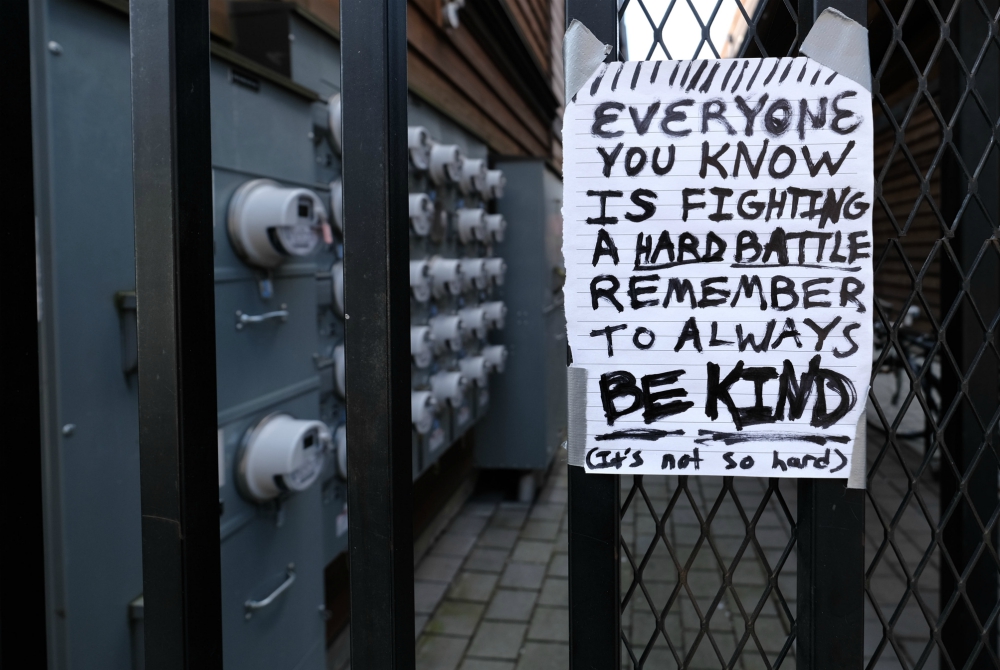

Pedestrians walking along Mississippi Avenue March 18 in Portland, Oregon, could see this handwritten message that acknowledged people are frightened amid the coronavirus pandemic but encouraged them to be kind to one another. (CNS/Reuters/Alex Milan Tracy)

In a matter of a few weeks, the world has shrunk.

We've become our neighborhoods in a microscopic sense. We've become the last surface touched, the last person we've passed, the last hint of an ache or shiver that could mean you-know-what.

In our condo building in Maryland, just outside the Beltway, hundreds, if not thousands, of people live side by side and atop one another for 20 floors. Life in normal times is a practiced art of engaging as well as providing social distance. That art, given elevators and common spaces, now has been reduced to polite avoidance all the time.

While there seems so much to be done, in reality the mandate for most is to do nothing, as little as possible, to remain in place. "Stay still!" The command has always had the opposite effect.

Nearly 20 years ago, I experienced a forced retreat after some serious surgery. I reflected at the time that while "such an event simultaneously shrinks one's entire universe to, say, the 6-inch space between the edge of the bed and the chair that is that morning's goal," it also "expands that universe to thoughts well beyond the mundane," beyond what one normally perceives as the most pressing issues of the day. Crises force us to change our ways of thinking.

The paradoxes pile up today: how to allow the world to shrink but not be subdued by fear; how to engage in the thoughts unbounded save for our imagination yet remain in the present. We're forced in unusual ways to understand our common humanity, an understanding made possible technologically as never before. Yet we are forced to stay away from one another.

Still, we find ways to connect.

A place where I've experienced in a practical and profound way that sense of common humanity is the parish of St. Camillus in nearby Silver Spring, where my wife and I are members. The world has dropped into this place, the largest parish in the Washington Archdiocese, run by Franciscans, members of the Order of Friars Minor. About 80 countries are represented in the congregation, which is 57% Hispanic, 25% Euro/Anglo, 10% African and 4% Asian, according to the pastor, Fr. Chris Posch, who refers to himself as "Brother" and lists himself in the bulletin not as pastor, but as Servant.

