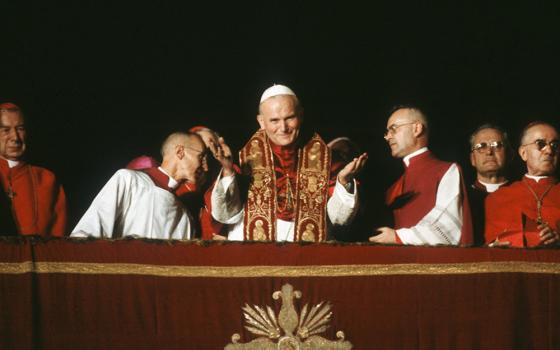

Pope Paul VI is carried in procession on the sedia gestatoria, a ceremonial throne, in this undated photo. Pope Paul, who served as pope from 1963-1978, is most remembered for his 1968 encyclical, Humanae Vitae, which affirmed the church's teaching against artificial contraception. (CNS/Catholic Press Photo/Giancarlo Giuliani)

Editor's note: To celebrate our 60th anniversary, we are republishing articles from our archives. Find more articles here.

It was bombshell news in the Catholic Church and it was on the front page.

In April 1967, when the National Catholic Reporter published the secret recommendations of the Papal Commission on Birth Control submitted to Pope Paul VI, the story ran above the fold on Page 1 — of The New York Times.

With a dateline of KANSAS CITY, Mo., the Times credited NCR, "a liberal, independent weekly published by laymen," for revealing that the majority of the papal commission favored approval of "decent and human means" of contraception.

"MAJORITY REPORT SEEKS PAPAL SHIFT ON CONTRACEPTION," blared the grey lady.

"Advisers to Pontiff Are Split — Both Findings Printed in U.S. Catholic Paper

"NO COMMENT BY VATICAN

"Liberals on Panel Hold View That Marriage Requires Right to Plan Family"

The Times article quoted Robert Hoyt, the storied founding editor of NCR, saying the texts had been obtained from "a member of the commission, whom he would not identify." NCR had a secret source, its own Deep Throat, before anyone ever learned of The Washington Post's nickname for the famous Watergate leaker.

Coming just three years after NCR was founded, these reports, published in full, were the Vatican equivalent of the Pentagon Papers — and before anyone had ever heard of the Pentagon Papers.

The story was also a watershed moment for NCR, emblematic of how NCR revolutionized journalistic coverage of the Catholic Church and how it was understood in the United States.

Publication of the secret findings was seen as scandalous. It was among the reasons that Bishop Charles Helmsing of Kansas City-St. Joseph, Missouri, condemned NCR and demanded that the paper remove the word "Catholic" from its name. The taint was such that seminarians were told reading NCR was strictly prohibited, a priest now in a parish in California recently told NCR.

The leaked internal texts of the commission, initially formed by Pope John XXIII and then expanded by Paul VI, exposed a deep philosophical and theological rift over the use of contraception.

The majority report — signed by prelates, theologians and expert-consultors — argued that contraception was justified on the need for fulfillment in marriage, which it said included sexual fulfillment and the right to plan the number of children the family can care for and prepare "for a truly human life."

The minority held firm with past church teachings that birth control outside of natural family planning, or the rhythm method, was "intrinsically evil."

The year following the publication of the paper, Paul VI rejected the majority report and instead sided with the minority of his commission.

The 1968 issuing of Humanae Vitae marked one of the most controversial chapters in recent church history. The encyclical from Paul VI, subtitled "On the regulation of birth," affirmed the church's total ban on contraception with appeals to natural law and magisterial infallibility.

Humanae Vitae was met with varied reactions, including open dissent from episcopal conferences and theologians.

