John McCarthy, left, with Sen. Eugene McCarthy, in an undated photo (Provided)

Cringing is an emotion that I manage to control. Most of the time. Lately, though, I've become a cringer. The angst moments swell up whenever I see Rep. Kevin McCarthy standing ramrod tall and stern-faced next to Donald Trump as the president spouts lie after lie, brag after brag, insult after insult. McCarthy, a Republican representing California's 23rd district since 2007, is the House minority leader and, acting like a political henchman, he knows his role in life is to suck at the roots of power — Trump's power, in all its shambolic sickening forms.

If McCarthy's name wasn't McCarthy, I wouldn't be cringing. But it's tribal pride. Clan honor. A McCarthy shouldn't be bonding with a scabrous venal scammer like Trump. McCarthys are from a royal Gaelic gene pool that ought not to be sullied by apostasy, which is what shilling for Trump amounts to. We go back to the 12th century when King Cormac of Munster reigned. The original spelling, Mac Cárthaigh, was Anglicized to McCarthy while the meaning of the name remained: "son of the loving." (Mac means "son," Cárthaigh "loving.") Hard to top that.

Advertisement

Witnessing Kevin McCarthy despoiling himself — he follows Trump around like a leashed puppy — is a reminder of the early 1950s when another befouling tribesman was in Congress: Sen. Joseph McCarthy. The Wisconsin Republican, who earned a law degree from the Jesuit Marquette University and served in the senate from 1947 until his death at age 48 in May 1957, rose to fame by giving a speech in February 1950 to the Ohio County Women's Republican Club in Wheeling, West Virginia. He railed that the State Department was packed with "members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping policy." With little evidence, he named names.

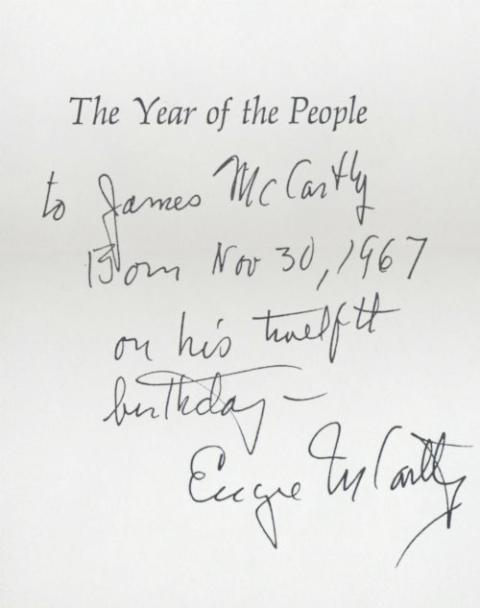

Image of the inscription in Eugene McCarthy's book, which was a gift (Provided)

Conservatives blindly cheered the demonizing McCarthy and his abusiveness, but for others he was no more than a smearer and a reckless bully. Weeks after the fractious Wheeling speech, Herbert Block of The Washington Post coined the word McCarthyism in a cartoon that ran on the editorial page. The term stuck, to be immortalized in Webster's dictionary as "using tactics involving personal attacks on individuals by means of widely publicized indiscriminate allegations esp. on the basis of unsubstantiated charges."

The senator himself saw the word as a positive, even celebrating it by writing a book titled McCarthyism: The Fight for America. His dopaminergic high didn't last long. McCarthy would be censured by the Senate in 1954 and die three years later an alcoholic and broken man.

For a time while McCarthy was crusading against the "Red Scare," his chief counsel and corner man was a legal prodigy, Roy Cohn, a graduate of Columbia Law School at age 20. Leaving government toil, he would go on to be a New York lawyer with a client list that included Mafia thugs, the Archdiocese of New York and a rising Manhattan real estate hustler, Donald Trump. For a dozen years, Cohn avidly mentored the future president in the gutter tactics he learned from McCarthy. Slime opponents, spew lies about them and practice verbal violence against them — each feral method on full display these past two years and decades before. In essence, Trump is a McCarthyite, another grandiloquent word enshrined in Webster's unabridged eternal volume.

Amid the darkness brought on by Kevin and Joseph McCarthy and their cringe-causing degradations of their name, other McCarthys were dead-correct honest, humane and soulful when they graced the halls of Congress.

