Rep. Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., sits after the 13th round of voting for speaker in the House chamber as the House meets for the fourth day to elect a speaker and convene the 118th Congress Jan. 6 in Washington. (AP photo/Andrew Harnik)

If the world of politics in 2022 was characterized by increasing polarization between the left and the right, the political life of the nation in 2023 will be increasingly marked by antagonisms within the ideological groupings that shape American politics. This was on vivid display during the fight over the speakership last week. Secondly, these intra-party fights will largely frustrate most attempts at legislation in the new year, as the margins in both chambers of Congress are so tiny, leaders in the House and Senate cannot afford to lose any of their members. Finally, three realities over which politicians have little control will affect our political life in ways it is impossible to predict beyond noting that the effects will be significant: the economy, migration and the war in Ukraine.

And religion could, or should, play a role in all of these likely political struggles.

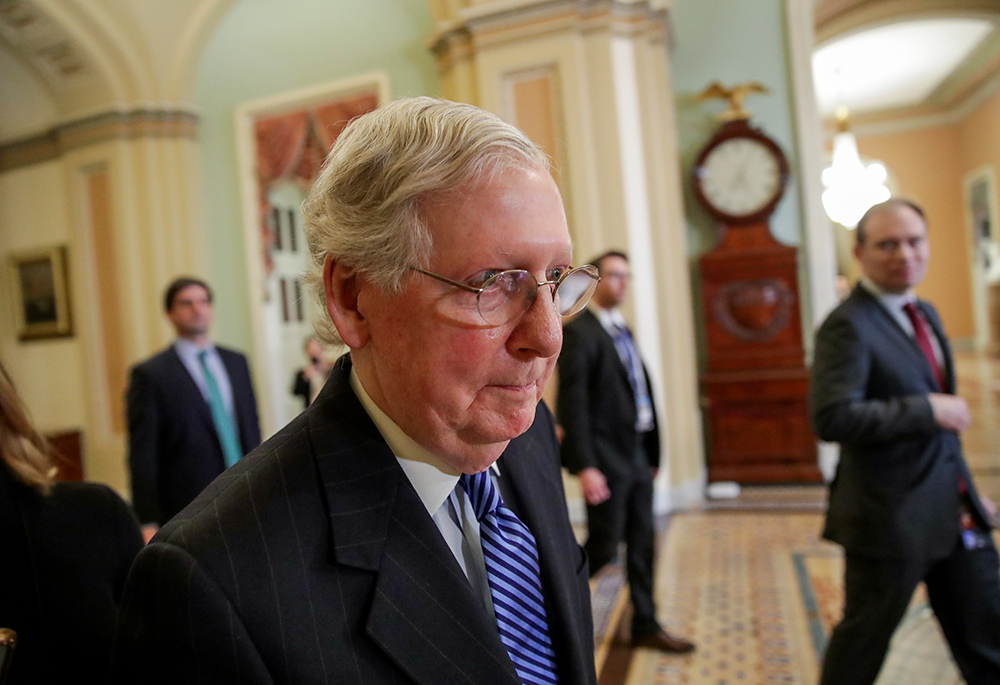

The Republican Party is already drowning in mutual recriminations about their lackluster showing in the 2022 midterm elections. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell publicly criticized former President Donald Trump for his decisive backing of primary candidates who won the GOP nomination but bombed in the general election. "We lost support that we needed among independents and moderate Republicans, primarily related to the view they had of us as a party — largely made by the former president — that we were sort of nasty and tended toward chaos," McConnell said.

Trump had previously called McConnell "a loser for our nation and for the Republican Party" after the Kentucky senator criticized Trump for hosting white supremacist Nick Fuentes and antisemite Kanye West to dinner.

U.S. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., departs following the acquittal of U.S. President Donald Trump Feb. 5, 2020, in the Senate impeachment trial on Capitol Hill in Washington. (CNS/Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)

On the House side, Congressman Kevin McCarthy's ascent to the speakership should have been a cakewalk but instead turned into a chaotic meltdown. A handful of Republican members of Congress, wanting to put a more Trumpian face on the party, refused to play ball with the rest of the GOP caucus. It was not clear whether they really wanted reforms of legislative procedures or simply wanted McCarthy's scalp. Trumpistas inevitably give off a whiff of nihilism, yes?

The Democrats are far more unified at the level of congressional leadership. A remarkable thing happened last year when Speaker Nancy Pelosi; Rep. Steny Hoyer, the longtime No. 2 in the Democratic House leadership; and Rep. Jim Clyburn, the longtime No. 3, all stepped aside to allow a new generation of leaders to emerge. Rep. Hakeem Jeffries was selected as Democratic leader, joined by Rep. Katherine Clark and Rep. Pete Aguilar as No. 2 and No. 3 respectively.

