A monstrance containing the Blessed Sacrament is displayed on the altar during a Holy Hour at St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York City July 13, during the ongoing National Eucharistic Revival. (OSV News/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Scrawled on barrio walls, displayed on church banners, spray-painted on buses, you can still read his promise: "If they kill me, I will rise again in the struggle of the Salvadoran people." These are the defiant, Gospel-driven words of Archbishop Óscar Romero, shortly before he was struck down by an assassin's bullet on March 24, 1980.

Romero was killed while celebrating the Eucharist. While some view this as a mere "accident of history," the Salvadoran people see this as far more than a coincidence. It is rich in sacramental symbolism and implicates us — all of us — in an unswerving call to discipleship. Romero's death literally embodies Jesus' words: This is my body, broken. This is my blood, poured out. Do this in memory of me.

Thousands of the oppressed people of El Salvador united their broken bodies and outpoured blood to Christ's memory during the brutal civil war that followed (1980-92). They kept the promise. They lived the memory, not only by their faith in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, but also — and perhaps especially — in the real presence of the body of Christ in his campesinos, in the lucha (struggle) of the Salvadoran people.

Hearing the echo of their beloved Monseñor Romero, they incarnated the mandate of God's faithful son and servant. They bore the mark of the cross, the living memory of Jesus in their lives.

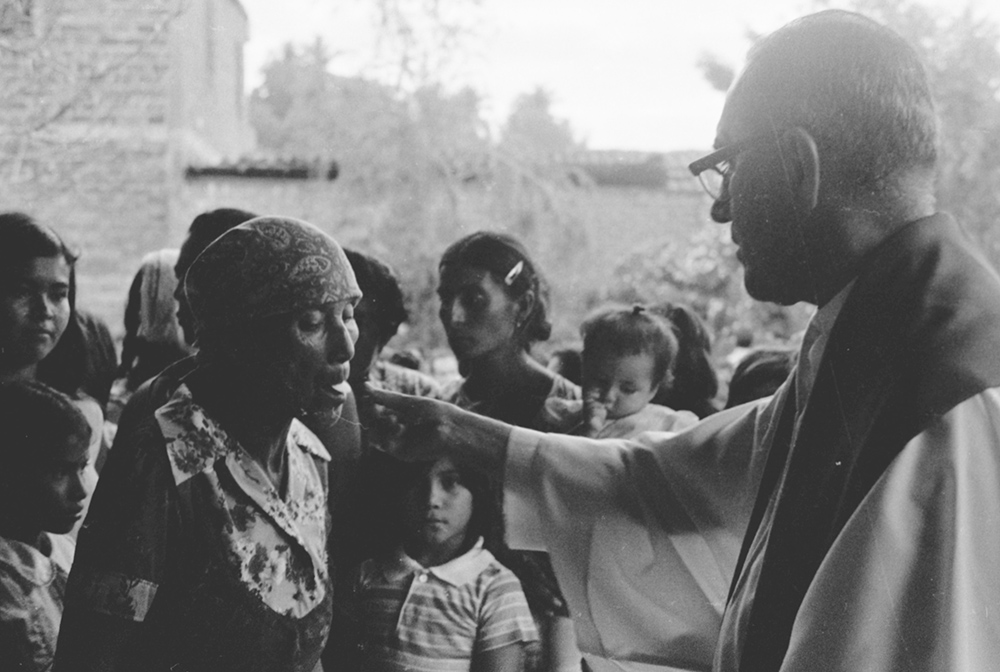

Archbishop Óscar Romero offers Communion to a woman during a confirmation Mass in Ateos, El Salvador, in September 1979. (NCR photo/June Carolyn Erlick)

Like the people of El Salvador, we too are called to bear witness to this inseparable bond between the Eucharist and gospel nonviolence. Nonviolent, suffering love is the living breath, the pledge that unites the Last Supper to the cross. It is the beating heart of the Eucharist.

But this leaves us with a disturbing question. What happened to Jesus' clear moral demand that we — like Peter — are called to put away our sword, not just personally, but in all its systemic cruelty: climate destruction, poverty, racism, xenophobia, misogyny and unjustifiable "just wars"? Where is this spirituality of the Eucharist as the sacrament of nonviolence today?

Regrettably, this core conviction is largely absent in the U.S. bishops' three-year plan of eucharistic revival, which concludes next summer with the 10th National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis. So far, the bishops are focused on urging post-COVID Catholics to come back to church and to renew their belief in the real presence of Christ in holy Communion and the reserved sacrament.

To be clear, I respect this concern. I grew up in the Catholic culture of pre-Vatican II, spiritually formed by the Latin Mass, Benediction, Forty Hours, visits to the Blessed Sacrament and a focus on transubstantiation.

Participants in the Salt Lake City Diocese's Eucharistic Rally and Mass July 9 at the Mountain America Expo Center in Sandy, Utah, spend time in adoration before the Blessed Sacrament. The diocesanwide event was the culmination of the "Year of Diocesan Revival," the first stage of the National Eucharistic Revival. (OSV News/Sam Lucero)

My plea here is for something more. Or more correctly for something missing: to reclaim the Gospel vision and early Christianity's practice of nonviolent love — the Eucharist's inherent summons to active peacemaking.

Jesus taught the love of enemies and then lived it by confronting violence without retaliation, by refusing to respond to brutality with revenge, by forgiving his executioners and, in the end, by breathing the Spirit of peace into the very disciples who had denied and abandoned him.