Start with Eugene McCarthy. The one-time Benedictine novice, semi-pro baseball player in the Soo League, poet, essayist, father of four, a high school and college social sciences teacher and presidential candidate came from Minnesota to serve a decade in the House from 1949 to 1959 and the Senate from 1959 to 1971. I came to know and love Gene, mostly through visits to his home across the street from the National Cathedral, one he shared with his wife Abigail, a writer whose wise words illumined the pages of Commonweal and her book Private Faces/Public Places.

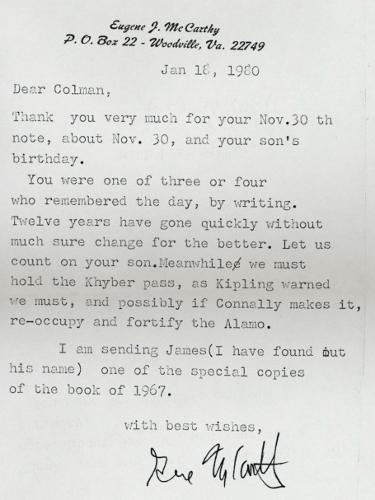

Letter from Eugene McCarthy (Provided)

By chance, Nov. 30, 1967, was a memorable day for the McCarthy clan: Gene announced his anti-war candidacy for the presidency, and my wife Mavourneen delivered our first-born son, James. I wrote to Gene to tell him how overjoyed I was by the coincidence, plus offering my support for his run, much of which was based on quickly ending President Lyndon Johnson's horrific Vietnam War. Gene wrote back a gracious note, along with a signed copy to James of one of his poetry books. It wasn't a one-time gift. The Year of the People, Gene's stirring and literate account of his 1968 campaign, came in the mail in a leather-bound copy inscribed "To James McCarthy, born November 30, 1967, on his 12th birthday, Eugene McCarthy."

There were other generosities. Days after a get-together with James and his two younger brothers, in which the conversation was totally about baseball, Gene sent an autographed picture of himself swinging right-handed and likely pulling a line drive to left field. The next time all of us met, one of my lads, John, perplexed, asked Gene why he gave up playing baseball: "You could have become a famous big leaguer and now all you are is a senator." Gene hugged the lad.

Then we have Carolyn McCarthy, a Republican who became a liberal Democrat from Long Island and a nurse whose direction in life was radically altered on Dec. 7, 1993, when her husband Dennis was one of six railroad passengers murdered and her son among the 19 wounded at a stop in Garden City, New York. Three years later, after becoming a major and nationally known advocate for sane gun laws, she was elected to Congress — and from a mostly Republican district, at that.

Although her persistent stands on gun control led to her being labeled by many as a one-issue politician, her causes were wide and deep. They included backing the Northern Ireland Peace and Reconciliation Act of 2003 to sponsoring legislation for child health care and humane treatment of veterans.

And one more McCarthy, if I may: my father John Patrick. The son of a school janitor, he was elected in the 1940s to be the city attorney of Glen Cove, Long Island. Much of his practice was immigration law when instead of today's Tijuana and Brownsville, Texas, as major points of entry it was Ellis Island in the New York harbor. Whether his clients were Jewish families fleeing Germany in the 1930s and 40s or the impoverished from Eastern Europe, he did it pro bono. He earned enough from a few wealthy clients on the Gold Coast of Long Island — the J.P. Morgans, the Harrimans — to spend time finding jobs for the immigrants as gardeners, cooks, chauffeurs, maids and caddies.

I'd better stop now, though I could go on and on about still more McCarthys, ones who are descended from Gaelic kings and lived up to their name: writers like Mary McCarthy and Cormac McCarthy and the New York Yankees manager Joe McCarthy, who won seven World Series tiles. The Yankee Clipper Joe DiMaggio hailed him: "Never a day went by when you didn't learn something from Joe McCarthy."

Couldn't the same be said of Gene, Carolyn and John Patrick?

[Colman McCarthy's forthcoming book is Opening Minds, Stirring Hearts.]

Editor's note: Sign up here to get an email alert every time Colman McCarthy's It's Happening column is posted.