Civil rights leader the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. smiles during a talk with U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson, not pictured, in this undated photo. The federal holiday that celebrates the iconic civil rights leader is observed Jan. 18. (CNS/Yoichi Okamoto, courtesy of LBJ Library)

When the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. launched the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955, I was a 10-year-old boy living in an all-white Brooklyn neighborhood. Except when my parents took me on the subway, I never saw a Black person. I had heard of King, but he wasn't part of my narrow world. Then, in 1958, my father was transferred to New Orleans — and that world changed overnight.

In 1957 King had co-founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in an attempt to spread the struggle for racial justice throughout the South, thereby accelerating racial tensions in states like Louisiana that by law were segregated. This was the world I entered when my plane landed in New Orleans. It was the first time I had been outside the New York/New Jersey area, and "White" and "Colored" signs on restrooms and water fountains, along with picketers calling for desegregated lunch counters, made me feel uncomfortable.

Since my mother and siblings could not join us immediately, my dad and I stayed in a hotel and found time to explore our new city. I was delighted when he took me to my first Mardi Gras parade. We found ourselves enveloped by a crowd excitedly attempting to catch beads thrown by masked revelers from countless passing floats. This was exotic compared to Brooklyn, and I immersed myself in the merriment.

But before long a white man and a Black boy standing nearby simultaneously grabbed a cheap strand of beads and began tussling over it. Suddenly a policeman smashed his billy club on the boy's head. I could see the pupils of his still-opened eyes rise into his forehead, a memory that still haunts me. After the policeman dragged his victim away, the crowd — including the white adult involved in the scuffle — returned to catching trinkets as if nothing had happened. On that day, I got my first inkling of what Dr. King was fighting for.

The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

When the rest of my family arrived, we moved to suburban Kenner. Since there was no Catholic high school nearby, my parents enrolled me in a Catholic school in New Orleans, even though this meant a round trip by bus requiring an hour each way. Although the buses were by now legally integrated, almost all white riders stood rather than sit by a Black person.

One day, as I boarded a crowded bus, I took a seat next to a Black man. It was then that I learned how insidious the racial culture of the South really was: Fellow passengers began taunting my seat companion. Not one word was aimed at me, even though I had initiated the flouting of southern norms.

For the rest of that school year I stood rather than sit by someone Black. I simply couldn't chance causing a fellow human being to be mocked and insulted.

Towards the end of my freshman year, each pupil in my speech class had to compose a persuasive speech on a topic of his choice and present it before his classmates for critique. One student claimed in his speech that King and his associates were undermining "our southern way of life," yet white kids finance such efforts when they bought records by Black singers. He concluded by calling for a boycott of Black recording artists.

When no other student — nor our teacher, a Christian Brother — questioned the moral appropriateness of this speech, I felt an impulse to do so. But fearing a negative reaction from my classmates, I remained mute and ashamed of myself.

Advertisement

Following my junior year, I transferred to another Catholic school and was desperately trying to fit in. In religion class a student commented that his father read that Cardinal Richard Cushing of Boston belonged to the NAACP. When he questioned this since the NAACP was a "communist organization," our teacher, a nun, suggested that his father must have been mistaken.

Shocked at her inadequate reply, my instinct was to set the record straight. Then, like two years earlier in speech class, I hesitated, fearing my classmates' scorn. But this time I braced myself and spoke: "The NAACP is an organization fighting for justice for Black people. It isn't communist." Another student, a Cuban refugee, added that as someone whose family had fled communism, he was saddened to see how unjustly Blacks were treated in what his family had believed was "the land of the free." Neither of us was ridiculed and I was proud of speaking out. In my adolescent self-satisfaction, I was sure that if King had been there that day, he would also have been proud of me.

