Massimo Faggioli of Villanova University speaks at an Oct. 13-15 conference at Sacred Heart University, "Vatican II and Catholic Higher Education: Leading Forward," which marked the 60th anniversary of the opening of the Second Vatican Council. (Sacred Heart University/Chris Zajac)

Last week, Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut, marked the 60th anniversary of the opening of the Second Vatican Council by hosting a wonderful conference, "Vatican II and Catholic Higher Education: Leading Forward." The school, which is celebrating its 60th anniversary next year, was a fruit of the council, the first Catholic university under lay leadership in the country.

The event was part of a growing body of evidence that a significant minority of U.S. Catholic theologians are reengaging with Vatican II, and ecclesiology more generally, in important ways.

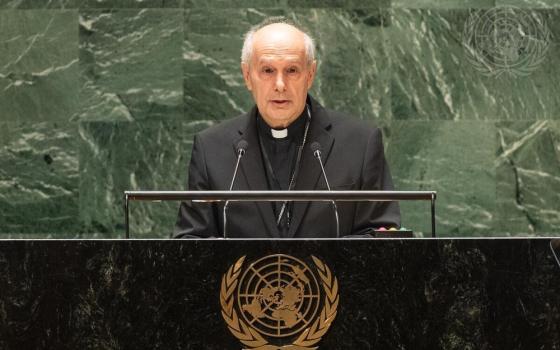

Massimo Faggioli of Villanova University opened the proceedings and set the frame for the entire conference with a historical and theological reflection on the reception of Vatican II in Catholic higher education in the United States. Unsurprisingly, he invited the participants to honest self-criticism of their guild as well as pointing a way forward.

A Vespers service on Oct. 13 during Sacred Heart University's conference "Vatican II and Catholic Higher Education: Leading Forward" (Sacred Heart University/Chris Zajac)

Vatican II "assumed a robust relationship between theology and academia," Faggioli said. "The new literary genre of Vatican II texts, that is, non-legislative but narrative, required a sustained effort of cultural mediation between magisterium, the church and the world that was different from one of the most similar predecessors of Vatican II, the Council of Trent four centuries before."

Alas, in the United States, the relationship took a torpedo when Pope Paul VI issued his encyclical Humanae Vitae in 1968.

"This was the beginning of an age of dissent which took different forms between the laity in the pews, the clergy and academic theology," Faggioli explained. "It was a dissent that, in its wisest forms, tried to distinguish carefully between different levels of authority of church teaching. It was the attempt at a loyal or faithful dissent, not an assault on church teaching or papal authority per se — quite different from the one we have seen in recent years against Pope Francis' pontificate."

'Catholic theology pays the price of a largely still ultramontane church which considers the popes (one pope only, of their choosing) the legal executors of the will of Vatican II.'

—Massimo Faggioli

Still, the documents of Vatican II remained a kind of common ground for theological discussion.

In the 1990s, however, Vatican II began to recede from the consciousness of American theology. A "process of mutual alienation" begins, with "a theological-political neoconservative revision of the effects of the council, in the name of an idealized past, in a defense of that recent pre-Vatican II past that many thought Vatican II had made unusable and against a liberal-American interpretation of the conciliar teaching." This revision became more radical in the current century with direct attacks on Vatican II itself.

On the left, a growing ignorance of the conciliar texts and of the event of the council itself began to dominate.

"It is not an attack against Vatican II, but a silent decoupling, a process of estrangement from the conciliar tradition in favor of the post-conciliar, in the sense not just of the post-confessional but also of the post-tradition or anti-tradition," Faggioli said. "This has causes that were both internal to academia (the precarious position of theology in Catholic colleges and universities; the system of academic recruitment and career) and external (understandable frustration with the perceived failure of the church to deliver on the promises of Vatican II). It is an indirect disqualification of Vatican II which creates a vacuum to be filled by other kinds of theological and academic programs."

Looking at the status of Vatican II today, Faggioli noted, "The Catholic theological project finds itself, in terms of church politics, between the Scylla of the German pope, criticized on the one hand as the theologian who stifled theological debate, and the Charybdis of the Argentine pope, criticized by others as the 'street priest' from the Global South who mortifies intellectual precision."

Faggioli added, "Catholic theology pays the price of a largely still ultramontane church which considers the popes (one pope only, of their choosing) the legal executors of the will of Vatican II."

