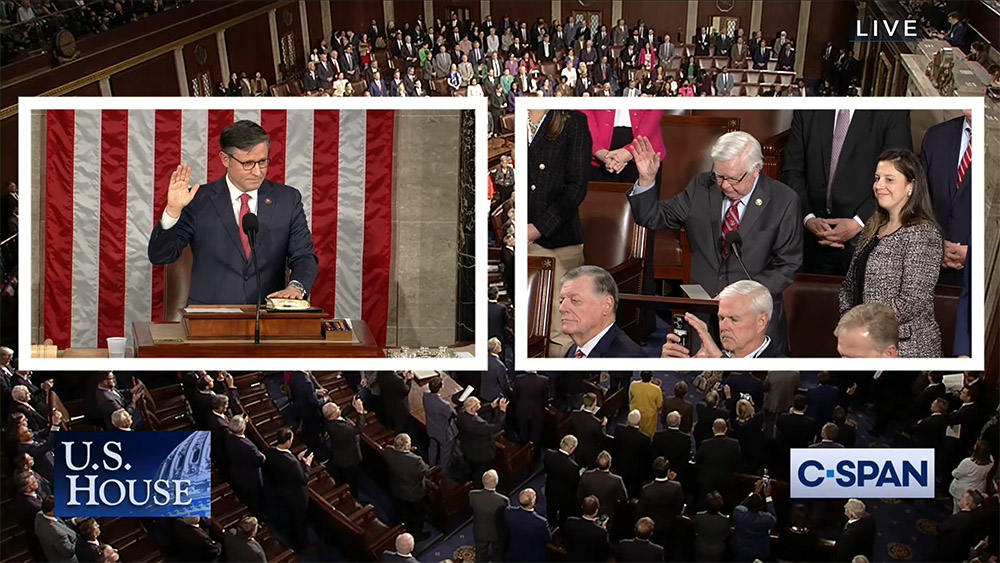

Speaker of the House Mike Johnson takes the oath of office on Oct. 25 administered by Dean of the House Hal Rogers. (Wikimedia Commons/C-SPAN)

In his first public interview after being elected speaker of the House, Rep. Mike Johnson, R-Louisiana, told Fox News' Sean Hannity: "I am a Bible-believing Christian. Someone asked me today in the media, they said, 'People are curious, what does Mike Johnson think about any issue under the sun?' I said, 'Well, go pick up a Bible off your shelf and read it.' That's my worldview."

It is never our place, as a Catholic publication, to judge the internal doctrinal or disciplinary tenets of another religion. However, in the case of the new speaker of the House, the principal issue is how he brings his religion into politics.

Besides, Johnson's is not actually a "different religion." The Bible forms the worldview of all Christians, but it does so differently for some than others.

First, we note that Johnson did not say the Bible forms his worldview. He said it is his worldview. The lack of any sense of mediation has stalked Protestantism since Martin Luther nailed his theses to the chapel door in Wittenberg.

Johnson is assuming the meaning of the Bible is uncontested, that his interpretation is the only available one. He is unalert to the subjectivism of his reading of any particular text and is claiming for what may be a personal and even idiosyncratic reading of the text and the full authority of the Scriptures.

Unsurprisingly, this confusion about the relationship between text and reader issues is a series of equally confusing political misunderstandings, not least about the nation's founding.

In 2016, he gave a truly frightening talk in which he seems to blame the teaching of evolution for the birth of moral relativism, which, in turn, he says is the reason there have been school shootings. The connections between those three multifaceted realities — evolution, moral relativism and school shootings — are a bit more complicated than Johnson allows.

Equally troubling is Johnson's comment about the "natural law philosophy" he says the founders espoused. There were a lot of influences on the founders, and natural law theories were part of the equation. But invoking natural law begins a discussion, it doesn't end it, as Johnson seems to think. As with his understanding of the Bible, he ignores the possibility of a variety of understandings in favor of his own.

An Associated Press story about Johnson's involvement with a Christian law school that never got off the ground said that Tony Perkins, president of the Family Research Council, is a "longtime mentor" to the new speaker. It is ridiculous that the Southern Poverty Law Center labels the Family Research Council a "hate group," but the council has always been an outlier, not least because of the way it mixes modern psychology with fundamentalist Christianity.

Perkins went on New Tang Dynasty News, an outlet sponsored by the Falun Gong religious movement, to discuss his friendship with Johnson.

"He is a thoughtful, caring, deep thinker," Perkins said. Later in the interview, Perkins said, "He's not an enigma. ... As Christians engage in the political process who are Bible-believing Christians, it's not difficult to figure out where we're coming from."

Perkins claimed the founders believed that the principles of Scripture gave "guidance to us on how we should live and how we should influence the world around us." Measurements of depth, of course, are relative. And if by "founders" he meant the pilgrims who landed at Plymouth, he is onto something. Usually, however, a reference to the "founders" means the men who attended the Constitutional Convention in 1787. That assembly was led by George Washington, and he was most certainly not a Christian, but a Deist.

My colleague Mark Silk, at Religion News Service, challenged Johnson's religious bona fides from a different angle: a gross misreading of the Hebrew Scripture.

Advertisement

"When it comes to immigration, Johnson has criticized 'the left' for misreading the biblical injunction to welcome the stranger," Silk writes. "What the Bible teaches, he said, is a practice of 'personal charity' that is 'never directed to the government.' Welcoming the stranger is an exhortation to 'individual believers,' while the government's duty is to enforce laws preventing the influx of migrants."

Silk rightly notes that this is exegetical nonsense. Ancient Israel was, strictly speaking, a theocracy, and God's commandments were directed to both the individual and the community. Indeed, distinguishing the individual from the community the way Johnson does is unique to the modern era.

Now, some of Johnson's critics are way, way over the top and just as badly informed and bigoted as they allege he is. At the Daily Beast, David Rothkopf accuses Johnson of being a "Christofascist" which seems extreme.

Rothkopf also misunderstands the founding, writing, "The founders were breaking with an England and Europe that were still in the thrall of the idea that rulers derived their powers from heaven above, 'the divine right of kings.' "

In parts of Europe, that idea was still believed, and in the center of Italy, the pope was still ruling as monarch. But in England — the country that overwhelmingly shaped what became the U.S. — the "divine right of kings" had not survived the Puritan Revolution of the mid-17th century nor the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688.

N.B. to those who invoke the founding for religious purposes, for or against. Some of the people who most supported the First Amendment clause barring an establishment of religion by the new federal government were those defending the establishment of religion at the state level. Until the adoption of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution in 1868, the Bill of Rights did not apply to state governments. Some states, such as Connecticut, Massachusetts and New Hampshire, had established religions into the 19th century. So, historians of the era can cast plagues on both extremes, the Mike Johnsons of the world and those who think the founding was a purely secular event.

A writer at the Daily Beast (or at NCR), however, is not second in line to become president of the United States. We don't set the calendar for the lower chamber of Congress. We can't issue subpoenas. Johnson can.

He, like every American, is entitled to take his inspirations where he wishes. But when he addresses public policy, he needs to come with something better by way of justification than some lousy exegesis of the Bible, and with a bit more nuance about translating moral norms into public policy.