquhart)

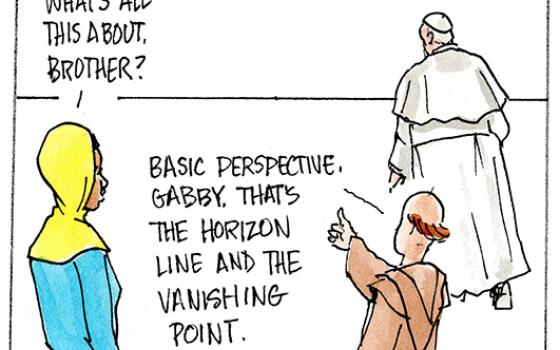

I love a good magic trick. Most of us do. I'm convinced it's the incongruities that charge our bodies with a sense of wonder: The jolt of confused pleasure we experience when our otherwise reliable senses have been fooled. That slack-jawed astonishment we feel as we try to make sense of witnessing a too-simple solution to a complex problem. There's a catch, though: Tricks take place on terms we find acceptable; otherwise, they're just lies.

"Defund the police" is a response to the lies conservative politicians in both parties have expertly tricked Americans into believing. These include, as Angela Davis warned decades ago, that policing and prisons could magically disappear our social problems and that the government cannot afford to pay for large social welfare programs.

This phrase is part of a long abolitionist tradition in the United States, but it resonates with a wider audience today because two truths have exposed the barbarism endemic to American capitalism: First, that not even a once-in-a-century pandemic can slow police violence. Second, that our government is so unaccustomed to providing for us that it tries, and keeps failing, to create a last-minute social safety net through emergency legislation.

America's catastrophic responses to the coronavirus pandemic and to racial justice protests have made plain for many the effects of a 40-year project that began in the early 1980s. At the time, Ronald Reagan campaigned on both cutting social programs and doubling military spending. Contemporaries understood Reagan's cuts as the formal end of half a century of large-scale government poverty interventions spanning the New Deal and the Great Society. Cuts were so steep that workers earning as little as $6,500 a year — less than $19,000 today — were kicked off welfare rolls.

Advertisement

As leaders siphoned funds from agencies that promote human flourishing, they redirected them to policing, prisons and militarism. While problems such as homelessness, poverty and substance abuse have all intensified this year, police and prisons are the sectors of government most primed to "solve" them today.

Abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls this sleight of hand "organized abandonment of vulnerable communities." It is characterized by the privatization of public goods and services, divestment from social welfare, and investment in institutions of state violence. In this view, the pandemic and police violence are twin problems rather than unrelated events whose coincidence we can attribute to 2020. Juxtaposed images of nurses wearing garbage bags for scrubs while police suppress protests in cutting edge gear illustrate this.

The moral stupidity that produces these outcomes cannot be blamed solely on the current occupant of the White House. Donald Trump's ascension to the highest office is at once a symptom and a cause of our decay. He did not erect history's largest prison system. Military expenditures were already our largest federal discretionary expense when he took office. These failings are his — and our — inheritance.

Reagan's culture war on the urban poor — whom he framed as drug-addled, pathologically violent welfare cheats — exacerbated dehumanizing perceptions of how every level of government should relate to that population. This culminated in his Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. The $1.7 billion legislation allocated $500 million to further militarize the country's anti-trafficking efforts through the Coast Guard, Customs and the DEA. It provided over $322 million for surveillance technology. In a sign of things to come, the bill also sponsored a Pentagon-led study of the feasibility of converting surplus federal buildings into prisons.

In 1996, Bill Clinton declared in his state of the union address that "the era of big government is over." He, like Reagan, didn't mean "big government" per se, but social services. The proclamation was a victory cry after Democrats, in close collaboration with House Republicans, further gutted the welfare system with the passage of the controversial Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act.

Washington Auxiliary Bishop Roy E. Campbell and a woman religious walk with others toward the National Museum of African American History and Culture during a peaceful protest June 8, following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police May 25. (CNS/Bob Roller)

Conversely, policing and prisons had already expanded thanks to Clinton's 1994 crime bill. Rather than funding programs to alleviate the recession-level 10.6% Black unemployment rate, the $30.2 billion bill allocated $9.7 billion for new prison construction, and $10.8 billion for things such as putting an additional 100,000 police officers on the streets. The bill's programs were funded by cutting 270,000 jobs from elsewhere in the federal government per the recommendation of Vice President Al Gore's National Performance Review. The administration haphazardly downsized many frontline positions, according to the Government Accountability Office, causing lengthy backlogs in service-oriented agencies such as the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Magician Penn Jillette identifies something illuminating, if not unsatisfying, as the problem with giving away magicians' secrets. "You can't give away real magic tricks. And the reason is they're too boring. It's hard work," he says. "You'd be dozing off halfway through." Once we agree to be tricked, our delight rests in not knowing how it happens, only that it does. We are complicit in our own deception. Desire and consent spawn the ignorance needed for audiences to co-create magic with magicians.

The pandemic and the protests have made such ignorance impossible.

Our 40-year project has made us the global leader in incarceration. The socioeconomic problems police and prisons "solve" have heightened during the pandemic. Eight million renters face eviction and homelessness. Overdose deaths, a national plague that claimed 70,980 lives in 2019, appear to be up more than 17%. Eight million Americans have been driven into poverty since May.

The pandemic, like policing and prison, has not exacted an equal toll. Both continue to disproportionately ravage the communities of Black and brown people, as well as poor whites.

As people of faith, we must use our highest values to navigate this crisis. Here the Catholic Church's option for the poor can be our lodestar. The only way to make it out with these newly vulnerable people intact is to demand that our elected officials once again radically redistribute public funds. This time, they must move resources away from violent institutions and toward meeting human needs. After all that we have lost in this pandemic — and all that we will lose — we cannot afford to disappear another generation of so-called "problems" behind prison walls.

Those problems are people.

[Dwayne David Paul is the director of the Collaborative Center for Justice, a Catholic social justice organization sponsored by six communities of women religious.]