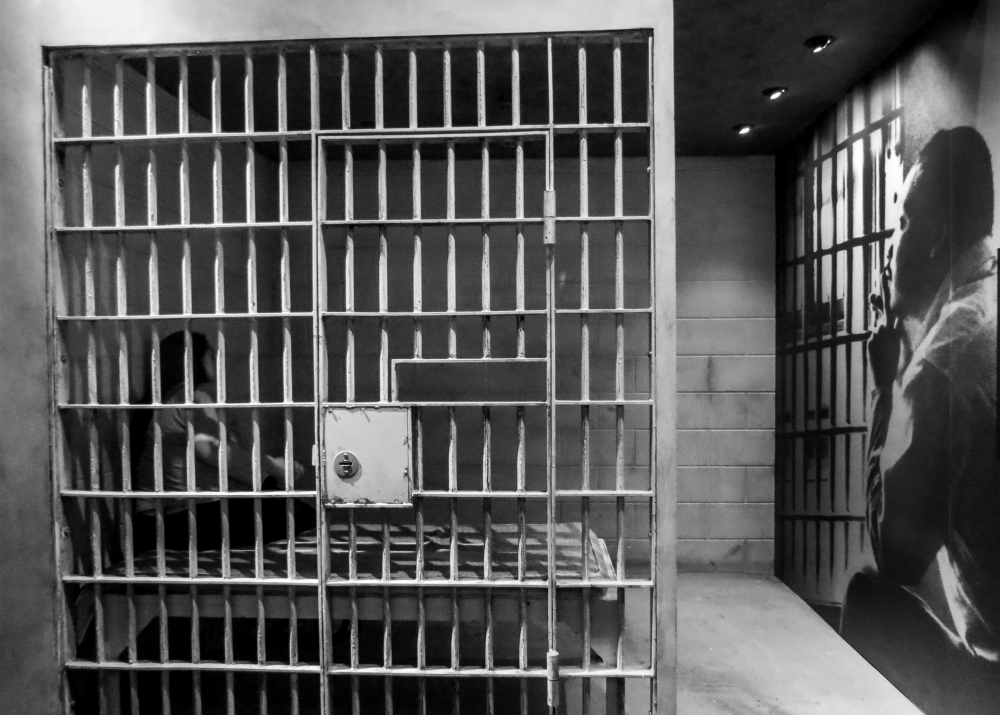

In 1963, King faced his toughest challenge yet when police in Birmingham, Alabama, viciously attacked Black protesters — some no older than I. Arrested and jailed, King was deeply distraught when eight of the city's leading clergymen, including a Catholic bishop, penned a letter to the editor of The Birmingham News, contending that questions of civil rights should be determined in the courtroom and not by "outside agitators" in the streets. King felt he must challenge their statement: His ensuing "Letter from a Birmingham Jail" is a brilliant apologia that is still read around the world.

A visitor sits in a replica of a jail cell next to a portrait of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., in 2015 at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee. (CNS/EPA/Tannen Maury)

I didn't read King's letter until many years later, but when I did it helped put into perspective a troubling issue in my own religious life. Among the many points made by King, what struck me most was his revelation that when he began the Montgomery bus boycott, he naively thought that white pastors would support him, since the Gospels emphatically call for justice for the marginalized. Instead, some were openly hostile, while more "remained silent behind the … security of stained glass windows."

This last phrase deeply affected me. I have often encountered bishops and priests (seldom nuns) in my own faith who employ the term "prudential judgment" to rationalize avoiding controversial justice issues. I wondered if "prudential judgment" was simply a convenient term to rationalize moral cowardice — now King's comment told me that my cynicism was justified.

Yet, it is also clear from King's "Letter" that he would not let others' failings dampen the hope he found in the prophetic message of the Gospels. Indeed, King's unmitigated hope has often bolstered my own spirits when just causes seem hopeless to me.

Although many church leaders have fallen short when it comes to prophetic witness, others have not. Nowhere was this more apparent than in Selma, Alabama, in 1965. Following the vicious beating of peaceful protesters by police on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, King called for people of goodwill to come to Selma to join in a subsequent march. Hundreds responded, including large numbers of church people willing to risk their lives.

For Catholics in particular, Selma represented a moment of remarkable change. Church leaders had long felt it was unseemly — indeed, scandalous — for priests and nuns to take part in political protests. But after Selma such thinking lost sway and it became standard fare to see religious sisters and Catholic clergy marching for justice. This was a watershed change — due in part to King's clarion call.

2015 marked the 50th anniversary of the Selma march. My wife and I decided to drive there and retrace the path taken by King and his fellow civil rights heroes. Walking across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, we were moved to tears, but what touched me more was the prominent display we encountered upon entering a museum just outside Selma. Greeting us was a cluster of life-sized statues depicting those who had marched in the front lines with King. And just behind the civil rights icon was a young Black nun in full habit.

I knew immediately that she was Sr. Antona Ebo, since I had met and talked with her not long before. I stood in awe before her statue, thinking of the courage she displayed those 50 years ago. At that moment I felt proud to be Catholic.

After leading the 1966 march for fair housing in Cicero, Illinois, King said that the resulting violence surpassed anything he had seen, "even in Mississippi and Alabama." I then realized that racial hatred was not confined to the former Confederacy. The next year he condemned the Vietnam War, risking the wrath of many white civil rights allies, while teaching another valuable lesson: It is immoral to demand justice for one's own people, while ignoring injustice towards others.

After receiving my doctorate in 1979, I embarked on a four-decade career as a historian. Although I have written on topics dealing with Black people, my primary focus has been on missioners murdered in Central America, because they supported the marginalized in their struggle for dignity. When I first began this research, I was surprised to find bishops who castigated these martyrs or remained silent when they were killed. I recalled King's "Letter from a Birmingham Jail" and, sadly, put their conduct in historical perspective.

In recent years, as we witnessed President Donald Trump stoke the flames of the latest reincarnation of racial bigotry, King's words again ring true. Asked in 1965 about racist remarks made by Gov. George Wallace, King noted: "I am not sure that he believes all the poison that he preaches, but he is artful enough to convince others that he does."

The same could be said for Trump. But lest we despair, King reminds us that "the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice" — as long as we don't give up the struggle.

[Edward T. Brett is professor emeritus at La Roche University in Pittsburgh. He is the author or co-author of five books, including Murdered in Central America: The Stories of Eleven U.S. Missionaries, Martyrs of Hope: Seven U.S. Missioners in Central America and The New Orleans Sisters of the Holy Family: African American Missionaries to the Garifuna of Belize.]