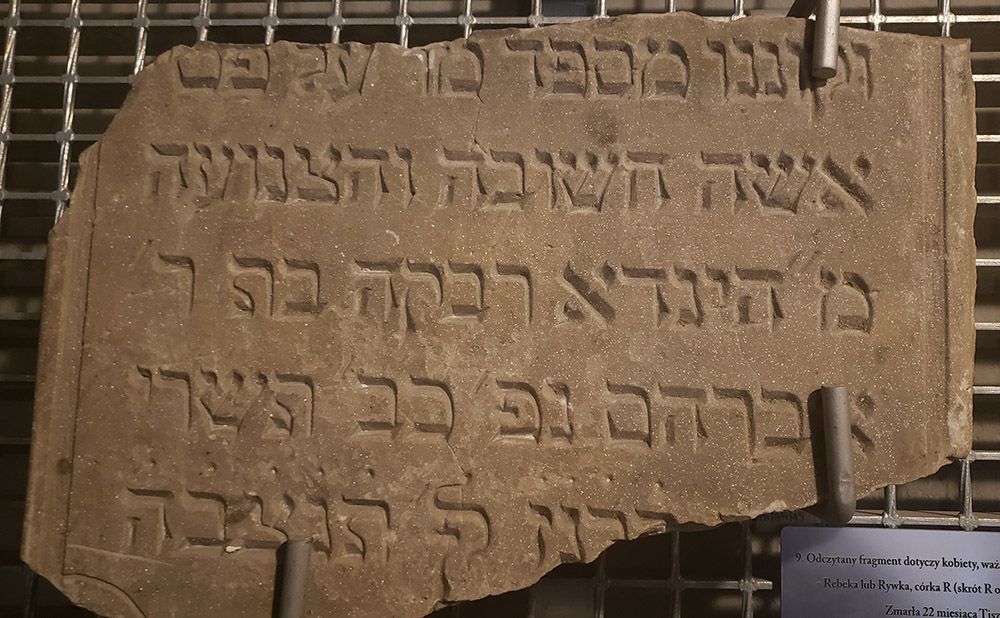

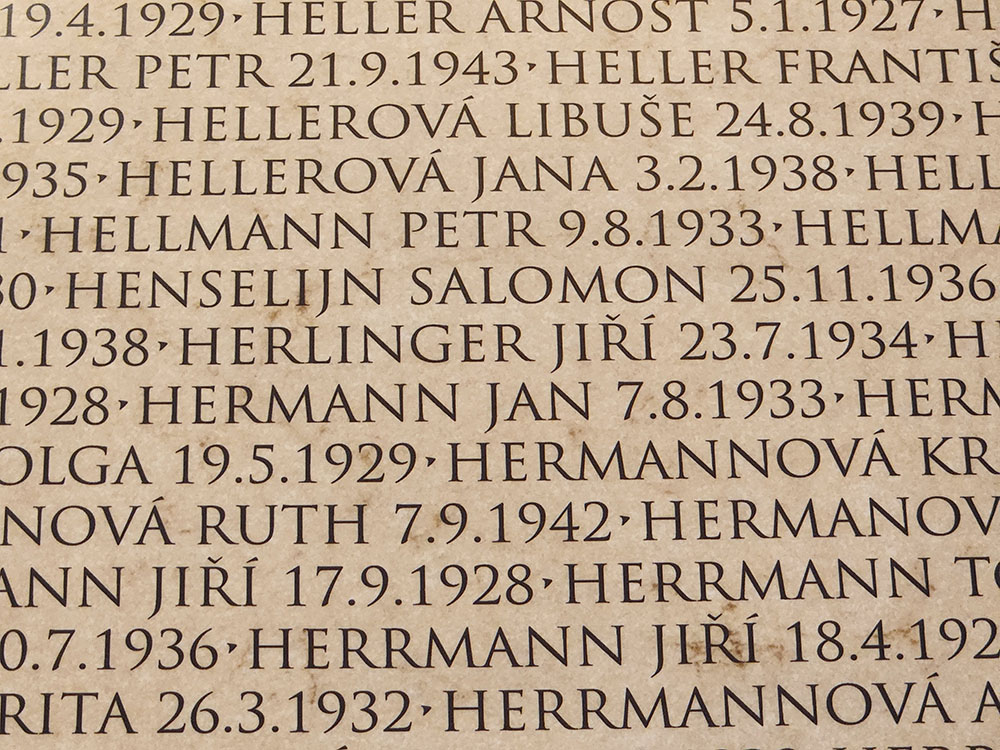

At a museum in Terezín, Czech Republic, a wall bearing names of child victims who were deported from the ghetto to death camps includes the name Jiří Herlinger. (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

What if memory is thwarted? What if memory is extinguished? What if the state wants memory erased?

Temporal powers often threaten memory — something we in the Jewish and Christian traditions know from recent Holy Days and was made vivid to me during assignments to Europe to cover the humanitarian effects of war, both in Ukraine and neighboring Poland.

It is a region that historian Timothy Snyder calls the bloodlands, the vast area between Germany and the Soviet Union where, from 1933 to 1945, 14 million civilians were murdered.

I am keenly aware of that history — in the shadow of the war in Ukraine, my travels have allowed me to make side trips to more than a half dozen Holocaust memorial camps or ghettos in the last 13 months.

Nearly a year ago, on Good Friday 2022, I wrote about my experience at Auschwitz-Birkenau as I began a reporting assignment in Poland. I noted that the enormity of Auschwitz is hard to minimize. Contemplating the murder of 1.5 million victims there "weighs heavily on visitors, and the mind seeks answers," I wrote.

Since then, I have visited memorial sites in Dachau, Germany; Treblinka and Bełżec in Poland; and Theresienstadt in the Czech Republic. In Kyiv, Ukraine, I visited the Babi Yar memorial site, where nearly 35,000 Jewish Ukrainians were executed over two days in September 1941.

I visited the Neuengamme Concentration Camp memorial near Hamburg while on a personal trip to Germany in February 2022, prior to the war. I also journeyed last November to the Museum of the History of Polish Jews where the Warsaw Ghetto once stood. And to complete the loop, in a sense, I visited the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., in March.

