Joan Baez singing to a sold-out audience in Albany, New York, at the Egg Performing Arts Center in 2016. (Wikimedia Commons/Jim Gilbert)

More than a decade ago, I wrote to the chair of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, expressing my hope that that year, 2010, would be the one in which Joan Baez would be one of the honorees for the center's annual award for the performing arts.

"She has used her gifts fully," I wrote, noting that she had given more than 40 concerts a year since the late 1950s, when she began singing in the folk clubs of Boston. "Her voice remains as pure as it was when the nation first heard it at the 1959 Newport Folk Festival. Equally so, her commitment to nonviolence and human rights has been unwavering."

Advertisement

In my letter, I shared with David M. Rubenstein that I came to know Baez in the early 1970s when I was a columnist and editorial writer for The Washington Post. We would meet when she was passing through Washington on her way home to California from concert tours in Latin America, Europe and Asia. During those meetings, she would give me information about political prisoners she met in places like Chile, Northern Ireland, Poland, Turkey or the Middle East. With the documentation — always sound — I wrote columns about the prisoners and their mistreatment.

"Her organization, Humanitas International, was as much a voice for human rights and disarmament as Joan's own voice onstage," I wrote to Rubenstein, noting that she helped establish a West Coast office for Amnesty International and marched with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in Mississippi, Cesar Chavez in California, Mairead Corrigan in Belfast and Lech Walesa in Poland. In 1972, she visited POW camps in North Vietnam and took to underground shelters to survive President Richard Nixon's Christmas B-52 bombing raids in Hanoi.

"I've done lots of things in my lifetime, and I know that I am least happy when I am least involved in social action," Baez wrote in an essay, "The Courage of Conviction."

Native American Floyd Red Crow Westerman, protest singer Joan Baez, actor Martin Sheen and the Rev. Cecil Williams, pastor of the Glide Church, join in protest during an anti-war march in San Francisco Jan. 18, 2003. (CNS/Reuters)

"Joan is the antithesis of the celebrity dabbling in the cause of the day," I wrote in my letter to the Kennedy Center. "Her principled stances on political issues are matched by a fidelity to her music."

In October 1986, during a visit to Washington for a concert, Baez stayed at my home for a few days. Every afternoon for three or four hours in our guest room, she would practice her voice lessons. When you are given a gift, she explained, you need to cherish it, not let it rust.

While in Washington then, she took time to speak to my peace studies classes at American University. I had arranged for her to give a free outdoor concert on the quad in the early afternoon, and then come to speak and exchange ideas for two and half hours with my students. The year before, she hosted a post-concert seminar at Constitution Hall for 40 of my students from The School Without Walls, which, by the way, is the closest school to the Kennedy Center. At least two dozen times over the years, Baez has supplied free tickets and backstage passes to my high school and college students.

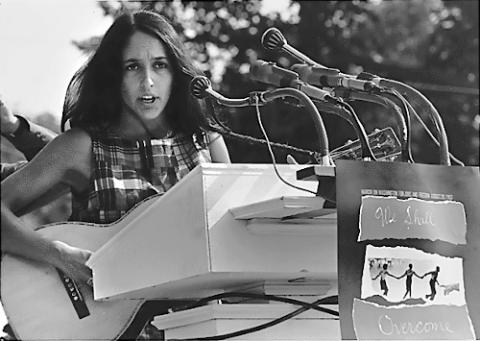

Vocalist Joan Baez performs at a civil rights march on Aug. 28, 1963, in Washington, D.C. (Wikimedia Commons/U.S. Information Agency/Press and Publications Service/Rowland Scherman)

"I'm hard put to think of any musician whose professional life onstage is as uplifting as her commitments to justice and peace are strong in her personal life offstage," I wrote, ending by recommending that she is "perfect for a Kennedy Center award."

I didn't receive a reply from Chairman Rubenstein, a billionaire well-known philanthropist and a busy man with little free time. I understood. What was hard to fathom, though, was why he and the center's trustees had never honored Baez.

From the date of my 2010 letter and 2020, nearly 70 performers were awardees, including Reba McEntire, Carmen de Lavallade, Shirley MacLaine, Lily Tomlin, Gloria Estefan, Linda Ronstadt and Carole King. I don't mean to be picky, but are any of these even remotely close to the heights reached by Joan Baez? Pardon, I think not.

Amends, of a sort, have been made. On Jan. 13, just days after Joan turned 80, it was announced that she would be honored, along with Debbie Allen, Dick Van Dyke, Garth Brooks and Midori. Postponed because of the pandemic, the pre-recorded ceremony will be broadcast at 8 p.m. Eastern on June 6 on CBS and on Paramount+.

Ever gracious, Joan wrote appreciatively about being chosen: "It has been my life's joy to make art. It's also been my life's joy to make, as the late Congressman John Lewis called it, 'good trouble.' What luck to have been born with the ability to do both; each one giving strength and credibility to the other. I am indebted to many for a privileged life here. I've tried to share my good fortune with others anywhere and everywhere in the world. Sometimes there have been risks, but they are only a part of the meaning of it all. I extend my deepest thanks to the Kennedy Center for recognizing me, my art, and the good trouble I've made."

As a repeated recipient of Joan's good fortune and generosity, I expect to continue to have her ideas and ideals a major part of my peace studies courses, starting with her memoir "And A Voice To Sing With" as a text. For a research paper, I ask students to interview their parents and grandparents on how Baez stirred their hearts and inspired them to work for peace. I also encourage them to buy one of her 30-plus albums and to treasure it.