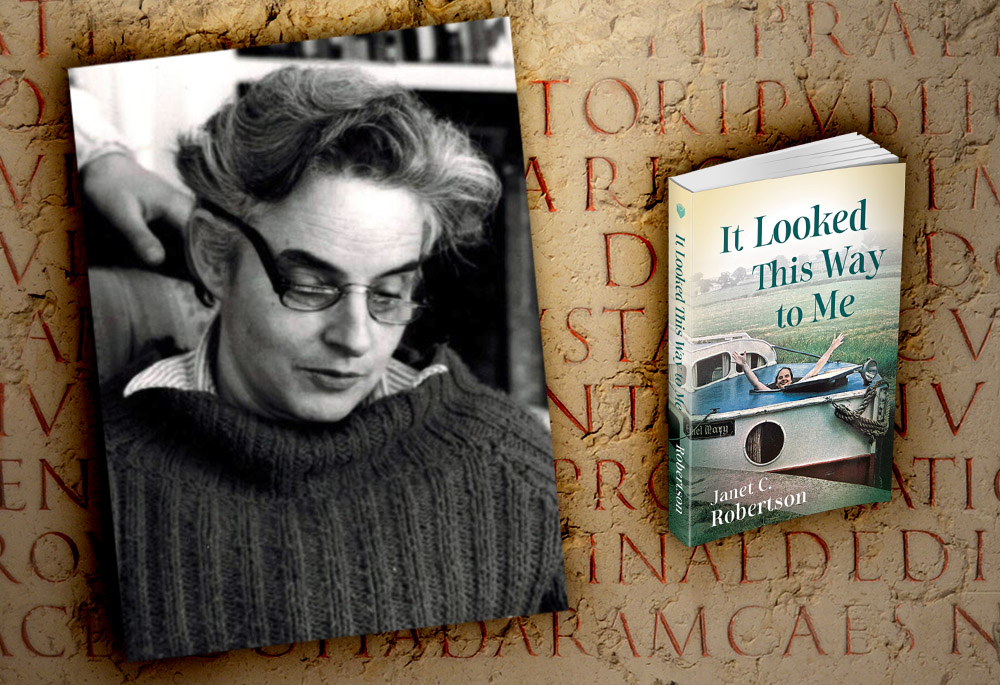

Janet Robertson and her memoir, It Looked This Way to Me (Courtesy of Luminare Press; background photo: Wikimedia Commons/Arnaud Fafournoux)

Memoirs have mostly become exercises in celebrity self-justification, a way for a politician to provide a first attempt at writing the history of his or her time, or for a celebrity to overcome bad press.

Janet Robertson's It Looked This Way to Me is not that kind of memoir. It is one of a growing number of memoirs published by non-celebrities, which is not the same thing as ordinary persons. Ordinary people do not undertake the arduous work of publishing a book. Additionally, the author may not have become famous but she is quite extraordinary.

I know this because she changed my life. "Mrs. Robertson" was my high school Latin teacher. The small, public high school I attended in rural Connecticut offered French and Spanish, but not Latin. Robertson gave lessons in her home. In addition to Latin, I learned about English grammar and Roman history and so much more sitting at the table in her kitchen. It was at that table and under her tutelage that I first learned that scholarship and history opened doors to excitement as well as enrichment.

The Robertsons were one of the few Jewish families in our WASP-y town. I knew that her Jewishness was important to Mrs. Robertson, but in the first few pages she explains just how important it is.

"There was a game I used to play. If you were awakened suddenly in the middle of the night by someone who demanded, 'What are you?' and you had to answer instantaneously, what would you say?" she asks. " 'A woman,' or 'A man,' answered some who played it with me. 'An American,' answered others. I would say, without a second's hesitation, 'A Jew.' So there you are. That is who I am."

Robertson's willingness to share the struggles as well as the joys of her life make for a compelling and a consoling read.

She details her childhood growing up in New York in the 1930s and '40s, something we never discussed at that table in her kitchen. Much of it was unhappy and Robertson recounts all the unpleasantnesses with candor and a vivid memory. She was not yet 4 years old when her father had his first heart attack.