How to describe the weight of those experiences? Calling them searing, shattering and disturbing hardly does them justice. But why the need to visit? Some may ask: Isn't it enough to cover events in Ukraine and Poland? Isn't visiting one death camp memorial sufficient? (Some friends have almost implied, "Are you OK?")

Advertisement

I don't have a ready answer — it is still a bit of a mystery even to myself. Maybe it is the need to bear witness; an act of pilgrimage and solidarity; interest as a lifelong student of history and of the Holocaust in particular. (I still recall seeing my first clip of a Holocaust newsreel when I was a Denver junior high school student.)

Or maybe it is due to an event in my mid-20s: While working my first newspaper job in rural Minnesota, I drove three hours to Minneapolis to watch Claude Lanzmann's landmark nine-hour documentary film "Shoah" in a single sitting — and returned home that same night. That experience made for a very long day. But "Shoah" grabbed something inside of me and has not let go. (I should add that a good deal of the film focused on Treblinka, possibly planting a seed.)

Perhaps all of these experiences were groundings for something more personal.

My family is not Jewish — I come from a mixed Pennsylvania-bred heritage of German-Irish Catholic on my father's side and Scottish-Welsh Protestant on my mother's. But the ancestry of my paternal grandfather — the Herlinger side — is a bit murky beyond several immediate generations. There may be a distant Jewish connection there — nearly every other Herlinger I have met or know of is Jewish. Herlinger seems to be a common Jewish name.*

Sadly, though, some cursory investigating online shows a number of Herlingers perished in the Holocaust. One was a well-known Czech writer, Ilse Weber (née Herlinger), who wrote an acclaimed collection of stories in German. She died at Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1944 after being deported from Theresienstadt.

A less public figure was another victim, Robert Herlinger (1899-1942?), who lived in Prague and, who based on an image online, bore a slight resemblance to my paternal grandfather. He was deported to Theresienstadt in April 1942 and was subsequently transported to Zamość, Poland, where he was murdered.

