Honesty Tercero, 11, demonstrates with fellow residents their support for Annunciation House, a network of migrants shelters Feb. 23 in El Paso, Texas. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton filed a lawsuit claiming the Annunciation House "appears to be engaged in the business of human smuggling" and is threatening to terminate the nonprofit's right to operate in Texas. (AP photo/Andres Leighton)

Two news items last week brought the issue of the church-state relations to the fore: The concurring opinion of Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Tom Parker in a case involving in vitro fertilization and Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton's lawsuit against Annunciation House, a Catholic ministry to migrants.

Church-state conflicts in the U.S. are actually quite rare. Many conflicts in American life run along the fault lines between religion and politics, which is quite a different thing, but these two cases explicitly entail church-state issues.

Parker's argument has the usual citations to William Blackstone and other legal texts, but then wades into some waters you do not usually find in a court opinion. "Following Augustine, Aquinas distinguished human life from other things God made, including nonhuman life, on the ground that man was made in God's image," Parker observed. And, a little later, he quotes John Calvin:

This doctrine, however, is to be carefully observed, that no one can be injurious to his brother without wounding God himself. Were this doctrine deeply fixed in our minds, we should be much more reluctant than we are to inflict injuries.

I half expected an examination of the issue of prevenient grace?

Alabama Judicial Building, where the state supreme court meets, is seen in Montgomery Sept. 26, 2019. The Alabama Supreme Court ruled 8-1 Feb. 16, 2024, that frozen embryos qualify as children under state law. (OSV News/Reuters/Chris Aluka Berry)

Here is the thing. We Catholics believe, like Parker, that we are required "to treat every human being in accordance with the fear of a holy God who made them in His image." But the First Amendment's guarantee of religious liberty does not extend only to Christians and our theology. Whatever the good people of Alabama intended when they drafted their constitution, the U.S. Constitution can only be grasped as a religious event because it happened in the heyday of deism. Yes, Thomas Jefferson invoked the creator in the Declaration of Independence, but Jefferson's God left the world alone once he had finished his creation. The Christian God interferes in human affairs all the time.

The Texas case is also a direct attack on the First Amendment guarantee of the free exercise of religion. The good people at Annunciation House — so named at the behest of St. Mother Teresa of Kolkata — are clearly exercising their religion when they minister to migrants. What is more, although many Republicans fail to see it, without such ministries, the so-called migrant "crisis" would be even worse. No matter how suited migrants are to demagogic exploitation by former President Donald Trump and his GOP lackeys, they possess human dignity and caring for them serves the common good. The common good is not "made in the USA." It is universal.

Advertisement

The biblical injunction to care for the migrant is one of the most common in the Hebrew Scriptures. The Gospel of Matthew (2:13-23) recounts the Holy Family's flight into Egypt, that is, they were refugees fleeing persecution. The only limits to freedom of religion acknowledged in the Second Vatican Council's Declaration on Religious Freedom, Dignitatis Humanae, are violations of public order. That document states:

Provided the just demands of public order are observed, religious communities rightfully claim freedom in order that they may govern themselves according to their own norms, honor the Supreme Being in public worship, assist their members in the practice of the religious life, strengthen them by instruction, and promote institutions in which they may join together for the purpose of ordering their own lives in accordance with their religious principles (Paragraph 4).

So, why can I cite religious authorities but Parker can't? Because I am not seeking to invoke the civil power to enforce my religious views. As the council stated:

This Vatican Council likewise professes its belief that it is upon the human conscience that these obligations fall and exert their binding force. The truth cannot impose itself except by virtue of its own truth, as it makes its entrance into the mind at once quietly and with power (Paragraph 1).

Conscience, and reason, mediate religious convictions — and secular ethical convictions as well — in the context of a pluralistic society.

