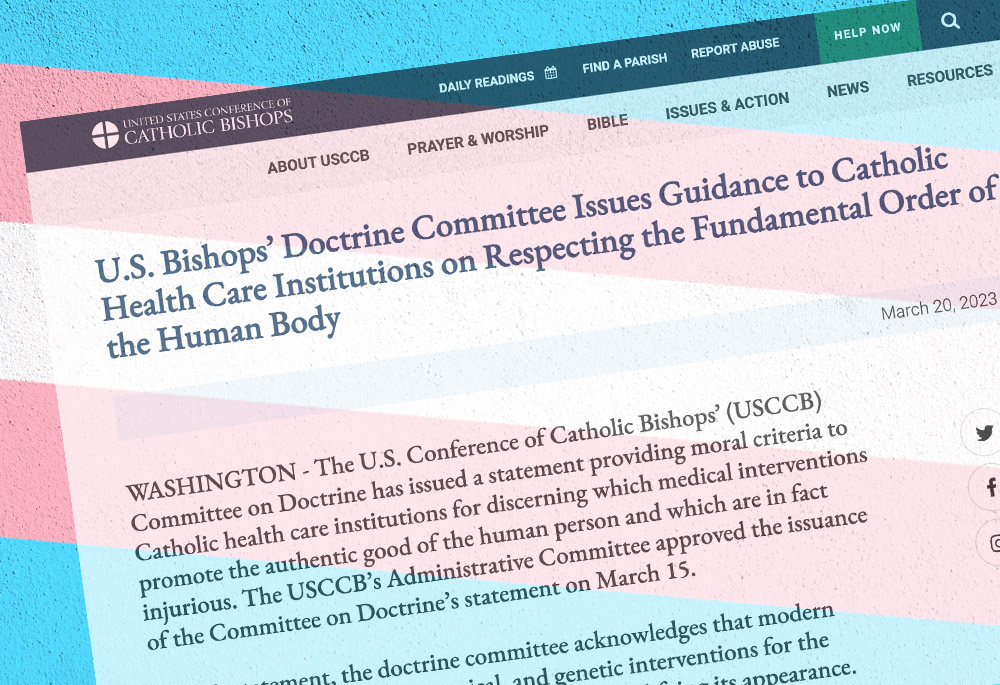

Overlay: The website of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops displays the Doctrine Committee's statement for Catholic health care institutions regarding medical treatments for transgender persons. (NCR screenshot; trans flag illustration by Dreamstime/Avictorero)

In paradise, bishops will not be permitted to speak about issues of sex and gender.

Same for the theologians.

On March 20, the Doctrine Committee of the U.S. bishops' conference issued a statement, or doctrinal note, with guidance for Catholic health care institutions regarding medical treatments for transgender persons. In a nutshell, the statement sets out reasons that Catholic health care cannot perform sex-change operations, or similar therapeutic methods, by which a person transitions from one biological sex to another.

The document poses a variety of difficulties. One bishop told me he thought it lacked pastoral sensitivity. It is somewhat unfair to fault the doctrine committee for issuing a doctrinal statement.

It is also a highly technical document. For example, Paragraph 10 deals with "the morality of interventions undertaken to improve the body not in terms of its functioning but rather in terms of its appearance, which can involve either restoring appearance or improving it." I am sure this paragraph made sense to health care experts and bioethicists, but the rest of us, armed only with common sense, were prepared to stipulate that getting a facelift is not like getting a sex change.

That said, in this day and age, and especially on a hot-button issue like this, every statement from an individual bishop or from a group of bishops should consider its pastoral consequences. Even though it was directed to health care administrators, once public, such documents reverberate throughout the church.

The document states that Catholic health care providers "must employ all appropriate resources to mitigate the suffering of those who struggle with gender incongruence," It would have cost the authors nothing to have expressed a few more words of compassion for those persons who experience some variety of gender incongruence or noted the immense challenges such persons face.

I also heard complaints that the committee did not sufficiently consult with a wider group of bishops, especially bishops who have Catholic health care institutions in their dioceses. A source familiar with the drafting process told me that the document was shaped over several years and that the committee had consulted widely with bishops and theologians. In an organization riven by serious, persistently conflicting points of view, there is almost no such thing as too much consultation.

Turning to the text itself, it exhibits a problem that has long dogged post-conciliar theology, namely, trying to weld together traditional natural law theology with Communio theology, named for the journal founded by then-Fr. Joseph Ratzinger, Fr. Hans Urs von Balthasar and Jesuit Fr. Henri de Lubac.

In areas of social teaching and ecclesiology, that welding has created a mostly seamless whole as seen in magisterial texts like Pope Benedict XVI's encyclical Caritas in Veritate, and in theological works like the late David Schindler's magnificent Heart of the World, Center of the Church: Communio Ecclesiology, Liberalism, and Liberation, which applied the Communio theology of the great Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar to a range of issues in the U.S. church.