As it turns out, Theresienstadt, or Terezín, the Czech name — site of a notorious ghetto, prison camp and transit site — proved to be a crucial locus in my Holocaust journey, and not only because of what I knew of Robert Herlinger and Ilse Weber. In February, while visiting the memorial museum at Theresienstadt, I stood in front of a wall bearing names of child victims who were deported from the ghetto to death camps.

There, I saw the name Jiří Herlinger.

While not totally surprised by this discovery, it was still something of a gut punch. From available online information I later discovered that Jiří Herlinger, too, was Czech and was deported to Treblinka in October 1942. He was 8 years old. There is no available photograph of the boy.

The detail about young Jiří's transport to Treblinka stood out for me because my November visit to Treblinka was memorable in unexpected ways, partly in contrast to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

A quiet but imposing forest at the Treblinka memorial site in Poland (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Auschwitz is a destination of pilgrimage and curiosity and, yes, tourism that hundreds of thousands visit annually. But when I visited Treblinka — about a 90-minute drive from Warsaw — my guide and I were nearly the only ones there. A fresh blanket of snow had just covered the memorial site, and we stood surrounded by a quiet but imposing forest where a barely perceptible cold wind stirred, the trees rustling, as if hiding old secrets.

The contrast with Auschwitz-Birkenau was obvious. Though the fleeing Germans tried to destroy much of the most damning evidence at Auschwitz-Birkenau — like the crematoria — enough remained intact to make clear the enormity of what had happened there. There were also enough survivors of Auschwitz to keep testimony and memory alive.

By contrast, Treblinka, where as many as 900,000 Jews were murdered, was leveled not long after a prisoner revolt. Evidence of what happened there was harder to piece together initially: There were few Treblinka survivors.

The Treblinka dead are honored with jagged, abstract monuments — piercingly and poignantly moving, I have to say. Yet except in rare exceptions, the Jewish victims — like Jiří Herlinger — remain anonymous. Their ashes and remains were buried in mass graves near the quiet woods where I had stood.

But dozens of non-Jewish Polish prisoners, presumably Catholic and also murdered at Treblinka, are named individually on crosses at a cemetery site. This surprised me — though I know there have been controversies about how best to memorialize Jewish and non-Jewish victims of the death camps. In the case of Treblinka, critics say the Polish government is engaging in "Holocaust revisionism" by overemphasizing Polish suffering and heroism.

I am not qualified to weigh in on those controversies — I was moved by everything I saw and experienced at Treblinka. But the sheer scale of Jewish loss and death can never be overstated. And a mile-long road linking a prison-labor camp and the mass execution site where trainloads of Jewish deportees were sent immediately to their death points to something crucial.

This road — now more like a hiker's trail — was once paved with pillaged Jewish tombstones, or matzevahs, from nearby cemeteries. Some of those tombstones are now displayed at the memorial's small museum.

Using Jewish tombstones like this was common Nazi practice, not just at Treblinka. But it was a shattering example of a system fully bent on denying Jews and Jewish culture and tradition writ large the final thread of dignity.

The Bełżec camp — located in eastern Poland, not far from the border with Ukraine — was similarly brutal.

Visitors to the Bełżec death camp memorial in Poland approach it through a narrow 200-yard path, walking toward the area where the gas chambers stood, trapped on both sides by steep inclines. (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

In terms of numbers of victims, Bełżec was the third-deadliest camp after Auschwitz-Birkenau and Treblinka. Yet Bełżec is little-known outside of Poland — in fact, it doesn't seem to be that well-known within Poland — because it only had a handful of survivors, perhaps no more than three.

Bełżec was extraordinary for the sheer amount of killing done in a short time. The deportation of Jews to Bełżec began in early 1942. In a 10-month period, some 450,000 Jews were murdered there. By the beginning of 1943, much of Polish Jewry had been annihilated.

What is Bełżec like? Visitors approach the memorial through a narrow 200-yard path, walking toward the area where the gas chambers stood, trapped on both sides by steep inclines. It is as if entering a baleful valley of death. ("It's like a horror movie," one of my travel companions said.)