"My mother was beside herself. She got it together enough to tell me that if I made noise or yelled or did anything to upset my father, he could die. I could kill him. I wasn't quite 4 years old in that summer of 1937 when I learned that by being bad I could kill my daddy."

Robertson's mother, Fannie Cohen, would call her only child "ugly" and "fat" and "stupid." Later in the book, Robertson notes, "My mother was always a very mean lady." It was not an idyllic childhood.

The book gets a bit confusing as Robertson recounts her childhood memories of her relatives. One passage about her grandfather, however, explains a lot: "My grandfather had a complete set of holy books, a shas, not just the complete Bible, but all the Talmud, that he studied on Saturday afternoons and whenever he got the chance," she recalls. "Somehow, he conveyed to me that to read and to learn were the best things in life. I never forgot that lesson."

Indeed, she not only remembered it; she passed it on.

Robertson went to Radcliffe and recounts her early exposure to, and excitement about, various courses of study. It was there that she met her future husband, James Robertson, who was studying at Harvard. It was not an auspicious start: He was three hours late for their first date! But a true love was born. "I have no idea where we went on that first date, only that we talked non-stop," she recalls.

Advertisement

It is in these stories of meeting Jim, while she was still pursuing her own studies, that a persistent undercurrent of the memoir emerges: It was expected at that time that women, no matter how smart, would defer to the career ambitions of their husbands. She mentions that she did not yet know of the feminist ideas to which her daughter, Rachel, would later introduce her, but the idea that she had to defer appears on many pages of the text as a feeling, sometimes as a regret.

I remember my mother once saying, "Jim is the professor, but Janet is smarter than he is." They were both terribly smart and I never saw the need to compare them on that score, but I also suspect my mom was right. You wouldn't know it if all you had was a copy of their résumés. In the memoir, it is clear that strong female friendships helped women of Robertson's generation beat back the ennui that sexism invited.

They moved to Arkansas after graduation, where Jim was stationed in the Army during the Korean War, then back to Cambridge, Massachusetts, and finally to the town in Connecticut where I met them.

Robertson details the difficulties in her marriage, the fact that she never thought of herself as a good mother, and other things that were entirely opaque to me when I knew the family. I idolized their son, Jonathan, who was the only person in our high school who was both super smart and super cool, and it broke my heart to learn of his first, failed marriage and the pain it caused.

Reading this memoir, I was reminded of the opening line of Anna Karenina: "All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." Growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, many of us assumed ours was the only unhappy family. They weren't, and Robertson's willingness to share the struggles as well as the joys of her life make for a compelling and a consoling read.

I remember my mother once saying, 'Jim is the professor, but Janet is smarter than he is.'

Robertson wrote a novel inspired by the circumstances of her grandmother's life, and then she and Jim wrote a book about the family that had lived for several generations in the house they bought in Connecticut. That book, All Our Yesterdays: A Century of Family Life in a Small American Town, was different from the current one, based on collected letters and family documents. But both are representative of the kind of social history that we now take for granted but that scarcely existed before the last third of the 20th century. Most previous histories dealt only with kings and popes and generals and armies, not with the lives of more typical citizens.

In the current memoir, of course, Robertson's memory fills in many gaps that were not fillable when dealing only with the written records of people long dead. One item did not make the list of significant happenings in our little town, and I was surprised by that. In the early 1970s, our town had been riven by the decision to build a small regional high school. It was an ugly fight.

The Robertsons, along with my uncle Bob and a few other leading citizens in the town, decided to form a community players' troupe to help bind up the wounds. Mrs. Robertson and my mother worked behind the scenes on props and programs and costumes, while Jim and my uncle Bob frequently played the lead roles.

Finally, one year, the troupe chose to stage "Arsenic and Old Lace," and Mrs. Robertson and my mother were cast as Abby and Martha Brewster, the charming old ladies who, in their charity, poison lonely old men and have their nephew bury them in the basement. I admit my bias, but I thought they were splendid.

It is impossible for me to assess how others who did not know Janet Robertson as I did will enjoy this book. But I suspect it will resonate with many people of her generation, and their children. Her generation largely created the cultural world my generation inherited, and we are the better for it. At least I know I am a much better person for having spent those years at Mrs. Robertson's kitchen table, learning Latin — and so much else.