When the virus slammed the brakes on the world, the jolt was telling for St. Camillus, a community of 2,300 registered households, likely a serious undercount because, as Posch put it, "we suspect that many of our parishioners don't register because that's not the custom in their home countries."

Pews are seen at St. Camillus Church in Silver Spring, Maryland, in 2018. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

All but one of the parish's 160 ministries closed down. In the parish mission in nearby Langley Park, whose population Posch describes as "the poorest of the poor and most vulnerable who are the richest in faith and generosity," he had to close down the Catholic Center, as well as Sunday and weekday Masses, prayer groups, youth groups and English classes.

But on March 15, the parish livestreamed three Masses, one in English, another in Spanish and another in French "and we had over 5,000 viewers, which is the same amount of people that we get at weekend Masses," said Posch. "A lot of people liked the livestreamed Masses so much that they want daily messages. They want to feel connected to the parish and see a familiar face and hear a familiar voice. So we're experimenting with it now."

That set him and three other Franciscans who make up a community of priests responsible for various ministries at the parish thinking about other ways to connect with people who are anxious or uncertain about the future and want to retain a connection with some expressions of faith.

Posch's perspective on the current situation begins a week earlier, during the liturgies and some parish events on Transfiguration Sunday. "Many of us had great experiences at Mass or preaching or good conversations. We had an intercultural potluck. Just a tremendous day. For many of us it was like a mountaintop experience, and often when we have these kind of mountaintop experiences, God is preparing us for some struggle that lies ahead."

So much remains unknown. One of the events postponed was a retreat for 60 teenagers in the parish scheduled for this month. And the friars are still puzzling out what to do with Easter celebrations. More than 100 are scheduled for sacraments of initiation at the Easter Vigil, a multicultural, multilingual observance that annually is an exuberant expression of faith gathered in from all corners of the globe.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, young people are volunteering to replace older volunteers at the food pantry and delivering meals on wheels. A restaurant owner, said Posch, has volunteered to deliver food to shut-ins. Others are writing notes to people in hospitals who can no longer have visitors. "We're seeing this as a struggle," said Posch, "but we're also seeing it as an opportunity."

I am certain it is but one story in a growing anthology of hope and creative connections occurring by way of the Catholic community across the country.

I confess that I can be quite grumpy about social media, especially when my resistance wears down and I get caught in its tug. "Did I really spend that much time skipping from Facebook to Twitter to Instagram to email to … Oh my God, all the text messages that have piled up. And it's our day to Facetime with grandkids."

It usually ends with a short-lived vow to lock up the phone and weak rationalization that my work makes all of that connecting essential.

These days, of course, social media has become indispensable and is showing its best side. In an email response to some alumni, Fr. James Greenfield, an Oblate of St. Francis de Sales and president of DeSales University in Center Valley, Pennsylvania, left the group with the prayer below. He had received it from a friend and had used it at the end of a class he taught (remotely) called "Introduction to the Devout Life."

He eventually traced it back to the Instagram account of krugthethinker, aka Cameron Bellm, who describes herself as "Writer of prayers. Seattle mom & maker. Generally just bumbling around, thinking about God." Her account displays a lot of lovely and interesting other thinking about God.

She has invited people to share the prayer.

Prayer for a Pandemic

May we who are merely inconvenienced remember those whose lives are at stake.

May we who have no risk factors remember those most vulnerable.

May we who have the luxury of working from home remember those who must choose between preserving their health or making their rent.

May we who have the flexibility to care for our children when their schools close remember those who have no options.

May we who have to cancel our trips remember those who have no safe place to go.

May we who are losing our margin money in the tumult of the economic market remember those who have no margin at all.

May we who settle in for a quarantine at home remember those who have no home.

As fear grips our country, let us choose love.

During this time when we cannot physically wrap our arms around each other, let us yet find ways to be loving embrace of God to our neighbors.

Amen.

[Tom Roberts is NCR executive editor. His email address is troberts@ncronline.org.]