Demonstrators in Washington, D.C., gather along the fence surrounding Lafayette Park outside the White House June 2. (CNS/Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)

To breathe or to take a breath is the clearest sign of life. In my previous ministry as a hospital chaplain, I had the privilege of appreciating more deeply the importance of breathing. It is literally a matter of life and death. When someone begins to struggle to breathe, it signals that he or she is being dragged from the space of life into the arms of death.

It is a painful struggle to watch, sometimes helplessly. In the hospital setting where I worked, such experiences happened with dignity, care, and love for the patient. Think of how the importance of breathing has become accentuated by the desperate need for ventilators and respirators in the fight against COVID-19.

By faith we know that God's breath is the origin of life. We literally draw our first breath from God. We are quickened to life by God's breath. To breathe is a gift from God; it is an experience of the life of God within us.

The experience of breathing has occupied my mind these days as I think, reflect and pray about the murder of George Floyd — an unarmed African American man who was suffocated to death. A police officer planted his knee firmly on George's neck to the point where he couldn't breathe. His pleas to be allowed to breathe fell on deaf ears. Life was snuffed out of him.

In my reflection, I ask what breathing means to me as a woman of Nigerian and African origin living and working in America, especially under these circumstances. The answer epitomizes my own perennial journey of struggling to reconcile my dual identity as a Nigerian-American.

Advertisement

Bringing these two realities together feels like trying to activate my two lungs to function efficiently. It is a daunting task in a country like America. Sometimes the experience is joyful and fulfilling; most times, it is painful and stressful. I have never been able to breathe fully and truly out of both lungs of my dual identity. It is a constant struggle as I navigate the contours of my identity as an African in America.

I came to the United States over two decades ago. Prior to coming to America, I had not the slightest clue what racism meant outside of its dictionary definition and grammatical use, even though colonial African literature is replete with experiences of racism. But I was born after my country of origin, Nigeria, gained independence from Britain.

Nigeria counts over 250 languages and ethnic groupings. This diversity has its merits and demerits. On rare occasions, it coalesces into a harmonious configuration with a purpose and an intent that generate a space where each citizen feels valued, respected and has a sense of belonging.

Other times, most times, the diversity degenerates into atavistic tribal affinities and conflicts that define and exclude — and sometimes eliminate — the other as a threat. This could be for flimsy reasons — different dialects, sartorial preferences, or cultural practices. We call it tribalism. And it is always important to call it out.

Whenever it rears its ugly head, we call it by its name, because we know that it is not life-giving. Tribalism is the antithesis of life. Yet, looking back on my adult life in Nigeria, I realize that there was a unique and constitutive component of our identity: all of us without exception were black. We still are. You couldn't be more or less black. Being black was not a marker of difference. We embraced it as a fundamental and unalterable identity. This identity neither conferred privilege nor justified discrimination. You are black and that's that.

When some white people shunt past me in a line, their excuse always baffles me: "Sorry, I didn't see you." How could someone be so black and still be so invisible in broad daylight?

Today, I live in America, a country where being black means and makes a difference. It is a painful realization that I have struggled with for over 20 years since coming to America. Not only is it painful; it is a suffocating experience.

Consider this. Even though I am an American citizen, I still can't breathe when filling out a form that forces me to identify my race as a black — or simply "other." I can't breathe when I have to constantly fight to be seen or recognized as a human person. Actually, when some white people shunt past me in a line, their excuse always baffles me: "Sorry, I didn't see you."

How could someone be so black and still be so invisible in broad daylight? How could someone officially designated as a person of color lose her luster to a racist-tainted myopia?

I can't breathe, when I am disregarded and considered less than another person solely on account of the color of my skin.

As a Nigerian-American, I can't breathe when my name is judged too complicated and better off "Americanized" so it can be pronounced. I can't breathe when I have to scream to be heard and taken into consideration. Every struggle to belong, to be heard and to be seen takes an incredible amount of energy. It drains me of life; it deprives me of breath. It is tough going.

No ordinary breath

We all can recall a time in our lives when we felt stifled, unable to breathe and drained of life. Jesus of Nazareth found himself on the cross, struggling to breathe, until he couldn't anymore and had to give up: "It's finished," he said.

Jesus knew what it meant to be denied the breath of life. And as soon as he was raised from the dead by the power of the Spirit of God, he seemed determined to right that wrong. One of his first deeds was to breathe on the disciples, saying "Receive the Holy Spirit."

He didn't want his followers to suffer the pain of not being able to breathe. He restored God's original gift to humanity: He gave us a breath of life. In so doing, he fulfilled his core mission on Earth: "I have come that all people may have life and have it in all its fullness" (John 10:10).