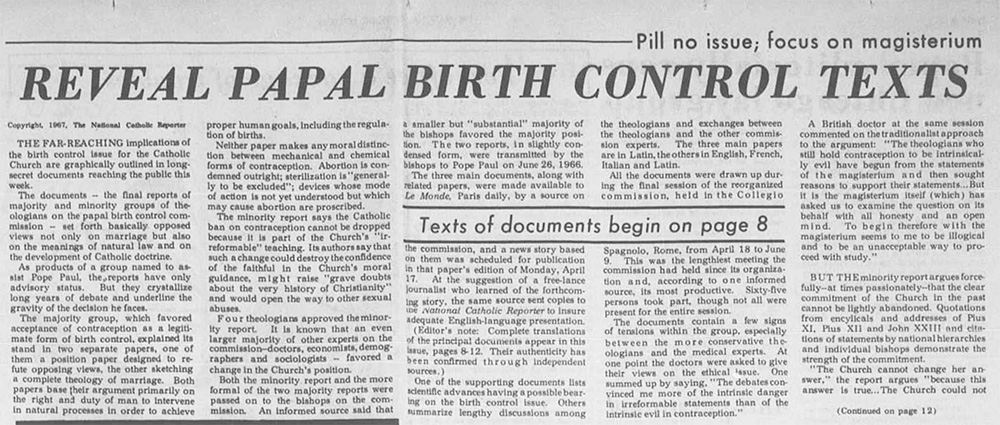

The article on the papal birth control texts appeared on Page 1 of the April 19, 1967, issue of the National Catholic Reporter. (NCR screenshot)

The secret documents also were leaked to the French daily Le Monde. Written mainly in Latin, with other sections in French, Italian and English, NCR broke the news to the Anglosphere with a meticulously reported story, as well as the publication of the three major documents.

The article, republished here, affords today's readers an opportunity to examine the tensions of the time, which modern Catholics have inherited. The conservative minority relied on natural law and warnings that high-profile moral reform would undermine the church's moral authority. The liberal majority went so far as to sketch a renewed Catholic theology of marriage, reminding the pope that sacred Scripture augments "increase and multiply" with "they shall be two in one flesh."

As NCR celebrates its 60th year of independent reporting on the Catholic Church, the NCR family is inspired by the treasures reprinted here. And NCR will continue its legacy of fearlessly publishing difficult, urgent and revelatory stories.

REVEAL PAPAL BIRTH CONTROL TEXTS

Pill no issue; focus on magisterium

Pg. 1, April 19, 1967

THE FAR-REACHING implications of the birth control issue for the Catholic Church are graphically outlined in long secret documents reaching the public this week.

The documents — the final reports of majority and minority groups of theologians on the papal birth control commission — set forth basically opposed views not only on marriage but also on the meanings of natural law and on the development of Catholic doctrine.

As products of a group named to assist Pope Paul, the reports have only advisory status. But they crystallize long years of debate and underline the gravity of the decision he faces.

The majority group, which favored acceptance of contraception as a legitimate form of birth control, explained its stand in two separate papers, one of them a position paper designed to refute opposing views, the other sketching a complete theology of marriage.

Both papers base their argument primarily on the right and duty of man to intervene in natural processes in order to achieve proper human goals, including the regulation of births.

Neither paper makes any moral distinction between mechanical and chemical forms of contraception. Abortion is condemned outright; sterilization is "generally to be excluded"; devices whose mode of action is not yet understood but which may cause abortion are proscribed.

The minority report says the Catholic ban on contraception cannot be dropped because it is part of the Church's "irreformable" teaching. Its authors say that such a change could destroy the confidence of the faithful in the Church's moral guidance, might raise "grave doubts about the very history of Christianity" and would open the way to other sexual abuses.

Four theologians approved the minority report. It is known that an even larger majority of other experts on the commission — doctors, economists, demographers and sociologists — favored a change in the Church's position.

Both the minority report and the more formal of the two majority reports were passed on to the bishops on the commission. An informed source said that a smaller but "substantial" majority of the bishops favored the majority position. The two reports, in slightly condensed form, were transmitted by the bishops to Pope Paul on June 26, 1966.

