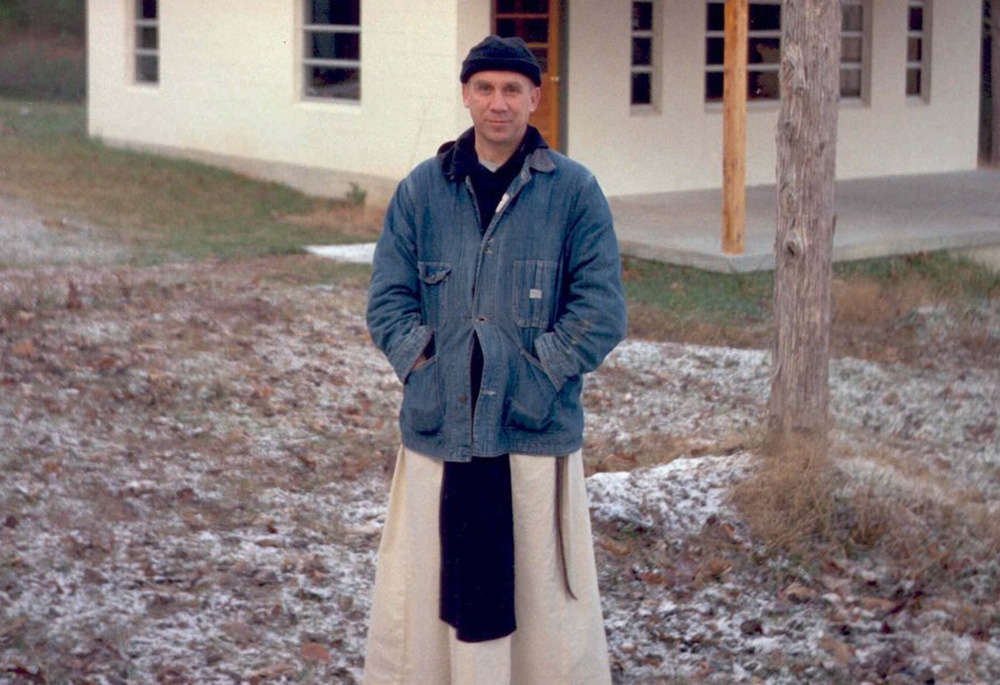

Trappist Father Thomas Merton, one of the most influential Catholic authors of the 20th century, is pictured in an undated photo. (CNS/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University)

Given the recent atrocities in Israel and Gaza, the terrorist actions of Hamas and the state of Israel's initial retaliation and plans for a massive ground attack, war and escalating violence has been on the minds and hearts of many around the world. This latest war is added to the nearly two-year-long war in Ukraine following Russia's invasion of that sovereign nation in February 2022 and the dozens of other conflicts across the globe, including ongoing civil wars in Yemen, Libya, Myanmar, Syria and the Central African Republic, among other forms of violence and instability.

In his 2020 encyclical letter Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis acknowledged that "conditions that favor the outbreak of wars are once again increasing" and described the breakout of state and terrorist violence across the planet as reflecting a new and disturbing reality: "In today's world, there are no longer just isolated outbreaks of war in one country or another; instead, we are experiencing a 'world war fought piecemeal,' since the destinies of countries are so closely interconnected on the global scene."

It is easy to be overcome by the magnitude of the violence and the acute hopelessness that surfaces when the scale of destruction, violence and injustice comes to the surface. In Fratelli Tutti, the pope named this sense of apathy and willful ignorance that arises in the face of such global violence. "In today's world, the sense of belonging to a single human family is fading, and the dream of working together for justice and peace seems an outdated utopia. What reigns instead is a cool, comfortable and globalized indifference, born of deep disillusionment concealed behind a deceptive illusion: thinking that we are all-powerful, while failing to realize that we are all in the same boat."

So, to what or whom can we turn to think about what is happening in Israel and Gaza, Ukraine and central Africa, Southeast Asia and elsewhere?

When I am overwhelmed by the magnitude of global violence, I find myself returning to an essay by the Trappist monk and author Thomas Merton. "The Root of War Is Fear" appears in Merton's 1961 book New Seeds of Contemplation and was also published in a slightly expanded form in The Catholic Worker in October of the same year.

While Merton was well known for his criticism of war and violence, especially in the 1960s during the Vietnam War, the Cold War and the fight for civil rights in the United States — often writing about the systemic and global dimensions of conflict — the essay, "The Root of War Is Fear" brilliantly (and unsettlingly) turns the critical focus inward and invites all of us to a deep examination of conscience.

Merton writes at the outset of the essay:

At the root of all war is fear: not so much the fear men have of one another as the fear they have of everything. It is not merely that they do not trust one another; they do not even trust themselves. … It is not only our hatred of others that is dangerous but also and above all our hatred of ourselves: particularly that hatred of ourselves which is too deep and too powerful to be consciously faced. For it is this which makes us see our own evil in others and unable to see it in ourselves.

Some may find Merton's opening challenge to moral self-examination off-putting when few of us are directly responsible for the sort of violence and bloodshed we see around the world today. But Merton wants us to look beneath the superficial descriptions and breaking news, to ask ourselves the tough question: Why does this kind of violence exist and what role might we have in it?