The relationship of Communio theology's vision to Catholic morality, however, has long been difficult to parse. As I pointed out when I reviewed Schindler's book in The New Republic in 1999:

It is true that the Balthasarian moral vision is difficult to sketch. The Balthasarians tend not to focus on moral issues precisely because they are wary of reducing religion to morality. What is clear is that a Balthasarian moral scheme would be at once more radical and more reticent than any dispensation of natural law. Schindler reminds Christians that they are called to conversion, and not only to kindness, and that conversion is a lifelong struggle. Natural law inevitably issues in a practical, act-centered morality that invites a kind of spiritual minimalism. The Balthasarian vision is more psychologically astute. It recognizes that even the best of intentions are not unstained by egoism, that sin is a part of the soul.

Add to that the many and controversial uses to which Communio theologians put the concept of gender and you have plenty of room for criticism.

Protesters hold signs as they chant for and against a bill that would make Minnesota a trans refuge state, and strengthen protections for kids and their families who come to the state for gender-affirming care, outside the room where lawmakers would vote on the bill at the state capitol March 23 in St. Paul. The Minnesota House passed the bill early the next morning. (AP/Trisha Ahmed)

The biggest practical problem with the document is that the hyper-teleology of the natural law, combined with a rigorous understanding of the call to conversion in the Gospels, yields an understanding of sexual morality that permits no exceptions and lacks all nuance. The realization that, for a small but definite percentage of the population, sexual identity is both experienced as constitutional, that is, not as something chosen, and falls outside the moral norms that emerged in the history of the church prohibiting sexual deviations, challenges that traditional natural law understanding of sexual morality.

How we overcome this problem is above my paygrade, but I think any honest prelate must admit that the church's teaching on sexuality is inadequate as it currently stands.

There are no issues on which the views of the hierarchy and the views of theologians are at greater variance than the issues of sexuality and gender. So, it was not surprising that some progressive avatars in the theological community rushed to criticize the document.

My colleague Fr. Dan Horan, the director of the Center for Spirituality and professor of philosophy, religious studies and theology at St. Mary's College in Notre Dame, Indiana, wrote that the document was "nothing short of a disaster: theologically, scientifically and pastorally."

People attend a rally in support of transgender rights in Los Angeles Oct. 20, 2021. (CNS/Reuters/Mario Anzuoni)

Horan's approach to the topic is emblematic of the approach many progressive theologians take to neuralgic issues of race, gender and sex. For example, NCR readers will be familiar with the writings of Creighton University's Michael Lawler and Todd Salzman, who follow a similar approach. Start by citing works that deconstruct the tradition. Craft a narrative rooted in the exclusive identity of a group or groups, with heavy emphasis on their self-reported claims, and aiming at an ethic of liberation.

Whatever you think of the approach, and I think it has significant limits, in this case Horan fails to recognize one major problem with his criticism: He wants the bishops to articulate what the church does not teach. He quotes Pope Francis about wanting a culture of encounter, but ignores the Holy Father's warnings about gender ideology.

The U.K. National Health Service did not rely on the U.S. bishops in making its decision to close down the Tavistock Gender Identity Development Service. It relied on a report indicating that the risks of providing such care had not been adequately studied. "Any potential benefits of gender-affirming hormones must be weighed against the largely unknown long-term safety profile of these treatments in children and adolescents with gender dysphoria," the NHS report said.

Hannah Barnes, who led the BBC investigation into the Tavistock Centre, explained in a WBUR interview that one of the principal difficulties was "diagnostic overshadowing" in which "a young person who may have multiple coexisting difficulties but who had gender related difficulties as well, once the word gender was mentioned, everything else got parked, if you like, it wasn't dealt with."

Advertisement

Studies have only just begun to analyze the links between gender dysphoria and autism, for example. So, if we are going to look at the science, we need to look at all of it, not just the parts that conform to gender ideology already arrived at.

There is much more to be said about transgender issues and the Catholic Church. Returning to the bishops' document, I wish to make two recommendations, one small and particular and the other large and expansive.

First, I wish Catholic leaders, in the hierarchy and the academy, would adopt the phrase, "That is not in our tradition," rather than rushing to denounce something or some idea as "sinful" or "harmful." The tradition develops, and it needs self-critical analysis to do so, and the use of fraught language only makes people dig in. What does and does not constitute "harm" is the heart of the debate, so hurling it at the other side only obfuscates, it does not clarify, the issues. The recent statement and video from the Scandinavian bishops did a much better job of setting forth the church's teaching without bashing anyone.

The larger or prior problem is that we U.S. Catholics need to find ways to stop reducing religion to ethics, whether those ethics be conservative or liberationist. Our ethical teaching, especially in the area of human sexuality, can't stand on its own, but it was never meant to stand on its own.

We need continually to redraw the links to the Christian anthropology from which our ethical claims grow, and redraw how our anthropology is rooted in our Christology. If we place sexual teachings at the forefront of our evangelizing efforts, we will become complicit in the effort to turn the church into an upper-middle-class club for people with conservative, or liberal, sexual ethics.

As one bishop said to me recently, "We need to introduce people to Jesus before we start talking to them about sex." Amen.