The three main documents, along with related papers, were made available to Le Monde, Paris daily, by a source on the commission, and a news story based on them was scheduled for publication in that paper's edition of Monday, April 17. At the suggestion of a free-lance journalist who learned of the forthcoming story, the same source sent copies to the National Catholic Reporter to ensure adequate English-language presentation.

(Complete translations of the principal documents appear in this issue, pages 8-12. Their authenticity has been confirmed through independent sources.)

One of the supporting documents lists scientific advances having a possible bearing on the birth control issue. Others summarize lengthy discussions among the theologians and exchanges between the theologians and the other commission experts. The three main papers are in Latin, the others in English, French, Italian and Latin.

All the documents were drawn up during the final session of the reorganized commission, held in the Collegio Spagnolo, Rome, from April 18 to June 9. This was the lengthiest meeting the commission had held since its organization and, according to one informed source, its most productive. Sixty-five persons took part, though not all were present for the entire session.

The documents contain a few signs of tensions within the group, especially between the more conservative theologians and the medical experts. At one point the doctors were asked to give their views on the ethical issue. One summed up by saying, "The debates convinced me more of the intrinsic danger in irreformable statements than of the intrinsic evil in contraception."

Advertisement

A British doctor at the same session commented on the traditionalist approach to the argument: "The theologians who still hold contraception to be intrinsically evil have begun from the statements of the magisterium and then sought reasons to support their statements ... But it is the magisterium itself (which) has asked us to examine the question on its behalf with all honesty and an open mind. To begin therefore with the magisterium seems to me to be illogical and to be an unacceptable way to proceed with study."

But the minority report argues forcefully — at times passionately — that the clear commitment of the Church in the past cannot be lightly abandoned. Quotations from encyclicals and addresses of Pius XI, Pius XII and John XXIII and citations of statements by national hierarchies and individual bishops demonstrate the strength of the commitment.

"The Church cannot change her answer," the report argues "because this answer is true ... The Church could not have erred through so many centuries, even through one century, by imposing under serious obligation very grave burdens in the name of Jesus Christ, if Jesus Christ did not actually impose these burdens."

Elsewhere the point is reinforced by reference to Protestant teachings:

"If contraception were declared not intrinsically evil, in honesty it would have to be acknowledged that the Holy Spirit in 1930, in 1951 and 1958, assisted Protestant Churches, and that for half a century Pius Xl, Pius XII and a great part of the Catholic hierarchy did not protect against a very serious error, one most pernicious to souls."

"Therefore," the document adds, "one must very cautiously inquire whether the change which is proposed would not bring along with it a definitive depreciation of the teaching and the moral direction of the hierarchy of the Church and whether several very grave doubts would not be opened up about the very history of Christianity."

On the philosophical level, the report acknowledges that arguments from reason for the ban on contraception are not fully satisfying. "If we could bring forward arguments which are clear and cogent based on reason alone, it would not be necessary for our commission to exist, nor would the present state of affairs exist in the Church."

But the authors argue that generative acts and processes have always been held to be inviolable precisely because they are generative; Just as human life is removed from the control of man, so also are the sources of life. It was for this reason that the Fathers frequently compared contraception with homicide.

One philosophic argument sketched by the conservatives recalled the views of Dr. Germain Grisez, Georgetown university professor, who argues that since procreation is one of the fundamental human goods, any voluntary action against it is intrinsically evil.

The statement gives greater emphasis, however, to the evil effects the authors say would be brought about by change and by acceptance of the arguments for change. They contend these arguments make the idea of natural law uncertain and changeable and withdraw it from the clarifying interpretation of the magisterium.

