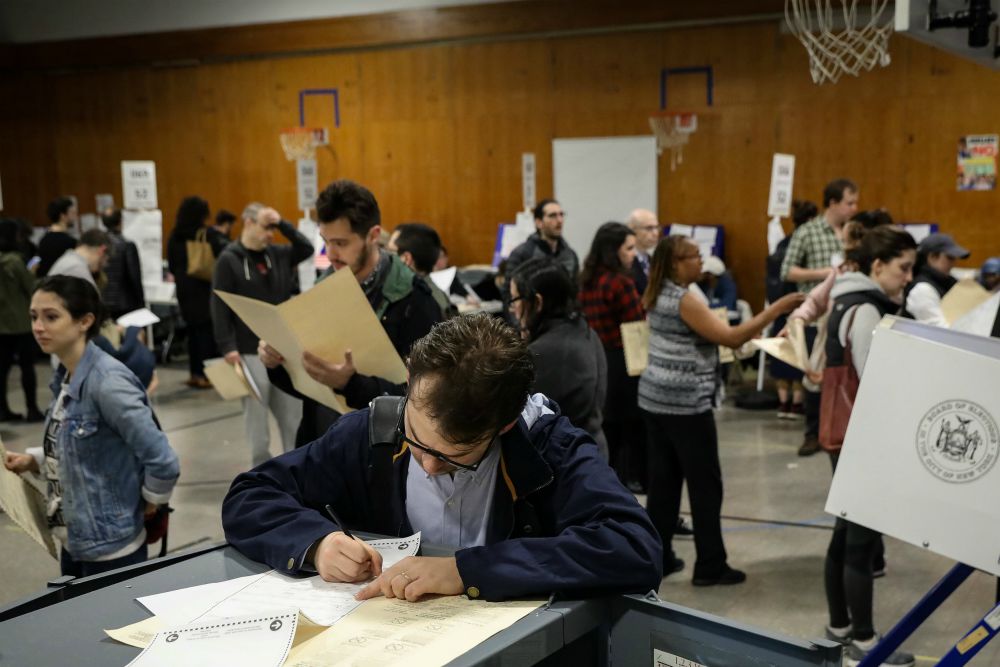

A voter fills out his ballot in the midterm elections Nov. 6, 2018, at a polling station in the Brooklyn borough of New York City. (CNS/Reuters/Brendan McDermid)

It apparently isn't enough that Russian hackers interfered in the 2016 elections and have even more sophisticated means aimed at 2020. Or that Republicans have taken brazen steps to suppress the vote, especially among people of color. Or that Democrats and Republicans have gerrymandered congressional districts so that they don't have to contend with people who disagree with them in order to keep their seats.

Now we have conservative Catholics engaged in "geofencing," digital era jargon for surreptitiously gathering information from the phones of unsuspecting citizens, in this case specifically, Catholic citizens headed to church.

The surreptitious aspect has been nullified somewhat by the fact that the organization undertaking the underhanded practice, CatholicVote.org, has been bragging about its data collection efforts. Any further cover has been blown by the reporting of NCR National Correspondent Heidi Schlumpf, who detailed how it happens and who is engaged in it.

"Here's how it works: Politically minded goefencers capture data from the cellphones of churchgoers, and then purchase ads targeting those devices," she writes.

"The data can be matched against other easily obtained databases, including voter profiles, which give marketers identifying information such as names, addresses and voter registration status."

There's probably little that can be done legally to stop it. If the Supreme Court can confer personhood on corporations in the name of political free speech, what can churches expect in any attempt to protect their members from becoming targets of information collected in the cause of political campaigning?

But some suggestions for individual action:

- Go to the link on our website and share it widely with friends and fellow parishioners;

- Send the story to your pastors and your bishop. Ask them to make sure people know going to church might make them targets of data hunters;

- Make copies and pass them out at church or post on a common bulletin board;

- Let us know of any other ideas you have for spreading the word.

And as you head to church? Leave the phone at home, or turn it off well before you reach the parking lot.

Advertisement

______

The year at Boston College began with an ambitious Jan. 2-3 conference that bore the heading "To Serve the People of God: Renewing the Conversation on Priesthood and Ministry." A heady topic, and a roster of heavy hitters took their places behind closed doors to discuss.