Once there, visitors stand at a 60-foot-high wall with an engraving, in English, Hebrew and Polish, of Job 16:18: "Earth, do not cover my blood; let there be no resting place for my outcry!"

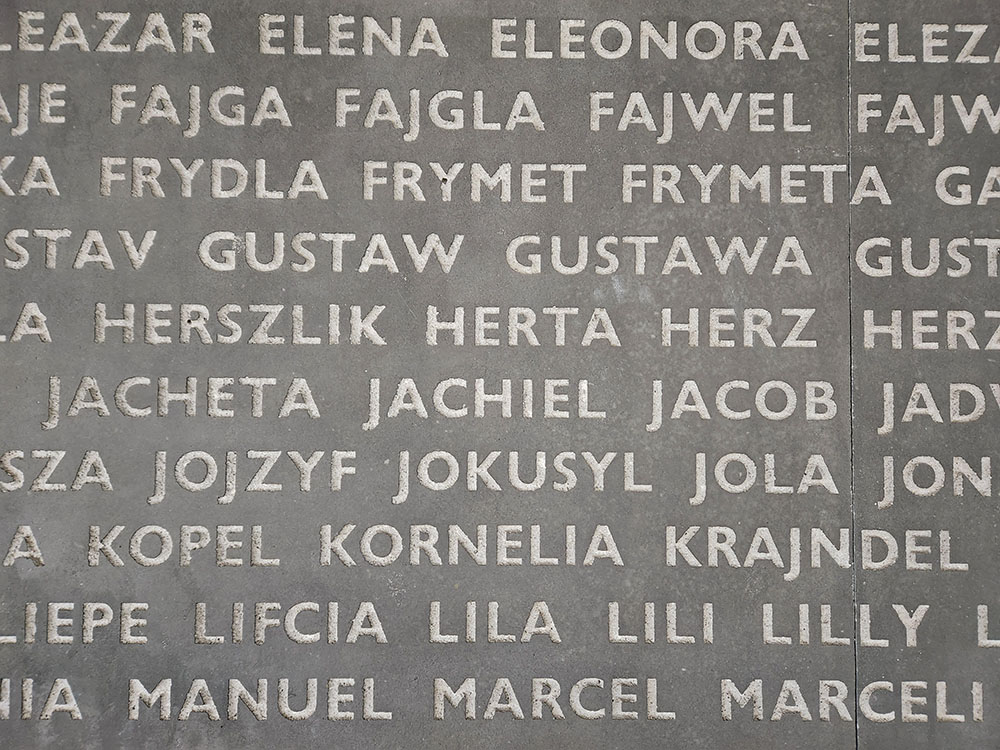

On the other side is a wall of given names — popular given Jewish names of the time; no family names are presented. The world awaits a full accounting of the victims of Bełżec.

The anonymity and loss are chilling. But that was the very point of the Nazi system.

"Earth, do not cover my blood; let there be no resting place for my outcry!"

How to make sense of all of this, particularly with the eruption of another European war?

First is that we — I mean we human beings living today — are not done with the Holocaust. Or rather, the Holocaust is not done with us. In his recent book, The Holocaust: An Unfinished History, British historian Dan Stone argues that commemorating the Holocaust is insufficient alone "to change the ways in which fascism is interwoven into the deep memory of Western culture." Stone quotes Hannah Arendt to deepen the point: Perhaps, she said, "the Holocaust was an attempt to eradicate the very concept of the human being."

Think of that — not only murdering humans, but eradicating what it means to be human: the Final Eradication.

What have I learned from these experiences? I recognize there is only so much I can do, as one individual, to counter the nihilistic and cynical turn toward anonymity and death. As we know from Ukraine and other locales on Earth, that bend still curls in our souls.

But I will do what I can to counter ever-present political threats. And in the spirit of the Jewish and Christian religious traditions that keep memory alive, I will honor and mourn the Holocaust victims with whom I share a family name.

*This sentence was updated on May 3 to include a clarification from the author.