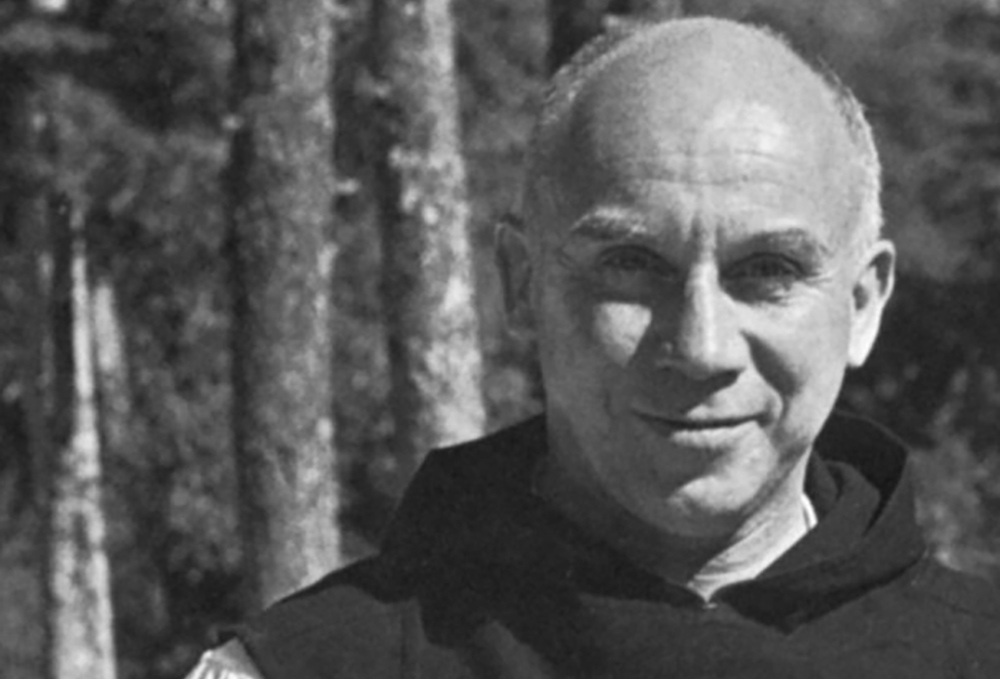

Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton in 1968 (CNS/Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University)

Merton is careful across his writings not to offer false equivalencies — he does not believe that all people are equally culpable for the violence in this world. But he does believe that all people are implicated in some capacity on account of our interconnectedness and ethical obligations we have to one another. In this way, I believe Merton would agree with his friend and correspondent, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, who wrote in his classic 1962 book The Prophets, "Above all, the prophets remind us of the moral state of a people: Few are guilty, but all are responsible."

If we take this to be a fundamental truth of the human condition, then we are all in need of further introspection. The choices that lead to violence begin with a similar, if unequal, origin within the heart of people in positions to actualize destruction on various scales. For some, it is the verbal, psychological, emotional, physical or sexual violence perpetrated against an individual or small group. For others, like state actors and terrorist organizations, it is exercised in unthinkably wide-ranging ways.

Merton writes: "We drive ourselves mad with our preoccupation and in the end there is no outlet left but violence. We have to destroy something or someone. By that time we have created for ourselves a suitable enemy, a scapegoat in whom we have invested all the evil in the world. He is the cause of every wrong. He is the fomenter of all conflict. If he can only be destroyed, conflict will cease, evil will be done with, there will be no more war."

Advertisement

Many times, teaching Merton's writings and thoughts on nonviolence and peacemaking, I have found students resist the claim Merton makes that we are all responsible in some way for the perpetuation of manifold forms of violence in this world. We are desperate, as he notes, to identify the "other" outside ourselves, some kind of monster who is unlike us and therefore the "real" cause of violence, so that we can reassure ourselves of our own false innocence and absolve ourselves of the little and big forms of violence in our own lives.

It is this way of thinking, certainly shaped by the effects of original sin experienced by all, that precludes us from seeking real peace, which is peace that the world cannot give, as Jesus famously taught us (John 14:27). As Merton says, "The peace the world pretends to desire is really no peace at all."

But at a time when solidarity and prayer are needed, but are themselves not enough, I find Merton's exhortation to the Christian community instructive. As an individual, I may not be able to effect substantive change in the Holy Land or Eastern Europe or Central Africa, but I can work on modulating how I personally contribute to violence in this world in my own life and thinking.

As an individual, I may not be able to effect substantive change in the Holy Land or Eastern Europe or Central Africa, but I can work on modulating how I personally contribute to violence in this world in my own life and thinking.

I have found that the closing paragraph of Merton's essay serves as a good reminder of the personal spiritual work I need to do at a time like this to prepare me for greater clarity of vision and interpretation regarding global violence:

So instead of loving what you think is peace, love other men and love God above all. And instead of hating the people you think are warmakers, hate the appetites and the disorder in your own soul, which are the causes of war. If you love peace, then hate injustice, hate tyranny, hate greed — but hate these things in yourself, not in another.

If we all worked on this, then maybe we could move from the individual to the collective. And then perhaps the human family would be better able to embrace what Pope Francis says in Fratelli Tutti, "We can no longer think of war as a solution, because its risks will probably always be greater than its supposed benefits. In view of this, it is very difficult nowadays to invoke the rational criteria elaborated in earlier centuries to speak of the possibility of a 'just war.' Never again war!"