Among those attending were five bishops, an archbishop and three cardinals: Joseph Tobin of Newark, Blase Cupich of Chicago, and Reinhard Marx of Munich and Freising, Germany. Also attending were rectors of five important seminaries; the president of Catholic Theological Union, Chicago; and theologians from a host of other colleges and universities. Among the lay non-academics were a parish director, a grant manager, a pastoral associate and the global ambassador of the Leadership Roundtable.

In other words, this was a crowd loaded with brain power, influence, episcopal authority and decision-making authority regarding the formation of future priests. It must have been a terrific discussion.

But we can't tell you much about it because reporters were banned. What we received, in lieu of being there, was a communique, available here. It won't take you long to read it. It contains about 16 paragraphs. Ten of them make up a list of "Pastoral Recommendations." The list is a skeletal representation of what was discussed over two days of meetings. It is a thin list of stated realities and wishes, self-evident and repetitious of points made repeatedly in countless forums over a lot of years. If it signifies the heart of the content, whoever funded this gathering has reason to seek a refund.

That stale set of recommendations, of course, was not the discussion. We know that. Anyone inside or outside the room where the discussions occurred knows that. The problem, of course, is that the community was shut out of knowing what precisely was said and who said it.

The organizers, theologians Thomas Groome, Richard Gaillardetz and Richard Lennan, are vital experts and thinkers within the Catholic community. They and others attending have been invaluable sources on countless occasions for NCR. They regularly help us understand events as they are occurring, providing perspective, scholarship and hard-earned wisdom. But with this event, they did the wider community no favors.

The robust discussion that occurred, they say, could not have occurred without guarantees of confidentiality. We don't buy that rationale.

One of the documents that was foundational to the earliest direction of National Catholic Reporter was a speech, "The Social Function of the Press," given by Jesuit scholar John Courtney Murray to Catholic journalists in Rome in 1963.

"The Catholic press," he said, "does not exist to further certain interests of the church merely, especially if these interests be conceived in some narrow and rather sectarian sense." It also did not exist, he said, "to glorify the clergy" nor to "create a public image of the church that will be untrue to the reality of the pilgrim church, the wayfaring church, the church that trudges along the road of history and gets her feet dusty at times, the church that has hands by which she takes hold of dirty stuff of history … because history is rather dirty stuff!"

Most important to the moment, he said: "The freedom of the press knows only one limitation, and that is the people's right to know. And I think that within the church, as with civil society, the need of the people to know is in principle unlimited."

We've operated on that principle for more than 55 years. It remains bedrock to us. That's why when a gang of influential cardinals and other members of the hierarchy, seminary rectors, academics and other such luminaries gather in a room to have closed discussions about the future direction of the church, we get deeply concerned.

What's to be afraid of? Do organizers of such meetings think the faithful could get shaken because bishops might disagree with one another? Do you buy into that old saw that "the faithful" are so dull and uninformed that they might be scandalized by new ideas, or different analysis? Don't flatter yourselves. We know you don't all think alike. We know that the church changes, even if you don't want to admit it. We know that the clerical culture is deep in a ditch of its own making.

We are aware, too, that no sunshine laws exist requiring the church and its agencies to have open meetings. We also understand that there are times when organizations will have private meetings. But the default position should be transparency. Deviating from that should be the exception and only when absolutely necessary to protect privacy. The Catholic community is today living the results of centuries of secrecy and exclusion. It's a failed model.

It is the height of irony that an academic institution should be the setting for a closed discussion that has wide implications for the future of the Catholic community. Particularly ironic during a papacy that not only is not intimidated by new ideas, but invites the friction of serious thought. Goodness, Pope Francis tolerates some of the nuttiest fringes and craziest opposition we've seen in any recent papacy, not to mention a meddlesome pope emeritus and his acolytes. Frank discussions among serious church thinkers and leaders about the abundant "dirty stuff" of recent ecclesial history would hardly cause him distress.

Given the state of things in the church, the community will need more, not less, thoughtful discussion about what's ahead. Don't be afraid to let the rest of the community in on the conversation. People have a right to know.

[Tom Roberts is NCR executive editor. His email address is troberts@ncronline.org.]