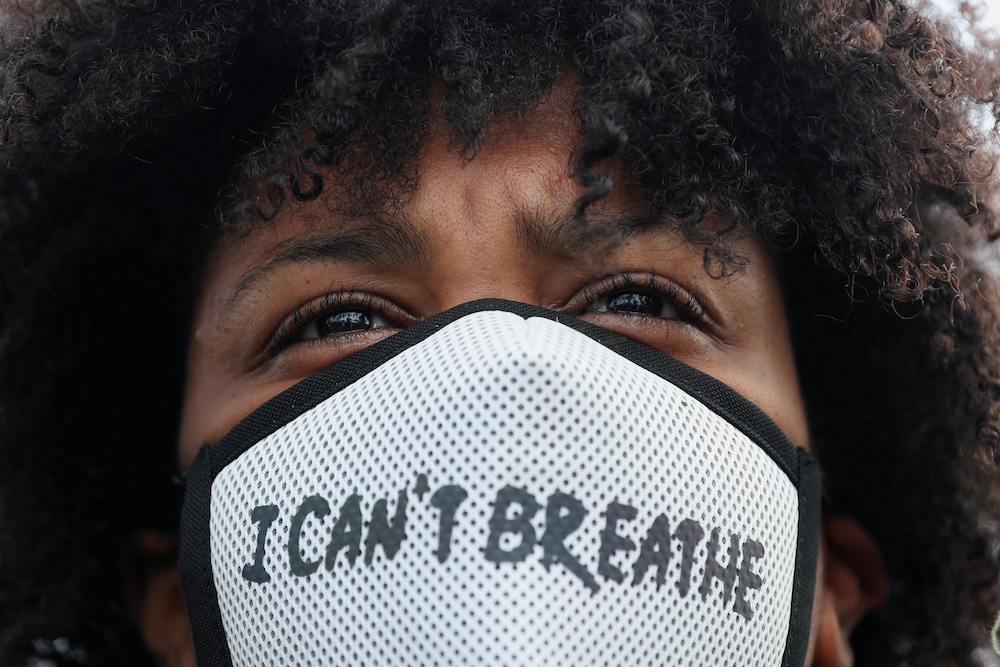

A demonstrator wearing a protective mask takes part in a protest in Rotterdam, Netherlands, June 3, following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota. (CNS/Reuters/Eva Plevier)

In its new post-resurrection form, this breath is personalized as the Spirit of God. It is no ordinary breath. It blows wherever it wills untrammeled by the forces of racism, discrimination and prejudice.

As a woman, I have found solace and comfort in embracing the reality of the Spirit as the powerful life-giving feminine expression of God. In my struggle to bring my two identities together, to breathe with two lungs, in America, I hear this same Spirit filling me with life, saying: "Breathe, Anne. Breathe free. Breathe life. Receive my Spirit."

Breathing in and breathing out is a sacred gift of God, given to all of creation without consideration of class, status, or estate — much less race. Connected with this gift are the gifts of freedom and dignity. To assault any of these is to deny life to a person — as George Floyd and so many others have been denied life.

I was deeply pained and outraged as I witnessed the choking off of George Floyd's breath. I still am. I can't imagine his pain and suffering in that final moment. There he was, his neck under the merciless knee of a fellow man who wore a smirk on his face, while breathing in and breathing out, even as he choked a defenseless, helpless man to death.

This act offends God, and so does every unjust system and structure that has allowed some people to feel more entitled to draw life-giving breath, even as they deny others that same right. My heart joins and bleeds with all those who can't breathe in America and elsewhere in the world.

So many of my sisters and brothers find it difficult to even take a breath. Black men in America, immigrants from other shores, black and poor women in America; people with disabilities, the elderly, the Native peoples, gays and lesbians, Hispanic and Asians — in short, all those who are considered other and, therefore, lesser.

Even nature and Mother Earth cannot breathe when we pollute them and disregard them. In so many ways, all of creation is groaning and crying out: "I can't breathe!"

As the protests continue, I see people on the streets — breathing in and breathing out. In their voices I hear the God of life screaming and asking for space to breathe again. All desiring to breathe — citizens and law enforcement agents, politicians and partisans.

Meanwhile, in hospitals and nursing homes, people sickened by COVID-19 struggle to breathe on ventilators and respirators. To breathe is to live. One of the vital revelations of George Floyd's killing is that racism deprives people of their right to breathe, that is, their right to life.

If this land is what it claims to be — of the free and of the brave — racism should no longer be allowed a place in our lives, institutions and communities. We need to be able to breathe with both lungs no matter the color of our skin. Let's take a breath. It is our God-given right.

[Social Service Sr. Anne Arabome is the associate director of the Faber Center for Ignatian Spirituality at Marquette University.]