Let's repeat that: Conscience and reason mediate religious convictions in the context of a pluralistic society. That pluralism looked very different in 1789 from what it does today. It is not true that America is a Christian nation, but it was, for most of its history, a nation of Christians, and the dominant cultural influence through the mid-19th century was Puritanism. As Alexis de Tocqueville famously observed, "I can see the whole destiny of America contained in the first Puritan who landed on those shores." The late 18th-century Puritans who ruled the New England states at the time of the founding supported the separation of church and state not because they had abandoned their theocratic sensibilities, but because they did not want the federal government infringing on the church establishments in their states. It was not until the 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868 that the Bill of Rights, with the First Amendment's disestablishment clause, was made applicable to state law.

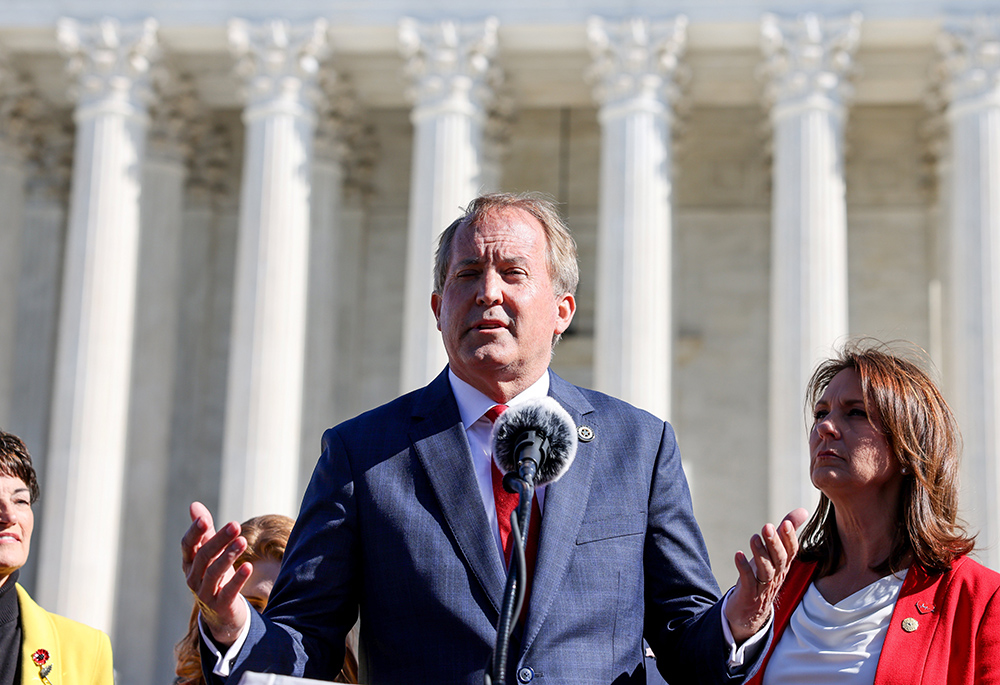

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton speaks to pro-life supporters outside the U.S. Supreme Court Washington Nov. 1, 2021, following arguments over a challenge to a Texas law that bans abortion after six weeks. (CNS/Reuters/Evelyn Hockstein)

The role of mediation was a touchpoint of the Reformation. Protestant reformers argued for the individual believer's direct access to the divine via Scripture alone. Catholics insisted on the idea that grace is mediated, through the sacraments and through the church itself. Luther famously opined, "Reason is a whore, the greatest enemy that faith has; it never comes to the aid of spiritual things, but more frequently than not struggles against the divine Word, treating with contempt all that emanates from God." It is an irony of history that Reformed Christianity proved more fertile ground for democracy in the 18th century than Catholicism, even though we Catholics possessed some of the necessary intellectual architecture to make democracy work.

Secularists, too, should acknowledge the essentially religious quality of their foundational beliefs, be they derived from John Locke or John Stuart Mill. Secular ideology, like religious belief, is rooted in philosophic claims that are not provable.

Parker is an evangelical Christian and he is free to allow his conscience to be informed by his faith. All Americans can acknowledge the formative role of Moses and Hammurabi and Maimonides in the development of our modern, Western legal culture. But only in a theocracy is it a direct route from religious influence to public policy and constitutional law. Parker and Paxton got the relationship between church and state very wrong, and no one has a greater interest in pointing that out than those of us who draw on our faith to inspire our understanding of civic responsibility.