Other arguments favoring contraception, they say, could be used to justify extramarital sex, perverse sexual acts in marriage, masturbation and direct sterilization. The concept of natural law undergirding the case for change reflects an "earthly, cultural naturalism" and a "utilitarian, exceedingly humanistic altruism," say the conservatives, and they suggest that those who support such ideas may be unduly influenced by their own time and culture, "so that they bring to the problem only a partial transitory and vitiated vision."

The two statements drawn up by the liberal majority present a strong contrast.

The first, entitled "The Morality of Birth Control," argues the case for contraception and rebuts the conservative counterarguments. The second, "Responsible Parenthood," may have been intended to provide the basis for a papal statement settling the birth control issue but going beyond it to attempt an integrated contemporary theory of Christian marriage.

The position paper on birth control begins by denying that Pius XI's formal condemnation of contraception in Casti Connubii is infallible Catholic teaching. It says today's scholars interpret the story of Onan, cited by the Pope, differently from the way it is used in the encyclical, that the argument from reason given in the encyclical is "vague and imprecise," and that the tradition to which Pope Pius refers to is not of apostolic origin or an expression universal faith.

The basic fault of the tradition, according to the liberals, rests in its conception of natural law, which makes nature the voice of God and fails to understand man's call to take command of nature and shape it to good human purposes.

"Churchmen," the document acknowledges, "have been slower than the rest of the world in clearly seeing this as man's vocation." Later, responding to the conservative arguments for the inviolability of the "sources of life," the majority theologians say:

"But unconditional respect for nature as it is in itself ... pertains to a vision of man which sees something mysterious and sacred in nature and because of this fears that any human intervention tends to destroy rather than perfect this very nature." The same attitude has slowed medical and scientific progress in the past, the report says.

The "sources of life," it later adds, are not the sex organs, but married persons who act voluntarily and responsibly in conjugal acts. To contemporary man, it seems more in keeping with rational nature to use the skills of mankind to intervene in natural processes to achieve the ends of marriage than to leave conception wholly to chance.

Other causes for fresh thought on the issue, the document says, are "the social change in marriage, in the family, in the position of woman; the diminution of infant mortality; advances in physiological, biological, psychological and sexological knowledge; a changed estimation of the meaning of sexuality and of conjugal relations," all of which have helped bring "a better, more profound and more correct perspective on married life and intercourse."

The liberals meet head-on the conservative argument — that the Holy Spirit could not permit the persistence of error in the Church:

"The criteria for discerning what the Spirit could or could not permit in the Church can scarcely be determined a priori. In point of fact we know that there have been errors in the teaching of the magisterium and of tradition." The report cites the once-prevalent view of theologians that marital intercourse was wrong unless it was intended for procreation or "at least ... to offer an outlet for the other partner." This view is now abandoned by all, the report says.

Arguing that in practice the "authentic non-infallible magisterium" has in recent times been treated as if it were infallible, the authors of the document say that a change on the contraception issue would bring "a more mature comprehension of the whole doctrine of the Church." It is sound theology, they say, to reconsider any doctrine when there are good reasons for doubt about its force.

The document denies that change on the birth control issue would be a surrender to "subjectivism or laxism." Man's right to control nature does not permit complete exclusion of fertility from marriage, but it does permit the use of rhythm or other "decent" means — to be weighed according to "objective criteria" — in order to render particular acts infertile for good reasons.

The document echoes language familiar in Planned Parenthood campaigns in speaking of an "obligation of conscience" for not having a child in some circumstances and of the right of children to "community of life and unity" and to proper education.

Acts of contraceptive intercourse can be justified, the theologians contend, because "sexuality is not ordered only to procreation ... Sacred Scripture says not only 'increase and multiply,' but 'they shall be two in one flesh' ... In some cases intercourse can be required as a manifestation of self-giving love, directed to the good of the other person or of the community ... This is neither egocentricity nor hedonism but a legitimate communication of persons through gestures proper to beings composed of body and soul with sexual powers."

