(Unsplash/Nhia Moua)

On a recent afternoon in the refrigeration room at the Georgetown University School of Medicine, the temperature was a stabilizing 36 degrees. About a dozen cooled bodies, wrapped in plastic plus additional coverings for heads, hands and feet, were neatly stacked on metal frames. Each cadaver had been embalmed and in time — a few days, a week, a month — would be wheeled to a nearby laboratory to be placed on tables and dissected by medical students.

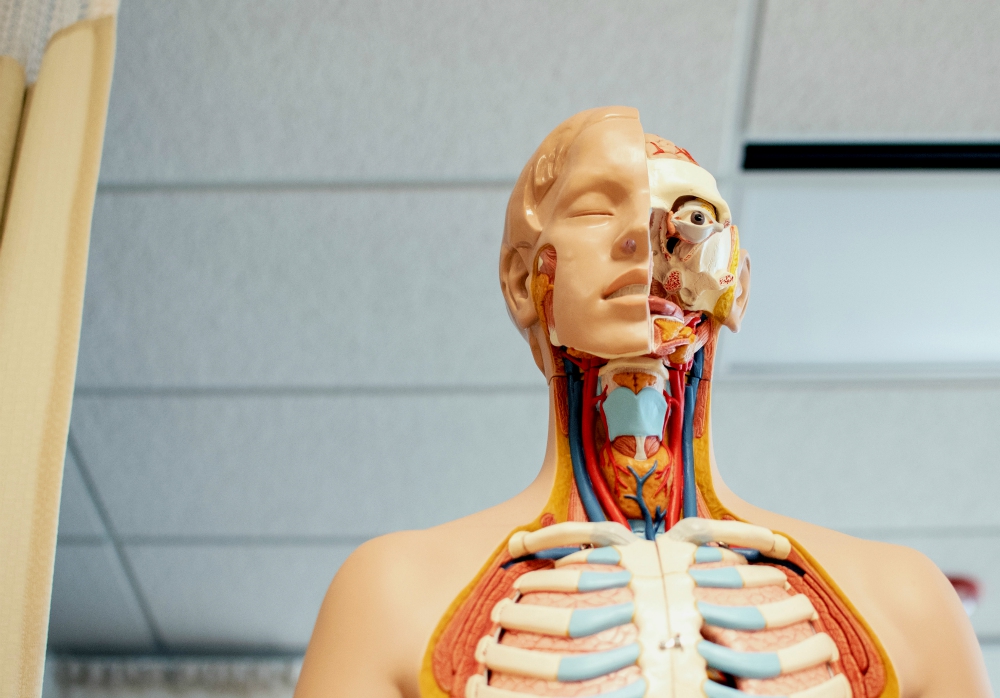

At one semester or another, future physicians come to an anatomy lab twice a week for four months of four-hour sessions to learn all they can about the 206 bones and more than 600 muscles in the average adult body, along with the different axial skeletal and appendicular skeletal systems. Cadavers in the lab were donated by someone who properly filled out an anatomical donor form.

I'm one of them.

Not that I am in any kind of hurry to be sliced open, however much I admire medical students for taking on the anxieties and arduousness of their education and then the pressures of residencies. But now that I'm 81, mortality thoughts do creep in as they never did when I was 30, hale, carefree and with no Grim Reaper fears.

Whenever my inevitable cardiovascular shutdown may be, I've made several visits, curiosity-driven, to Georgetown's anatomy labs during the dissections. The first time, crasher though I was, none of the students minded if I looked on as they gently cut into and examined body parts. For a few moments at one table, the discussion was less about the strengths and weakness of the ligaments in front of them than a lively chatter on whether the group preferred going to a Mexican or Chinese restaurant after class ended at 5 p.m.

Looking around the lab and its 10 tables, I found myself wondering what kind of medicine would these aspirants one day practice. Who would become pediatric neurosurgeons? Jungian psychiatrists? Obstetricians who performed home births?

Who might be sued for medical malpractice? Who would join Doctors Without Borders?

On my second drop-by, I was greeted by Carlos Suárez-Quian, who was immediately friendly and welcoming. I recognized his name, acclaimed author that he is and a longtime professor in Georgetown's Department of Biochemistry. While he and the students took a break from dissecting, I explained that I was a donating a body that might be a bit singular: I'm a vegan, have never smoked, bibbed booze or sipped caffeine, have run 18 marathons and dozens of 10-milers, and have commuted by bicycle more than 60,000 miles since 1969 when I joined the editorial board of The Washington Post.

