Pope Francis leads a meeting with representatives of bishops' conferences from around the world at the Vatican Oct. 9, 2021, before launching the process leading up to the first assembly of the world Synod of Bishops in 2023. (CNS/Paul Haring)

At chanceries and rectories across the land, The Synodal Process Is a Pandora's Box: 100 Questions and Answers, is arriving with the obvious goal of seeking to undermine the synodal process Pope Francis has begun. I was surprised they did not stop at 95 and nail the text to the doors of St. Peter's.

My colleague Christopher White, NCR Vatican correspondent, explained the source of the volume on Monday. The book is published by Tradition, Family and Property, a reactionary group that started in Brazil in 1960, and distinguished itself for opposition to Vatican II and affinity for right-wing juntas.

Unsurprisingly, the authors managed to get a pearl-clutching forward to the volume from American Cardinal Raymond Burke, a tragicomic figure in today's church, wrapped in watered silk and wistful nostalgia for a church that never existed outside his imagination.

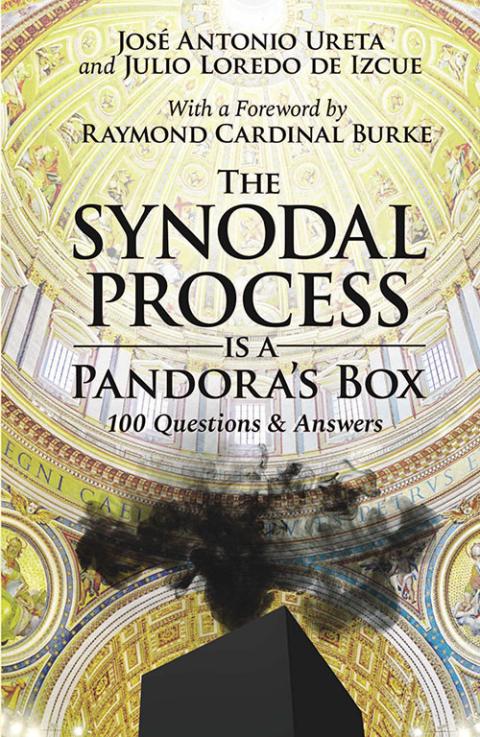

The cover of The Synodal Process Is a Pandora's Box, released in late August by the group Tradition, Family, and Property (CNS/Courtesy of the CC)

Although two members of Tradition, Family and Property are listed as the authors, most of the book consists largely of quotes from others:

- Fr. Michael Nazir-Ali, former Anglican bishop of Rochester, England, and now a Catholic priest;

- Gavin Ashenden, also a former Anglican cleric;

- Edward Pentin, Vatican correspondent for EWTN's National Catholic Register;

- Fr. Gerald Murray, a priest of the New York Archdiocese who is a regular guest on EWTN's "The World Over with Raymond Arroyo";

- Jayd Henricks, former top lobbyist for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and now director of the group Catholic Clergy and Laity for Renewal, which mines cellphone data to ensnare priests who use morally problematic websites;

- Carl Olson, the editor of the Catholic World Report, published by conservative Ignatius Press;

- Bishop Robert Mutsaerts, an auxiliary of the Dutch Diocese of 's-Hertogenbosch who has already resigned most of his administrative functions because of disagreements with his ordinary.

The list demonstrates something that has been obvious for some time: The opposition to Francis is located mostly in the Anglosphere and evidences all the defensiveness that emerged among some Catholics who grew up in a non-Catholic culture. There are others, such as Sandro Magister, but most of the citations to opinions and criticisms are from English speakers.

I am no scholar, and I do not pretend to be one, but it is also worth noting that none of the men who are quoted has distinguished himself for any expertise in Catholic theology.

I love converts as much as anybody, but I admit I find it odd that Nazir-Ali and Ashenden could live most of their adult lives out of communion with the bishop of Rome, accepting promotions and preferments in a communion with a very different ecclesiology, then swim the Tiber and declare themselves more Catholic than the pope.

From left: Cardinal Raymond Burke (CNS/Paul Haring); Former Anglican Bishop, now Fr., Michael Nazir-Ali (CNS/Courtesy of Michael Nazir-Ali); Fr. Gerald Murray (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Pentin and Murray are typical EWTN shills for a peculiar type of conservative Christianity, and Olson's online journal is reliably reactionary. I know nothing about Mutsaerts except that his devotion to the Tridentine liturgical rites seem to have placed him in opposition to Francis.

What does the book say? In a word, nonsense. In a phrase, dated nonsense.

It asks: "Can a Pope or Synod of Bishops Change the Catholic Church's Doctrine or Structures?" And the reply could have been written in 1870. "No. Neither the pope, the Synod of Bishops, nor any other ecclesiastical or secular body has the authority to change the doctrine or structures of the Church, set and entrusted in deposit by her divine Founder." The citation that follows is from the First Vatican Council.

