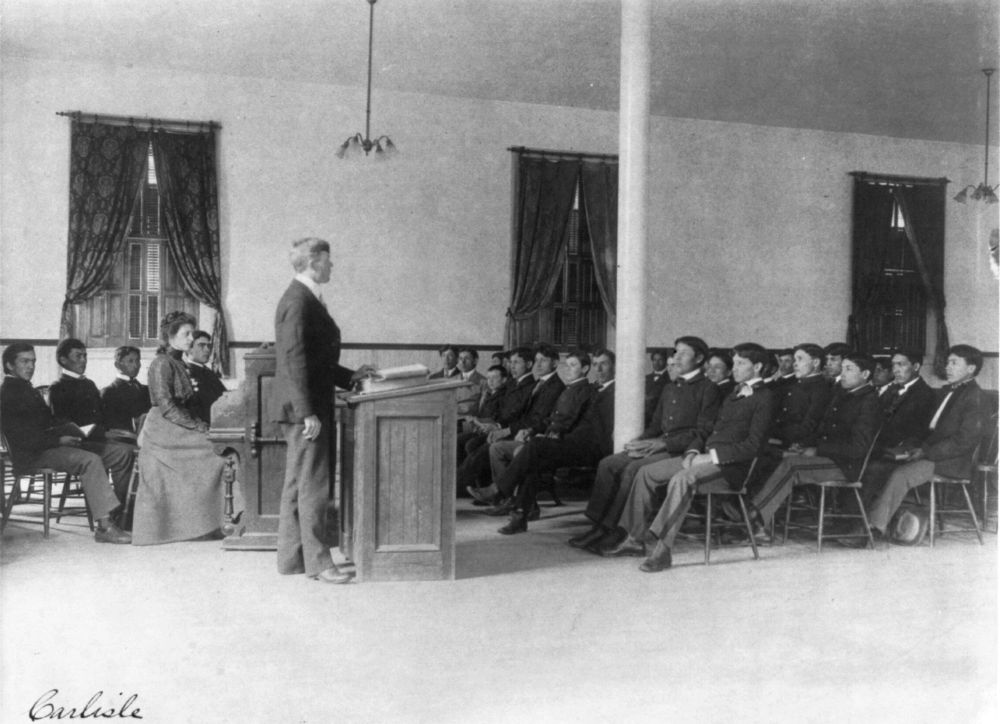

Native American boys attend a chapel service at the Carlisle Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, 1901. (Francis Benjamin Collection, Library of Congress)

Last week, Dr. Renita J. Weems, a theologian, author and ordained minister in the African American Episcopal Church, posed a question on Twitter:

What does the Admin plan to do with these children warehoused around the country? Over 200 girls flown to and warehoused in NY, (one as young as 8 months!)? Any ideas?

My idea was this:

My guess is that white Evangelical families eager to show their compassion, build God's Army, and assimilate brown children will advise their friend Pence to let them step in with "adoptions" of some sort and pat themselves on the back for their kindness.

For a second, the response I was about to post seemed mean. I worried for a moment that my cynical tone and use of stereotypes might offend someone, but then I visualized a photo I came across last year while working on a story about "States of Incarceration," a national exhibition that reckons with the country's history of incarceration in different states and regions. The photo I remembered was taken in 1863. It shows Episcopal Bishop Henry Whipple, centered, wearing a white robe and cleric's stole, holding an open book and surrounded by tents and Native Americans at the Ft. Snelling concentration camp in Minnesota.

An historical briefing for context: Following their losses in the Dakota War, some 1,700 surviving tribe members were forced to march from their land to Ft. Snelling. Soon after, boarding schools — the first of which the Bureau of Indian Affairs established in 1860 on the Yakima Reservation (now the state of Washington) — would open across the country. Under legislation from the U.S. government that encouraged and supported assimilation of Native Americans into mainstream, Anglo-American culture, Native American children would be taken from their families and placed in those schools.

In an episode of "We Shall Remain: Wounded Knee," from the PBS documentary series "American Experience," Walter Little Moon, an Oglala Dakota survivor of the forced removal, described the experience as "torture, brainwashing. They called us many different names. Savage. Dumb. We got beat for looking like an Indian, smelling like an Indian, even speaking Indian." Video from the episode shows animation of brown children walking into concrete buildings and lining up to sit in a barber's chair and have their hair cut off. Dennis Banks, an Anishinaabe and also a survivor, said of the experience, "It destroyed our family. I could never regain that friendship, love relationship I had with my mother."

Advertisement

As the photo of Bishop Whipple indicates, the assimilation process involved converting Native American children to Christianity. Many boarding schools in Minnesota, for example, were administered by the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions. The schools, in the eyes of the missionaries, were as essential to the Great Commission as Manifest Destiny was.

There are differences between Native American children and the children from Mexico and Central America whom government officials have removed from their families (or who arrived as unaccompanied minors and are now in prison-like facilities). In the present-day case, the government didn't take the children from their home, just from their families at the border. Additionally, given that Latin America is predominately Catholic, conversion won't be needed. Both groups, however, have been depicted as savages, cast as criminals, accused of desiring the destruction and takeover of white American language, culture, values and numbers.

There also is a difference between the atmosphere of today and that of the 1860s. Today, numerous studies have shown the majority of white Evangelicals believe they, as Christians, are the ones under attack. They don't feel the dominance and control they felt in the 19th century. They feel instead that the soul of their country is at stake. In this present era, the more they can erase any connection to and love of the people, countries and cultures they have systematically othered, the stronger their numbers and the greater their chance of re-ascent into dominance. And just as they have convinced themselves of the president's adjacency to God — just as their ancestors convinced themselves of Manifest Destiny, the Hamitic myth and biblical order of slavery — they will convince themselves their actions are good for the children.

The insidiousness I've outlined here isn't far-fetched. This legalized practice of separation and forced assimilation affected more than 100,000 Native American children in 500 boarding schools and lasted until the 1960s. Its end is not so long ago that the process can't begin again.

So I'm not worried about being unkind, uncivil or offensive. I'm worried about there being another Dennis Banks.

[Mariam Williams is a Kentucky writer living in Philadelphia. She holds a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing and certificate in public history from Rutgers University-Camden. She is a contributor to the anthology Faithfully Feminist and blogs at MariamWilliams.com. Follow her on Twitter: @missmariamw.]

Editor's note: Don't miss Mariam Williams' column, At the Intersection. We can send you an email every time a new one is posted. Click on this page and sign up.