'We've witnessed the insinuation of the corporate lexicon into higher education, transposing deep questions of mission into grammars of innovation and vague notions of human flourishing.'

—Susan Reynolds

Emory University's Susan Reynolds delivered an excellent paper titled "What, for the University, Is Solidarity?: Catholic Higher Education and the Unfinished Reception of Gaudium et Spes."

Reynolds looked at the challenges facing those who seek to discern what solidarity means in the current Catholic academic world. She first cited the fact that "the modern corporate university is governed by tensions that militate against the possibility of solidarity with the poor. ... It is hard to extoll for students the virtues of what Jesuit Dean Brackley called downward mobility and then send them a tuition bill for $75,000."

In addition to the bill, the influence of corporate life also afflicts ideas, Reynolds said. "We've witnessed the insinuation of the corporate lexicon into higher education, transposing deep questions of mission into grammars of innovation and vague notions of human flourishing." Touché.

The second challenge Reynolds noted was "the tendency toward misplaced perceptions of persecution." She did not spend much time on this theme and it certainly has something to say to ideological partisans of both left and right. I hope she will return to it in the future.

Susan Reynolds, seen in the second row, second from right, attends the conference on Vatican II and Catholic higher education at Sacred Heart University Oct. 13 in Fairfield, Connecticut. (Sacred Heart University/Chris Zajac)

The bulk of Reynolds' talk, however, located the difficulty in applying Catholic ideas about solidarity to university life around "the fragmentary and unfinished reception of Gaudium et Spes in the U.S. ecclesial context."

She noted: "In the U.S. Catholic context, nearly six decades of reflection on the council and its outcomes have produced surprisingly little ecclesiological reflection on what the council's vision of solidarity means for the church ad intra, within itself" (emphasis in original).

There are many historical reasons for this fact but surely, as we mark the 60th anniversary of the council, the process of reception needs to connect some of these dots. It is time to overcome the fact that, "theologically, solidarity assumed a starring role in Catholic social thought and ethics, but it did not enter the postconciliar ecclesiological lexicon with the same force."

One of the best parts of Reynolds' talk was relating the idea of solidarity to that of dialogue, a focus especially useful at this moment of ecclesial synodality. "If solidarity describes the council's relational vision, then dialogue was its praxic corollary," she said.

Advertisement

The adoption of dialogue indicated a deeper change in ecclesial culture, too: "To center dialogue as a metaphor for the church's internal and external relationships, then, was to abandon in a gentle yet definitive way the defensiveness that had long characterized the church's stance toward the world." Gaudium et Spes is part of Vatican II's refutation of the 19th-century defensive crouch toward modernity.

St. Louis University's Grant Kaplan focused his paper on the challenge of handing on the Catholic intellectual tradition, and did so in light of Vatican II's Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, Dei Verbum.

"The larger project of conveying the Catholic intellectual and theological tradition, however, involves a paradox — wanting to hand on something that we come to know is deeper and broader than our grasp of it," he noted.

Handing it on entails "both a remembering and a forgetting, and an attempt to remember what has not just been forgotten, but dis-membered."

Participants in the conference on Vatican II and Catholic higher education receive Communion during Mass at the Chapel of the Holy Spirit at Sacred Heart University Oct. 14. (Sacred Heart University/Tracy Deer-Mirek)

Kaplan briefly examined some of the claims put forward by Yale theologian Willie James Jennings, who argues the Christian theological tradition, at least in its Aristotelian-Thomist iterations, has been thoroughly enmeshed with racism and colonialism. "Unfortunately, the use of tradition in theological education has most often been to promote white self-sufficient masculinity in search of a coherence that would make us safe from seeing our fragment work and conceal what the fragment aims toward: communion," Jennings wrote in After Whiteness.

Kaplan distills the moral stakes: "The critique articulated by Jennings brings into relief a serious question already implied: How can one ethically justify belonging to and retrieving a tradition so fundamentally entangled with something rotten?"

Still, the task of transmitting the tradition remains, and for Catholics it is an ecclesiological question, not merely a cultural one. Kaplan stated:

At this point, it suffices to say that Dei Verbum emphasizes not just what is handed down, but the activity and process of handing down. If the faith is not just a set of facts contained in a collection of texts, but instead a living reality, like a language, then the reality handed down has a way of bridging or collapsing time. ... If my family were the last family, say, to speak Cajun in Louisiana, and I did not pass it down to my children, it would cease to be a living language. In a similar way, the faith is a living faith and the Gospel is a "living Gospel."

