A bilingual voting sign is seen at St. Patrick Church polling station in Norcross, Ga., on Election Day 2020. (OSV News/The Georgia Bulletin/Michael Alexander)

Much ink has been spilled recently on the Catholic vote, shifts across election cycles and the ways subpopulations of Catholics voted. As important as elections are, it's critical that leaders and other reflective Catholics pause and consider how these votes are rooted (or not) in broader Catholic principles.

My co-authors and I have learned a great deal about Catholicism in American public life through our national survey of more than 1,500 Catholics and interviews with nearly 60 Catholic leaders. The findings, elaborated in Catholicism at a Crossroads: The Present and Future of America's Largest Church (NYU Press, 2025), have much relevance as Catholics — especially Catholic leaders — seek to better integrate faith and politics in a way that leads to a more thriving church and nation.

I am frequently asked whether Catholicism impacts the political attitudes of the faithful. The answer is complicated.

Some signs point to no. Our survey asked Catholics whether their faith impacted the way they voted in their last presidential election; only 10% said it did. A full 86% said their religious beliefs played no role in their decision. From this perspective, it looks like Catholics vote more according to their party than their faith.

But other signs point to yes. When we ask whether the bishops' stances impact their political attitudes, nearly two-thirds (64%) say yes. Breaking this down into a bit more detail, 9% say they try to follow the bishops' guidance and instructions on political and public policy matters, and 55% say they consider the bishops' positions, but ultimately make up their own mind (36% say the bishops' views are irrelevant to their own political commitments).

We wondered whether the depth of Catholic commitment affects the ways Catholics think about political issues. Excitingly, the answer is a resounding yes.

Yet even though respondents claim that the church influences their thinking, the Pew Research Center found otherwise, reporting that, with few exceptions, there is very little difference among Catholic Democrats and Catholic Republicans when respectively compared to Democrats and Republicans as a whole. Ultimately, it seems, Catholics' opinions are formed with a "party-before-faith" approach.

Given all this, we wondered whether the depth of Catholic commitment — measured by self-reported Mass attendance, likelihood of leaving Catholicism and the importance of Catholicism in one's life — affects the ways Catholics think about political issues. Excitingly, the answer is a resounding yes.

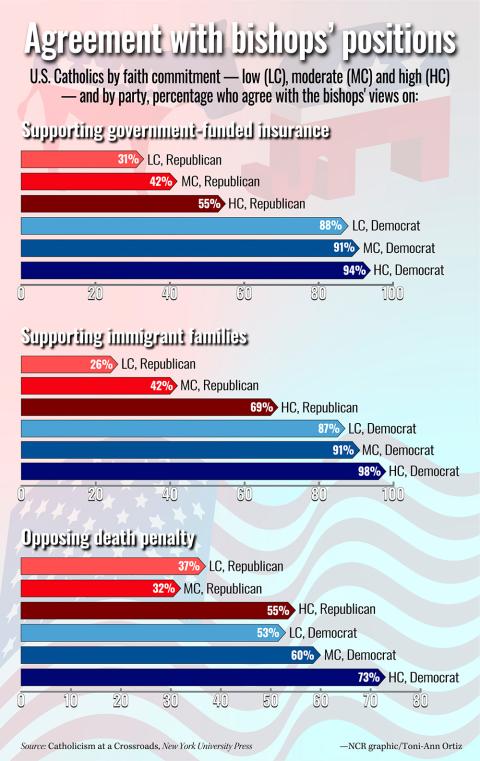

When we explored the ways low-, moderate- and high-commitment Catholics of both parties think about issues, it was clear that the more committed respondents were to their faith, the more likely they were to depart from their party's platform and agree with the church's teaching.

The accompanying graphic shows three questions that ask about Catholic concerns that align with the Democrats' policies. We see that there is a strong tendency for Republicans who are high-commitment Catholics to disagree with their party, most strongly so on the immigration issue.

The next set of questions asked whether one can be a good Catholic without following the church's teaching on abortion or same-sex relationships, or without giving time or money to help the poor. Across the board, highly committed Catholics exceed the low- and moderate-commitment levels of the opposite party. High Catholic commitment reverses the dominant trend, with these Catholics taking a "faith-before-party" approach to their politics.

This nuance paints a more hopeful picture of Catholic political involvement and illuminates ways to better integrate faith and political involvement. Highly committed Catholics — who are about 20% of the total survey sample — have much in common with one another, and are far more unified than low- and moderate-commitment Catholics. High-commitment Catholics are already grounding their politics in their faith and can help lead the church in a less partisan approach to public life.

In talking to some key leaders in this area, four themes emerged in our conversations about a more robustly Catholic response to American public life. They claimed our Catholic discourse needs to amplify 1) solidarity and 2) the common good. We also need to 3) expand Catholics' imagination, and 4) form ourselves through a culture of encounter.

John Carr, founder of the Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life at Georgetown University, challenges the ways voters typically choose a candidate and provides an alternative that is rooted in solidarity: "The question, 'Am I better off than I was four years ago?' That's not the question. Instead the questions are, 'Are the poor better off? Are the unborn protected? Are immigrants welcome? Is human dignity being lifted up?' "

Insofar as we think about the ways human persons are connected to one another and allow the sufferings of another to become our own sufferings, we ground our political mindset in solidarity.

Advertisement

Stephen Schneck enjoyed a lengthy career at the intersection of politics and Catholicism, including founding the Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies at the Catholic University of America. He amplifies the importance of the common good in a Catholic response to public life: "Citizenship for us Catholics should really revolve around our recognition that the common good should be primary. And our private interests — whether those private interests are partisan or business interests and so forth — that those things should be secondary."

Further, keeping the common good primary allows us to see the ways our personal good is wrapped up in the common good.

We also need to help one another to see the world with a more expanded imagination. Kerry Robinson, president of Catholic Charities USA, suggests, "I do believe that one's faith — if it is a mature, adult faith — informs all that one does. It's not something you just add on, but it really does ground you into a certain understanding of responsibility to the common good — to one another, to our common home — out of a love of being loved by God."

A mature faith that is grounded in love and foundational to a person helps them to see the whole of their world first and foremost from a perspective of faith.

Finally, a culture of encounter will help Catholics get to a place where we can put partisan claims aside and discover the importance of becoming our brothers' and sisters' keepers, as explained by Bishop John Stowe of Lexington, Kentucky: "I think on the immigration case, I think the strategy that has been employed for some time now ... is to put a human face on stories of migrants and refugees. It's one thing to have a position on the category of migrants. It's another thing to engage with migrant families or at least to know their stories."

Truly encountering others helps to humanize statistics and abstract social problems.

These findings should spark ideas for parishes, dioceses, lay apostolates, high schools and more. With a wise use of these four tools from our tradition, we can begin to better integrate our faith with our politics, as well as our personal and social lives more broadly.