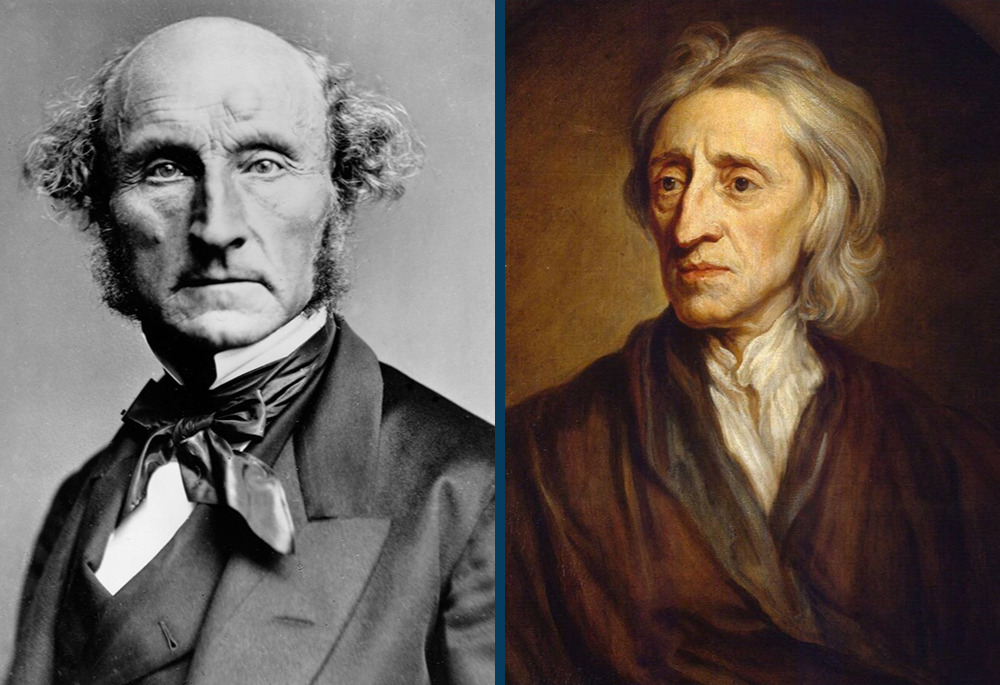

John Stuart Mill, circa 1870 (left); "Portrait of John Locke," a 1697 painting by Sir Godfrey Kneller (Wikimedia Commons/Hulton Archive/London Stereoscopic Company; Collection of Sir Robert Walpole, Houghton Hall, 1779)

It isn't often that you pick up a book and, within the first few pages, realize this is a book that will necessarily find itself on to the syllabi of almost every course in political philosophy. Even less rare is it when such a realization makes you happy. Jason Blakely's Lost in Ideology: Interpreting Modern Political Life is such a book. It is accessible and rich, detailed and comprehensive, well argued and well written. Most importantly, it helps us better make sense of this crazy political world in which we live.

Blakely, who teaches at Pepperdine University, starts with the most common usage of the word ideology: It is "politics in excess — distorted, immoderate, and delusional." That is why ideology is what the other guy believes, never oneself.

In this book, Blakely offers a different understanding of what ideology is and isn't. "We are meaning-making animals and ideologies are stories about the significance or meaning of social and political life," he writes.

If ideologies are a form of meaning-making, then they are not so different from other forms of cultural production — theatre, literature, sports, cuisine and music — that need to be understood through careful interpretation. Everyone knows that comprehending a rich story (say, one told by Homer or Shakespeare) requires a careful and patient art of interpretation. Yet comparatively few people are willing to lavish this kind of interpretative attention and generosity on ideology. … The more conversant one becomes in multiple ideologies, the less prone one is to treat a favoured politics as natural or obvious.

He proceeds to provide precisely that careful, generous interpretation of various ideologies.

Before turning to this examination of particular ideologies, Blakely rightly warns against some facile temptations that seek to escape interpretation by presenting themselves as authoritative per se. He writes of those who "attempt to inoculate themselves against ideology by proclaiming they believe in nothing more than science." In Catholic circles, you find this phenomenon especially among some environmental activists who appeal to "science-based" ideas as if that ended debate. Blakely acknowledges that "empirical facts and logic do exert some critical force over ideology" nonetheless, "ideologies are visions of a good society that always go beyond the merely factual and logical to pose basic questions of meaning and significance." That is why "they require a broader conception of reason."