From left: Fr. Anthony Ciorra, vice president for mission and Catholic identity at Sacred Heart University; Grant Kaplan of St. Louis University; and NCR columnist Michael Sean Winters are seen at the conference "Vatican II and Catholic Higher Education: Leading Forward" on Oct. 13. (Sacred Heart University/Chris Zajac)

In the case of the Catholic faith, two great councils addressed this issue of handing on tradition, Trent and Vatican II, and between those two events there was "a lively discussion in the theology of tradition, linked with efforts to give an account of dogmatic development and to reckon with the impact of modern historical scholarship on Catholic theology's dogmatic and normative claims." Kaplan focused on the work of German theologian Johann Sebastian von Drey (1777-1853), one of the founders of the Catholic school at Tübingen.

Kaplan's treatment of Drey was fascinating, and what I found most memorable was this quote from Drey addressing the necessity of ecclesial tradition:

If scripture alone is accepted as the means of the tradition of the ideas of religious belief, then the whole of theology is exegesis. But if there exists a living objective reality which is generally recognized as the continuance of the originating event and therefore its most authentic tradition, then the historical witness is found in and through it. The Church is just such a manifestation.

So much for sola scriptura.

Drey was new to me, but Kaplan showed how the 19th-century ideas of the Tübingen school made their way to Vatican II via the ressourcement theologians of the mid-20th century. Finally, at the council, the idea that our Catholic understanding of tradition is of a living tradition, not a mere textual one, is affirmed, and in ways distinct from that of Trent.

Kaplan stated, "Free from the polemical urgencies that prompted the Council of Trent, the authors of Dei Verbum were not primarily motivated to defend the legitimacy of tradition as a source, and could thus emphasize its dynamism: 'The Tradition from the Apostles makes progress in the Church with the help [assistentia] of the Holy Spirit. There is growth in insight into the realities and words handed down [verborum traditorum].' "

This sense of history permitted the church to be open to the modern world in ways not possible previously, and still idiosyncratic for those stuck in a fundamentalist conception of Scripture.

'Does Catholic higher education in 2022 really understand the Vatican II call to solidarity with the poor and afflicted?'

—Patricia McGuire

Trinity University President Patricia McGuire gave the final keynote, in which she focused not so much on how Vatican II affects curriculum, but the "who" and the "how" of Catholic higher education.

"Does Catholic higher education in 2022 really understand the Vatican II call to solidarity with the poor and afflicted, a call that echoes across the years through Vatican documents, including Ex Corde Ecclesiae and more recently in the encyclicals and statements of Pope Francis?" McGuire asked.

She then presented data to indicate the answer is not reassuring. McGuire's paper really requires the reproduction of charts, and so I hope it will be published. Her comments — and her track record at Trinity — paint a path forward that is a challenge to all.

Something is happening in Catholic theological circles, something important, a reengagement with ecclesial institutions and with ecclesial language and ideas. It is dawning on a number of Catholic scholars that there can be no ecclesial reform apart from Vatican II, so they must reacquaint themselves with both the documents and the event, yes, even with the spirit of Vatican II.

Kudos to Sacred Heart University Professor Michelle Loris, President John Petillo and the Lilly Fellows Program for hosting this important event, bringing together scholars from the center-right and the center-left to engage in such a stimulating, self-critical and fecund conversation.

Professor Michelle Loris speaks during Sacred Heart University's conference on Vatican II and Catholic higher education conference Oct. 13. (Sacred Heart University/Chris Zajac)

In addition to the Sacred Heart gathering, the recent conference at Boston College to honor the work of Professor Richard Gaillardetz, and especially Gaillardetz's talk, urged this kind of theological reengagement with the church itself.

So, too, does a new research project from the Migrants and Refugees Section at the Vatican's Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, "Doing Theology from the Existential Peripheries." The project launched earlier this month and includes the work of theologians around the world.

Future historians can better determine why academic theology in the U.S. became so estranged from conciliar thought and from ecclesial decision-makers. The important thing now is to seize the momentum and build on it. Carpe diem.

There can be no ecclesial reform outside of Vatican II, period. Not all Catholic theologians need to be ecclesiologists, but Catholic theologians who do not care about ecclesiology at all are not really doing Catholic theology. They are doing something else.