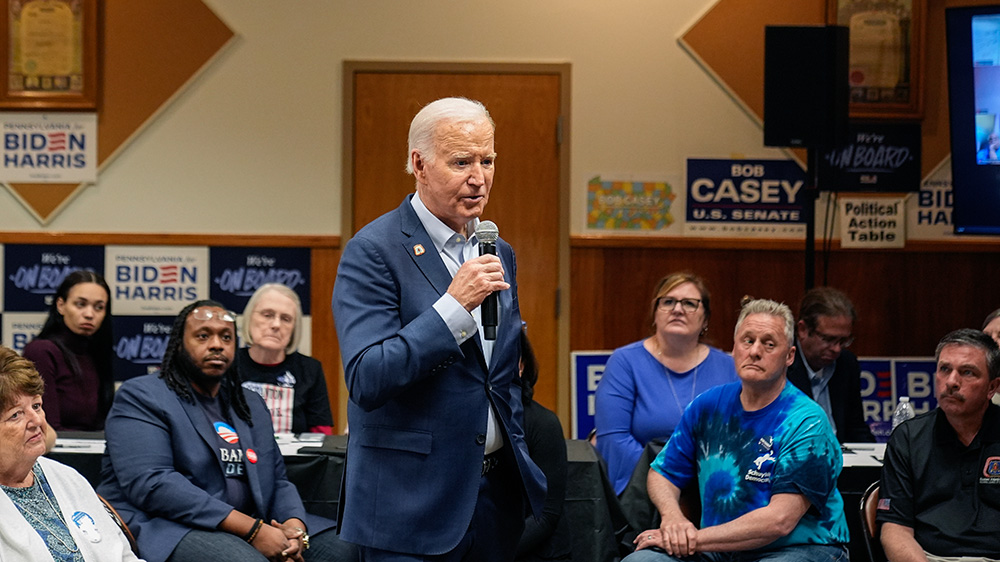

President Joe Biden speaks at the Carpenters Union Hall April 16 in Scranton, Pennsylvania. (AP/Alex Brandon)

President Joe Biden made a three-day campaign swing through the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania last week. The most important key to winning the White House for any Democrat is rebuilding the "blue wall" of states along the Great Lakes, from Pennsylvania to Minnesota, the wall that Donald Trump demolished in 2016 when he defeated Hillary Clinton in Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania.

Michelle Cottle, in The New York Times, recently spoke to key Democratic office holders, strategists and campaign workers about what it will take for Biden to win Pennsylvania. A lot of what she reported struck home, but this was this most important insight in the entire piece:

"You can't rely on the places traditionally friendly to us. You have to close the margins in places we're not going to win," said Lt. Gov. Austin Davis, a Democrat. Take the reliably red counties of Westmoreland, in the Pittsburgh region, and rural Northumberland, he offered: "You can lose 60-40, but you can't lose 70-30. It makes a huge difference." ...

Team Biden will need to build up its campaign infrastructure and outreach early in places where Democrats usually get clobbered.

This is a keen observation, one that points beyond its self-evident electoral value to a further sociopolitical fact: Going to areas that do not lean toward one's own party is healthy for the party, exposing its candidates to the concerns of people with whom they do not normally interact. In addition to the party-building value of reaching into such areas, this is the first step in overcoming polarization once the election is finished.

Advertisement

Social Service Sr. Simone Campbell, who formerly directed Network, recognized this need when she embarked on a book tour through eight southern states, which she wrote about for NCR's Global Sisters Report. One could point, as well, to her involvement with the One Country Project, where she highlights common values that have not been able to transcend divergent political framing and interests.

Reaching beyond the base was also key to Gov. Howard Dean's 50-state strategy when he took the reins at the Democratic National Committee in 2005. Dean insisted on making modest investments in party infrastructure in red states, and recruiting candidates for all levels of government.

The results were significant, as Elizabeth Daigneau explained in this article at Governing. "In the 20 states we looked at — those that have voted solidly Republican in recent presidential races — Democratic candidates chalked up modest successes, despite the difficult political terrain," she wrote. "Then, after the project stopped, Democratic success rates cratered."

The 50-state strategy not only paved the way for Barack Obama's 2008 victory in terms of strengthening the party in a red state like Nebraska, where Obama garnered one electoral vote, but it made his unifying message — "There's not a liberal America and a conservative America — there's the United States of America. There's not a black America and white America and Latino America and Asian America; there's the United States of America." — plausible.

Unfortunately, Obama's political team never much cared for the 50-state strategy. His candidacy, both in 2008 and 2012, was built, understandably, on the fact that he was a once-in-a-lifetime political star, not on door-knocking in red states.

Going to areas that do not lean toward one's own party is healthy for the party, exposing its candidates to the concerns of people with whom they do not normally interact.

Biden doesn't have Obama's magic, but he is from Scranton, Pennsylvania, and the reason for the three-day trip to the state in which he was born is to remind people that he is, in a sense, still from Scranton.

When the president is speaking in front of a labor audience, as he did in Philadelphia last September, he is at his best. It is not just that his pro-union policies have strengthened organized labor, so he can proudly tout his record. It is that he understands the dignity work confers. Losing one's job is not only an economic challenge, but an existential one, and plenty of working-class people in Pennsylvania learned what it means to lose a job in the past 40 years of neoliberal economics.

There is a reason Trump was able to win Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin in 2016: People whose lives had been upended by all the social pathologies that followed the loss of manufacturing jobs were angry. They were not wrong to direct their anger at elites: cultural elites who ignored their worries about mines and factories closing, economic elites who made trillions of dollars in the globalized economy that had left countless small cities behind, and political elites that enacted the policies that shipped the jobs overseas and then called those who were angry about being left behind "deplorables."

Biden won all three states back precisely because he is not only from Scranton, he is of Scranton. If he is to win reelection, he needs to reach out to voters in the red parts of Pennsylvania, not just the blue parts. That is not only necessary to winning in November. It is essential if he hopes to start healing a polarized nation in a second term.