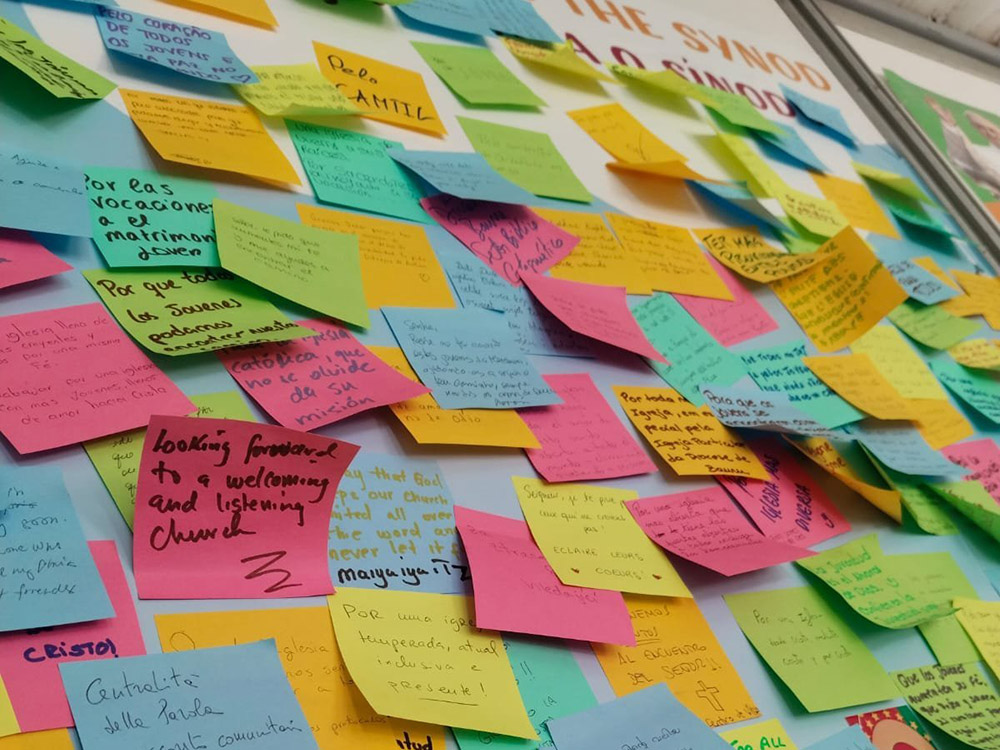

Dozens of Post-it Notes with prayers and requests from young people are seen on the wall at the Synod of Bishops' booth in a park in Lisbon, Portugal, during World Youth Day Aug. 1-6. (OSV News/Courtesy of the Synod Secretariat)

In October, the Catholic Church is going to have an international meeting in Rome on the topic of synodality. This is an unfamiliar term to most Catholics, except those of Eastern traditions, whose bishops regularly come together in synods to govern the church. In the Western church, we call such meetings "councils," not synods.

What then is synodality?

My own unsophisticated understanding is that it is another word for "collegiality," a term that became popular after the Second Vatican Council in the early 1960s.

At the council, bishops became conscious of their collegial responsibility with the pope for the governance of the church. It was wrong, they realized, to view the church as an absolute monarchy with bishops as vassals of the pope. The college of bishops, as successors of the apostles, has an important role to play.

After the council, the term "collegial" became an adjective describing a new style of church leadership that envisioned consulting the laity on important issues facing the church. It was applied to not only bishops and their conferences, but dioceses and parishes.

This widespread use of collegiality soon came under attack from the Vatican, with then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) leading the charge. He insisted that collegiality in the strict sense applied only to the college of bishops under the pope. He made distinctions between "affective" and "effective" collegiality — the former saw bishops' meetings as little more than mutual support; the latter considered them authoritative.

By the time the Vatican was done, collegiality became a dirty word tied up in so many distinctions that it eventually fell out of use.

Synodality, then, might be thought of as collegiality resurrected, but without all the baggage that encumbers collegiality. The difference is literally semantic: Synod has a Greek root, collegial a Latin root.

If Pope Francis had announced a synod on collegiality, it would have immediately bogged down in all the old controversies over collegiality and quickly turned into a debate over Benedict's versus Francis' views. By choosing another word, synodality, Francis sidestepped this sterile debate so we could deal afresh with the question of how we want to be church.

But synodality goes beyond collegiality as a practical vision for the church. The instrumentum laboris ("working paper") prepared for the synod delegates describes synodality not as a theory but as "a readiness to enter into a dynamic of constructive, respectful and prayerful speaking, listening and dialogue."

"At the root of this process," explains the document, "is the acceptance, both personal and communal, of something that is both a gift and a challenge: to be a Church of sisters and brothers in Christ who listen to one another and who, in so doing, are gradually transformed by the Spirit."

Advertisement

The working paper says, "A synodal Church is founded on the recognition of a common dignity deriving from Baptism, which makes all who receive it sons and daughters of God, members of the family of God, and therefore brothers and sisters in Christ, inhabited by the one Spirit and sent to fulfil a common mission."

A synodal church provides "space in which common baptismal dignity and co-responsibility for mission are not only affirmed, but exercised, and practiced." In this space, the exercise of authority in the church is seen as service, "following the model of Jesus, who stooped to wash the feet of his disciples."

A synodal church is therefore a listening church on a synodal journey that involves "listening to the Spirit through listening to the Word and listening to each other as individuals and among ecclesial communities, from the local level to the continental and universal levels."

The instrumentum laboris goes on to say that a synodal church "desires to be humble, and knows that it must ask forgiveness and has much to learn."

A synodal church is a church of encounter and dialogue. It is not afraid of the variety of Catholic ideas and people, but values it, without forcing them into uniformity. A synodal church is open, welcoming and embraces all. It can manage tensions without being crushed by them. It has a sense of incompleteness and a healthy restlessness.

Ultimately, a synodal church is a church of discernment where "we listen attentively to each other's lived experiences, we grow in mutual respect and begin to discern the movements of God's Spirit in the lives of others and in our own."

The goal is to pay more attention to "what the Spirit is saying to the Churches," the document says, quoting the Book of Revelation, in the commitment and hope of becoming "a church increasingly capable of making prophetic decisions that are the fruit of the Spirit's guidance."

The shift to synodality from collegiality is no sure answer to critics of Francis who want to get the church bogged down in a debate over synodality just as it was over collegiality. Francis refuses to engage in this debate.

He wants to do synodality, not debate ecclesiology. He wants us to be church, the community of the disciples of Christ listening to the Spirit and continuing Christ's mission in the world.