Now, I love the First Vatican Council as much as the next Catholic, and I especially enjoyed reviewing the late John Quinn's masterful book Revered and Reviled: A Re-examination of Vatican Council I. But unless you are familiar with the ideological ferment of the times, it is hard to cut-copy-paste a quote from Vatican I and plunk it into a discussion of the church in the 21st century without doing violence to history and theology.

Gavin Ashenden (left), a former Anglican bishop, is pictured with Bishop Mark Davies of Shrewsbury, England, following Ashenden's reception into the Catholic faith Dec. 19, 2019. (CNS/Simon Caldwell)

Sometimes, the problem is not historical derangement but an inability to assume the good faith of the pope, combined with a bizarre need to exhibit the author's own fears. For example, the question is posed: "What Is Behind the 'Inclusion' Proposal?" The text quotes from Ashenden:

The words trick is easily explained. The association with being excluded is being unloved. Since God is love, he obviously doesn't want anyone to experience being unloved and therefore excluded; ergo God, who is Love, must be in favor of radical inclusion. Consequently, the language of hell and judgment in the New Testament must be some form of aberrational hyperbole which must not be taken seriously, because the idea of God as inclusive love takes precedence. And since these two concepts are mutually contradictory, one of them has to go. Inclusion stays, judgment and hell go. Which is another way of saying, "Jesus goes, and Marx stays."

This is then applied to overturn all the Church's dogmatic and ethical teaching.

Wow. I suppose that is one way to interpret the preparatory documents. To me, the call to inclusion merely meant that we shouldn't place unnecessary hurdles in front of the doors to the church.

Some questions are so leading, even passive-aggressive, you do not need to wait for the answer. For example: "24. Do Synod Promoters Distinguish Between the Active Role of the Magisterium and the Passive Role of the Faithful in the Organic Development of the Deposit of Faith?" and "59. Are There Any Ulterior Motives Behind the Synodaler Weg?" These are the ecclesial equivalent of an aggrieved parent asking a teenage child, "So, is that what we're wearing today?"

There is concern that prelates who raise difficult questions in good faith should be punished for disturbing the gentle consciences of the troglodytes.

Advertisement

"For example, the absence of any reprimand from Vatican authorities to Cardinal Robert McElroy for his scandalous article in the Jesuit magazine America is striking," the book states. "For his part, Cardinal [Jean-Claude] Hollerich was confirmed in the decisive role of relator general of the Synod even after his scandalous statements on the need to change the Church's magisterium on homosexuality."

Now, I disagreed with parts of McElroy's America article and I think Hollerich does not acknowledge how difficult it will be to change the church's teaching on homosexuality. But "scandalous"? Methinks these opponents of the synod are too easily scandalized. It is not clear why homosexuality seems usually to be the source of their most perfervid fears.

It is a little surprising that the authors turned to Greek mythology for the title of this work. They evidently could not find anything in the sacred Scriptures nor in magisterial teaching to encapsulate their fears. It is a thing worth noting.

This book-length, prophylactic attack on the synod is not alone. At Catholic Culture, Phil Lawler has sounded the alarm and in a similar way. Here is the way he introduces a thought experiment: "Imagine that somehow an avowed heretic won election to the papacy." This, and what follows, bears no resemblance to anything Francis has done or plans to do.

Lawler's column, like the Tradition, Family and Property book, is meant to cripple the synod. They are not shy about casting aspersions on the Holy Father and his character to do it.

From left: Carl Olson (CNS/Courtesy of Catholic World Report); Auxiliary Bishop Robert Mutsaerts of 's-Hertogenbosch, Netherlands (Wikimedia Commons/Danny Gerrits); Jayd Henricks (CNS/Bob Roller)

These critics should remember Canon 1373: "A person who publicly incites hatred or animosity against the Apostolic See or the Ordinary because of some act of ecclesiastical office or duty, or who provokes disobedience against them, is to be punished by interdict or other just penalties."

Could the synod miscarry? I hope not. And I do not think it will. Francis was not afraid to refuse the recommendation from the Amazon synod to ordain older men of proven virtue, the viri probati, because the proposal garnered a majority but did not reflect a synodal consensus. I do not see anything in any one of his writings to suggest Francis is planning on overturning our foundational doctrines.

If the church becomes more evangelical and less rigid, more engaged and less detached, isn't that a good thing, no matter what the synodal process determines about any particular issue?

These prebuttals, however, are coming out not because the authors think synodality will fail. They are terrified it will succeed. These right-wing extremists are recognizing that most Catholics love Francis, even in the Anglosphere. They know, deep down, that people are not confused by his fixation on God's tender mercy. They know, deep down, that none of us should judge our brothers and sisters who struggle. They know that when leadership is less remote, horrible crimes like the cover-up of clergy sex abuse are less likely to occur.

They are upset because they are the kind of people who are only happy when they are upset, only content when they are looking down on others, heresy hunters who have peered through the world so long with only one kind of lens, they can no longer distinguish reality from their glasses. They are Javert and they resent anyone getting in the way of their pursuit of a twisted sense of divine retribution. They are not to be listened to, but to be pitied.