How did we lose this bond between the breaking of the bread and active, nonviolent love?

The reasons for this are complex, but two stand out: the transformation of the "Jesus movement" into Christendom, and the resulting cultural-religious amnesia as to why Jesus was executed by crucifixion.

From Gospel nonviolence to 'just war'

Most of us were taught that emperor Constantine's vision ("In this sign, you will conquer") was the turning point for an oppressed minority of believers, decimated by persecution and martyrdom. The familiar narrative is that Constantine converted to Christianity. But it is more accurate to say that Christianity converted to the empire. Christianity became Christendom.

A statue of the emperor Constantine stands outside the Basilica of San Lorenzo Maggiore in Milan, Italy. (Wikimedia Commons/Giovanni Dall'Orto)

Adopting the architecture, religious vestiture and organizational style of the Roman empire, the church also endorsed St. Augustine's theory of the just war. Instead of looking to the teaching of Jesus, the church has relied on this political/philosophical reasoning to justify collaborating with the state in going to war. Often, as is happening in Ukraine today, this involves Christians killing other Christians in the name of God.

But "just war" is not constrained by religious boundaries. Constantine turned the cross upside down, converting it into a sword, an icon of violent conquest. We Catholics still bear the cruel memory of the crusaders (from crux, crucis), who, with the blessing of popes, murdered Muslim "infidels" with the cross proudly displayed on their shields and battle flags.

As Joseph Campbell ruefully puts it in The Power of Myth, "Peter drew his sword and cut off the servant's ear, and Jesus said, 'Put back thy sword, Peter.' But Peter has had his sword out and at work ever since."

Reclaiming the dangerous memory

As Christianity evolved into Christendom, Jesus' mandate to love and forgive the enemy gradually evolved into an over-spiritualized ethical ideal, which foreclosed on the call to create peace through justice instead of through military victory.

This, in turn, resulted in the spirituality of the Eucharist shifting from nonviolent love to a focus on the Real Presence. Instead of summoning us to follow the nonretaliatory way of the cross, the sacrament became a presence to be adored, often with little connection to the oppressed, suffering body of Christ in the world.

Jesus didn't die for our sins. He died for our systems: for the structural oppression, the systemic violence that we need to maintain our lifestyle and our national 'security.'

This is at best a truncated spirituality, and at worst a distortion of the teaching and ministry of Jesus. It creates a private piety centering on Christ's real presence in holy Communion, the tabernacle and monstrance, but unmoored from his call to confront structural violence with nonretaliatory love.

When we read the Gospels through the eyes of contemporary biblical theology, it is difficult to disregard Jesus' mandate to confront systemic evil through both personal and communal nonviolence.

We cannot reclaim this mandate unless we also retrieve the religious and political matrix in which Jesus lived and died. As theologian John Dominic Crossan reminds us, we cannot understand the text without the context.

Jesus was a dark-skinned Aramaic-speaking Galilean peasant. If he were among the Central American refugees seeking asylum in the United States today, he would likely be pushed back into the Rio Grande by right-wing Christians. Like migrants in our time, Jesus and his family had to flee for their lives to a foreign land (Matthew 2:13-18). When he returned, Palestine was still an occupied country, under the heel of the Roman legions and their religious collaborators.

Bishop José Guadalupe Torres Campos of Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, distributes Communion during a binational Mass in memory of migrants who died during their journey to the U.S., near the border between Mexico and the United States in Ciudad Juárez Nov. 6, 2021. (CNS/Reuters/Jose Luis Gonzalez)

True to his Jewish roots, Jesus reclaimed the heart of the Torah as God's distributive justice and unconditional love. His radical teaching on nonretaliatory resistance by loving one's enemies and forgiving them was a direct confrontation with the imperial occupation — a counter-kingdom to Caesar's brutal Pax Romana. Jesus was not put to death because he was kind or compassionate; he was executed by Rome because his preaching and way of life were a threat to the empire.

German theologian Johannes Metz describes this as the "dangerous memory" of Jesus of Nazareth. For most Western Christians, this is an inconvenient truth.

As a result, over the centuries, we created a more domesticated version, including a warped theology of atonement that portrays Jesus as a Euro-white savior who in effect "takes the hit" for us, thereby relieving us of guilt by substituting himself for our personal sins.

Advertisement

But Jesus didn't die for our sins. He died for our systems: for the structural oppression, the systemic violence that we need to maintain our lifestyle and our national "security." But this only adds a dangerous political illusion to a theological distortion. The cross is not about security or substitution; it is about participation in the nonviolent Christ.

The Eucharistic is not only a presence. It is an insistence, a summons to follow the Suffering Servant in his final act of resistance on the cross — resistance to what New Testament scholar Marcus Borg calls the "domination systems" that are entrenched as the normality of civilization.

"The Eucharist is the sacrament of nonviolence." This is the unequivocal assertion of Cardinal Raniero Cantalamessa. Since he has been the official preacher to the papal household for 43 years (appointed by St. John Paul II in 1980), we can safely assume that his reflections come with some theological heft. He has, after all, preached to three different popes, and who knows how many cardinals, archbishops, bishops, priests and other members of the Vatican Curia. Pope Francis made him a cardinal in 2020.

In the synodal spirit of Francis, I offer this suggestion to the U.S. bishops: Invite Cantalamessa to give the keynote address for the closing of the eucharistic revival next summer.