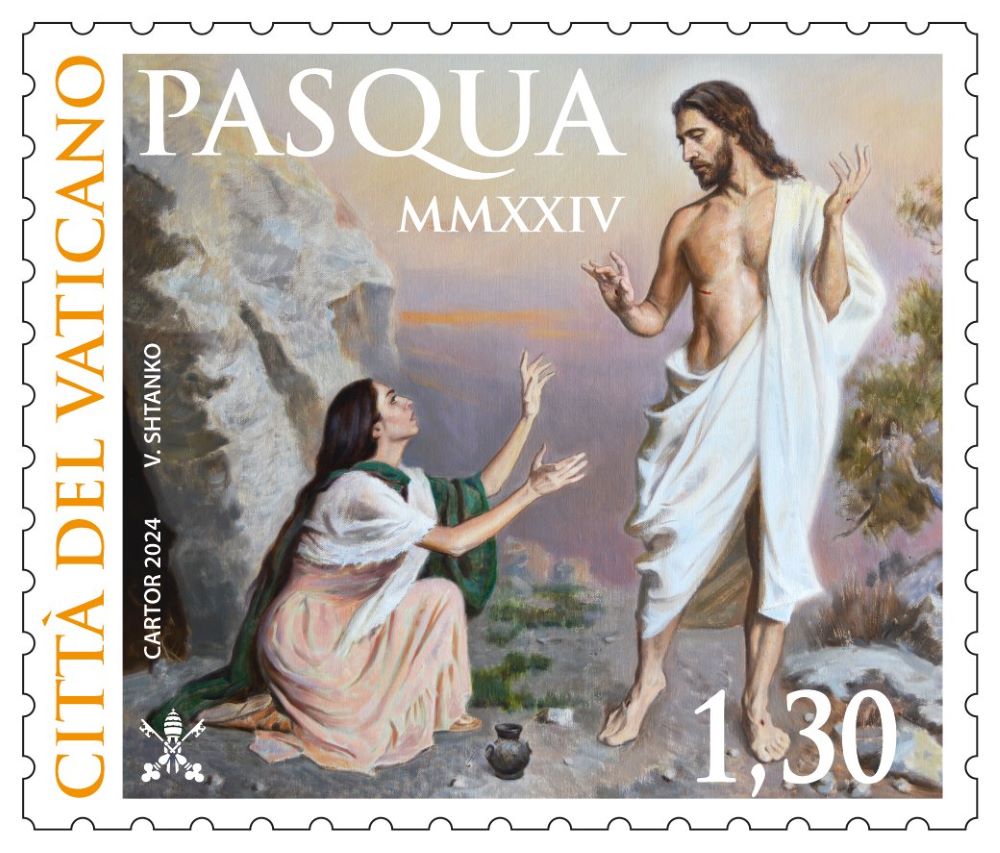

The Vatican's 2024 Easter stamp features a painting depicting the Risen Lord appearing to Mary Magdalene outside the tomb as recounted in John 20:11-18. The painting is by Ukraine-born artist Vitaliy Shtanko. (CNS/Courtesy of the Vatican Philatelic and Numismatic Office)

On Monday, following the lead of Fr. Hans Küng, we looked at the decisive character of the resurrection of Jesus Christ, and how that experience of the resurrection changed the very character of the church that followed.

Küng asks: "How did [Jesus' followers] come to proclaim, therefore, not only the Gospel of Jesus, but Jesus himself as the Gospel, unintentionally turning the proclaimer himself into the content of the proclamation, the message of the kingdom of God into the message of Jesus as the Christ of God?" The early church does not proclaim Jesus to be the great teacher, an ethical expert whose wisdom must be shared. They proclaim him to be the Messiah, "Christ crucified, a stumbling block to the Jews and foolishness to the Gentiles" (1 Corinthians 1:23). His teachings must be followed not because they are wise or not, but because they have divine sanction.

Of course, the early church had to recall his ethical teachings and embody them in their lives, but the starting point was this God-man Jesus who had been raised from the dead. "If then you were raised with Christ, seek what is above, where Christ is seated at the right hand of God," St. Paul told the Colossians in the second reading on Easter Sunday. "Think of what is above, not of what is on earth."

Christianity was not then, and is not today, primarily an ethical system. The Resurrection did, however, impart a worldview to the early Christian community, and fidelity to that worldview remains a hallmark of the Catholic Church. Indeed, all the ethical teachings of the church are downstream from this worldview born of the empty tomb.

The reduction of religion to ethics is one of the most pervasive, and destructive, realities of religious life in the U.S.

The first, most obvious, aspect of the Easter worldview is the priority of grace. No human "earned" the salvation wrought by Jesus and no human could even conceive of such a story of pain, suffering, rejection and death, followed by a completely surprising event in which God overturns the worldly condemnation of Jesus. The Resurrection is entirely God's work and our human contribution to the passion, death and Resurrection of Jesus was all shame: betrayal denial, false arrest, calling for his crucifixion, washing hands of responsibility, cruel infliction of pain and death. That was the human contribution to the narrative of our salvation.

The second aspect of the Easter worldview is the valuation of life over death. Last month, I criticized Pope Francis' remarks about the war in Ukraine, but as I noted in that column, the pope must witness to peace, to the preservation of human life, in speaking about war, not only to the evident justice of Ukraine's right to self-defense. Indeed, life has a prior claim in the Christian tradition, ahead of justice, because of this Easter worldview.

Similarly, the opposition of the early church to abortion, which was not uncommon in Jesus' time, is rooted in this Easter worldview. The reason Catholics sound not only wrong but foolish when they ignore the dignity of human life, is not because of our ethics but because of our Easter. Catholics for Choice erasing the dignity of human life in the womb, just like the state of Texas ordering its state police to deny water to migrants suffering dehydration during extreme heat, are examples of pulling death from the jaws of life. That is not a Catholic project. Our Easter Gospels tell us God brings life out of death. The contradictions are deeper than ethics. They strike at the heart of our belief about God's action at Easter.

Finally, the Easter Gospels impart a third, less obvious, contribution to the worldview of the early church and, just so, to us today: universality. A human life is an exercise in particularity: Jesus was a Jew, born in Bethlehem, raised in Nazareth, took up his father's trade, etc. Death, however, is universal. Death and taxes, right? And Jesus overcomes death "once and for all" (Hebrews 7:27). Jesus' death is the "death of death, and hell's destruction" as we sing in the great Welsh hymn "Guide Me O Thou Great Jehovah."

Advertisement

The implications of the universality of Jesus' resurrection are many and all of them profound. The individual Christian must be allergic to any variety of libertarianism because while we believe every human person has an inherent and indelible dignity, that dignity is shared with all other human persons, and society is not an intellectual construct but an existential fact of life, ordained by God. Conversely, at a time when our culture is drowning in notions of group identity, no group identity can escape the reach of grace. Grace transcends all human boundaries of race or ethnicity, of class or wealth, of gender or sexuality, of political or ideological affiliation. Jesus, in short, defeats not only death but Hayek and Herder, too!

The reduction of religion to ethics is one of the most pervasive, and destructive, realities of religious life in the U.S. The celebration of Easter presents us with a fact, the empty tomb. From that historical fact, a worldview emerges with distinctive qualities that cannot be denied or marginalized without distorting all that follows in the life of the church. Christian ethics flows from that worldview, not the other way round. If Easter is decisive, our ethical understandings necessarily must embody the priority of grace, life and universality. If not, we may be doing ethics, but Easter is no longer decisive.