I asked Suárez-Quian if he sees many bodies like mine. He chuckled.

Gratefully no, he said: You're way too healthy; the dissecting students would learn little. And more jocularity: Start eating meat, drink whiskey and take up smoking. Then you'll be a prize donor. The students will learn plenty.

On another visit, I had some time with Mark Zavoyna, 53, the cadaver lab director for the past 10 years. He attended mortuary school from 1989 to 1991, followed by four years in the Army, including serving as a combat medic in Desert Storm. A licensed mortician, he leaves his home near Baltimore at 4 a.m. Well before the daily hospital bustle begins, he is most likely embalming a body, an effort that usually takes four hours. He graduated from the Catholic Calvert Hall College High School in Towson, Maryland.

"There is a peace that comes in caring for the deceased," he told me. "I wear the medal of St. Joseph of Arimathea, the patron saint of funeral directors."

On the question of how the medical students emotionally deal with dissecting, he said, "It can be a little difficult. This is the first time doing anything with someone who has died. Stress is there. They're in medical school and there's a lot of stress to begin with.

"But as you would expect, the dissecting becomes a little more mechanical. I suppose my favorite personal satisfaction in working with medical students is simply my daily interaction with them. While I get some satisfaction from the fact that I contribute in some small way to their education, it's the knowledge I gain from them that is most satisfying to me."

Advertisement

Zavoyna, whose father immigrated from Czechoslovakia and whose mother has Irish roots, estimates that 55% of the donors are women and 45% men.

"Dr. Suarez and I believe," he says, "that because the men are often the first to die, the widow or surviving spouse is generally more inclined to honor their loved one with a more traditional funeral. Often, prior to their own death, this spouse is more likely open to donating their remains. They often feel that it affords them the opportunity to give back. Their children are usually more open to alternative forms of disposition. Many of our donors are almost 'giddy' about the opportunity to give back to society, even in death. They have lived a good life and feel that they owe this to the world — in a sense, payment for a life well-lived."

In recent weeks, I've come to know Amanda Kuhn, a second-year medical student who went to Whitman High School in Bethesda, Maryland, and on to Carnegie Mellon University.

"I can remember our first lab vividly," she wrote to me. "None of us really wanted to make the first incision, not necessarily because we were afraid of what we would find, but because of the human element. Every donor was likely at one point a sister or brother, a mother or father, a friend, or at the very least, a soul. There was an unspoken but overwhelming sense of appreciation that I, and I believe many of my peers, felt to have an opportunity to learn from someone who did not know us personally but chose to donate their body for our education."

The learning came also from those dissecting on the other side of the table.

"The anatomy groups consist of four or five people, and they remain the same for the whole year," Kuhn said. "By nature of the many hours we spent in the lab, my group became very tight-knit. We were challenged to work and make decisions as a team, and further, we all shared in this powerful, transformative, extraordinary experience together. Some of my fondest memories of medical school to date are from my anatomy lab."

In late October, the medical school class of 2022, of which Kuhn is a member, gathered at Georgetown's Gaston Hall along with about 70 relatives of the donors for a religious ceremony based on gratitude and remembrance. Two Jesuit priests celebrated a Catholic Mass after representatives of Jewish, Hindu and Islamic faiths spoke.

Seeing the medical students in their white jackets and carrying candles in the Procession of Lights had me recalling some capacious lines from Kuhn's letter that all her classmates could be feeling.

"My decision to pursue a career as a physician didn't stem from a particular person or event but largely from a deeply-rooted desire to help people," she wrote. "Health is often something that many of us take for granted, until it's impaired in some way. Through participating in volunteer experiences growing up that were both in and outside of a medical setting, I realized that I experience a strong sense of purpose when I can improve a person's situation or empower them to reach their greatest potential, and a large part of that starts with listening to people and meeting them where they are."

On Oct. 17 at 7:45 a.m., Kuhn and one of her anatomy lab tablemates spoke to my Peace Studies class at Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School, offering stories on why they chose medicine and how they handle the anatomy labs. It's not a wild guess that if a few students in the class go on to become doctors, they will look back to remember Kuhn inspiring them that morning.

[Colman McCarthy teaches courses on nonviolence at three universities: Maryland, American and Georgetown as well as Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School. His new book is Opening Minds, Stirring Hearts.]

Editor's note: Sign up here to get an email alert every time Colman McCarthy's It's Happening column is posted.