The document contains almost no discussion of specific forms of contraception. A source on the commission was asked whether serious consideration was given to approval of the pill but not to mechanical means of contraception. Avoiding direct reply, he said, "The commission's interest was mostly centered on the nature of marriage."

He was asked also whether the commission held any opinion about which methods of contraception were most acceptable, apart from a couple's individual circumstances. He said it was not the commission's intention "to draw up specific rules in the old casuistic style."

But the document insists that couples must make a "moral decision" concerning methods, taking the "objective criteria" into account. Among the criteria:

— The method should be "conformed to the dignity of love and to respect for the dignity of the partner."

— It should be efficacious, "fitting and connatural," and accomplished with lesser inconveniences to the subject."

Rhythm, the document said, is deficient because for many couples it is not effective. It points out that "only 60 percent of women have a regular (menstrual) cycle."

The document denies that legitimizing contraception would foster an indulgent attitude toward abortion, fornication, adultery, sexual perversions and masturbation. Abortion, it says, deals with human life already in existence and is wholly different from contraception. Other sexual sins cited by conservatives are banned at least as strictly by the liberal view the report maintains.

Of the three documents, the second statement drawn up by the majority is the least easily summarized, the one containing the least immediate "hard news" and possibly the one with the greatest long-term significance.

On the specific issue of contraception the paper "On Responsible Parenthood" repeats many of the key arguments of the working paper. But the treatment of contraception comes late in the document and the authors attempt to integrate it into a developed view of marriage which preserves basic values defended by the Church in earlier times.

Opening passages of the report contain passages reminiscent of the writings of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, French Jesuit scientist-philosopher who spent much of his life under a cloud of suspicion for his bold attempt to join Christianity with an optimistic, forward-looking view of science and other contemporary developments.

In the report man is again presented as cooperator with God in directing nature to human ends and in fulfilling his own nature. The Church's new opening to dialogue is praised and the work of the commission is praised as an instance of such dialogue.

The final report makes a greater effort than the working paper to preserve continuity between the new position it proposes and the Church's earlier teaching. It points to the new stress in Casti Connubii on the "mutual inward moulding of husband and wife" as a "chief reason and purpose of matrimony."

But the document also borrows freely from terminology and arguments developed by Protestant thinkers and similar sources. It speaks of "responsible — that is generous and prudent — parenthood," and acknowledges that in considering the size of their family a couple should take into account the needs of the whole society as well as of their existing children.

It defines a "contraceptive mentality" — a term often used by Catholic opponents of contraception — as one that is "egoistically and irrationally opposed to fruitfulness." But the mere acceptance of contraception, it is clear, does not in the view of the authors constitute such a mentality, any more than would the use of rhythm!

"The true opposition is not to be sought between some material conformity to the physiological processes of nature and some artificial intervention. For it is natural to man to use his skill in order to put under human control what is given by physical nature. The opposition is really to be sought between one way of acting which is contraceptive and opposed to a prudent and generous fruitfulness, and another way which is in an ordered relationship to responsible fruitfulness and which has a concern for education and all the essential, human and Christian values."

After reaffirming the condemnation of abortion, the document adds: "Sterilization, since it is a drastic and irreversible intervention in a matter of great importance, is generally to be excluded as a means of responsibly avoiding conceptions."

In a section on "Pastoral Necessities," the document calls for an educational renewal to acquaint couples with the duty of responsible parenthood: "The more urgent the appeal is made to observe mutual love and charity in every expression of married life, the more urgent is the necessity of forming consciences, of educating spouses to a sense of responsibility and of awakening a right sense of values."

The document calls for the establishment of a pontifical institute to conduct research on problems of married life, and suggests that the commission's own work could be made public to launch further reflection. It suggests also the formation of regional bodies under the direction of episcopal conferences.

On population problems, the statement is reserved. It gives only slight encouragement to government intervention in the form of "political demography," and warns against regarding increases in population as "something evil or calamitous for the human race."