Book cover for Lost in Ideology: Interpreting Modern Political Life

The first chapter looks at the varieties of classical liberalism and the influence they have exerted on American political ideology. "Liberalism is a map whose recurring landmarks include: the establishment of individual rights, the formation of government based on a contract, equality before the law, the protection of private property, and an affirmation of religious and ethical tolerance," Blakeley writes. For many theorists, these ideas were, as the declaration called them, "self-evident," or as Thomas Paine said, "nothing more than simple facts, plain arguments, and common sense."

John Locke and others discerned what we know as liberalism in the "state of nature" in pre-colonial America, at least in the North, away from "the conquering swords, and spreading domination of the two great empires of Peru and Mexico." Locke exulted that "in many parts of America there was no Government at all," which was not really true. Besides, why would "nature" and "natural rights" be the rule only in northern climes if they were truly natural and self-evident? Blakely observes that "the true anthropological situation is nearly the exact opposite of Locke's state of nature."

He goes further. The issue is not only what Locke chooses to naturalize, but what he doesn't. "Most readers of the Second Treatise do not meditate enough on the astonishing list of features of human life rendered unnatural simply by not appearing in the Lockean state of nature," Blakely notes. "These include but are not exhausted by: community, revealed religion, the arts, kin networks, friendship, prolonged dialogue, customs, rituals, sports, group play, and on, and on. Of course, many of these very same items are vulnerable to erosion — albeit never fully disappearing — in highly individualistic versions of liberal society." I confess when I read the Second Treatise as an undergraduate, none of this occurred to me.

Locke's essential mistake is one that runs through this book's catalog of ideological progenitors: He takes his own ideas as primordial and given, jumping from insight to ontology with far too much swiftness. "He unwittingly helped invent and promulgate the very thing he believed himself to be simply uncovering empirically," Blakely writes, adding, "part of the very force of Lockean liberalism is that it naturalizes its own politics and therefore covers over its own original creative, even poetic, act."

Blakely's generous reading of both the strengths and weaknesses of liberalism, and of the other ideologies he surveys, extends beyond his assessment of the flawed geniuses that inspired them. For example, he notes:

Again, there is a cultural force to the Lockean map: not meddling in a neighbour's own answer to basic existential questions is a sign of respect for their freedom and independence. Although it might sometimes fall into indifferentism or vulgar relativism, it can also encompass a high standard of the affirmation of human dignity. … Lockean-inspired liberalism is anti-paternalistic and promises a kind of universal adulthood based on the rational and independent exercise of one's own faculties.

These obvious strengths must be balanced against the weakness of the Lockean map. "The primordial myth of a contract gives Lockeans their peculiar cultural perception that all relations are chosen and consensual," Blakely writes. It is a more damning observation than most liberals want to admit and has, at times, made liberals blind to the sufferings of others. Further problems emerge: "If those committed to liberal politics attempt to impose an education inculcating liberal ways of thinking, civility, and tolerant speech, then this appears to violate the sovereign self-ownership of individual rights." These cultural challenges were not addressed by Locke or other early liberal theorists because "they expected a liberalism of interests and sentiments to be innate to the human condition." As we are witnessing in our own time, this cultural blindness is one reason why liberals always seem surprised when the institutions they took such care to erect as protection for the liberal regime prove flimsier than thought.

Advertisement

Blakely goes on to examine the utilitarian turn in liberal thought begun by Jeremy Bentham and furthered by John Stuart Mill. Along the way, Blakely makes some keen observations. "Genius, according to Mill, by definition broke out of conforming patterns of belief and practice. To put it somewhat playfully: the genius of liberalism was its ability to guard the freedom that made for geniuses. … Of course, Mill conceded that many nonconformists were simply cranks and kooks. But he believed society had no way of eliminating all frauds without also snuffing out all geniuses." Such an observation is not merely interesting. Blake builds on it to make an important conclusion about the historical trajectory of liberalism's ideology:

For Mill, all of society benefitted from those willing to stand out and risk being perceived as odd in order to follow their own conscience. This marks a dramatic ideological evolution of classical liberalism to not only absorb utilitarian principles but also romanticism's vision of genius as authentic and nonconforming.

It is rewarding to find such incisive and generous accounts of the ideas of others, and even more when those accounts lead to large cultural conclusions that strike the reader as eminently sound. Blakely's thinking is careful. He doesn't rush out on a limb, but tests it and describes it and learns a great deal about the limb before going out upon it to look back at the trunk from a different angle. There is, too, this essential insight that runs from the first to the last page, that ideology is a cultural product that requires the kind of humanistic attentiveness we afford literature and music and other cultural products. This insight about culture is not only important in its own right, it also keeps the discussion from becoming too abstract and abstruse.

We'll wrap up this review on Monday.