While the right is fighting inside its congressional caucus, the fights on the left have begun on the pages of the nation's leading newspapers. Social critic Thomas Frank recently wrote, "Sizable majorities of Americans desperately want traditional liberal measures like universal health care and economic fairness. But actually, existing liberalism, with its air of upper-crust contempt and its top-down moralism, rubs this deeply democratic nation exactly the wrong way." He correctly diagnosed the utter lack of imagination on the political left.

The New York Times' Michelle Goldberg also thinks the "fever" on the left may be breaking and points to some recent articles by progressive leaders calling for an end to the "left's self-sabotaging impulse." That verdict, though welcome, seems premature.

Advertisement

The other factor that could serve to tamp down any intra-party fights among the Democrats is the expected decision by President Biden that he will run for reelection. If the Republicans have to decide whether they will continue as a Trumpian cult or revert to some version of conservativism, the Democrats' decision about what kind of progressivism they want to embrace could be put off for four years as the party rallies around Biden.

For both parties, the intra-party struggles have an ideological aspect, and Catholic social teaching would serve both parties well as a counterpoint to their worst tendencies. For Republicans, their economic libertarianism, which unites the Trump and anti-Trump right, seems relegated to the background and the primary issue is whether the GOP is to embrace the anti-democratic belief that might makes right. Catholicism, which has learned to live with every form of government through the centuries, has never embraced the crude authoritarianism embodied in that dictum.

For Democrats, the question is whether an economics rooted in the common good can be their calling card or if they will embrace the culture wars from the left, leading with issues of sexual and racial identity. Again, Catholic social teaching would point them in the right direction, away from the culture wars and towards the articulation of the kind of social democracy that shaped the New Deal and the Great Society programs that remain the most popular and potent expression of the common good in American political life.

The second political dynamic we can expect this year is stalemate. Morally clamant issues like immigration reform will not even be raised because the prospect of achieving anything is miniscule. The decision by Rep. Kevin McCarthy to improve his chances at becoming speaker by lowering the threshold needed to force a no-confidence vote puts him on a very short leash, even if he wins. Previously, half the caucus had to vote to bring a motion to "vacate the chair." Now, apparently, one member can force that most destabilizing vote any legislative chamber can face.

Members kneel in prayer prior to a 12th round of voting for a new Speaker of the House of Representatives, on the fourth day of the 118th Congress at the U.S. Capitol Jan. 6 in Washington. (CNS/Reuters/Evelyn Hockstein)

This kind of procedural dynamic seems far removed from the moral calculations flowing from Catholic social teaching. But just as Washington Archbishop Patrick O'Boyle denounced the use of the filibuster to prevent civil rights legislation in the 1960s, so too in this decision to empower a small fringe of extremists, significant moral issues are in play. Government does not exist to keep this man or that woman in power, but to work for the common good of a people. Giving someone like Rep. Matt Gaetz a parliamentary weapon to prevent the kind of compromises our country needs on many issues, from immigration reform to gun control, is a variety of moral abdication.

Come the autumn, when the Congress will face some must-pass legislation, such as voting to raise the nation's debt ceiling and to fund the government, the usual bipartisan consensus that makes those difficult votes possible may not exist. Catholic social teaching is clear on this point: Failing to govern does not serve the common good.

Finally, the economy, migration and Ukraine will all play a large role in the nation's political life this year, and all three resist easy political or policy solutions. Our Catholic social teaching nonetheless offers guidance.

The economy will continue to struggle with inflation and there is little the president or Congress can do about it. At a deeper level, the kinds of policy changes to the tax code that might ameliorate the gross income inequality that afflicts our society are not going to happen. The best we can hope for is that state and municipal governments will follow the lead of the last Congress in voting for programs that help convert our economy to sustainable energy sources, address poverty and homelessness, and commit to infrastructure projects that are sorely needed. America needs to invest in its own future more than it needs to subsidize Wall Street. Catholic social teaching is clear here: An economy is measured by how he treats the poorest, not the wealthiest, of its citizens.

Catholic social teaching is clear on this point: Failing to govern does not serve the common good.

No political will exists to confront the migration crisis at our southern border, or the problems within our border. It is shocking that DACA recipients still are unsure what their future holds. It is shocking that undocumented workers can be so easily exploited in the labor market. And it is shocking that we have not established a policy for handling the refugee crisis at the border. Worst of all for liberal Catholics, one of our own, Joe Biden, has been president for two years and we have seen no leadership from the White House on this issue. None. Again, the teaching of the church is clear: We follow a savior who was himself a refugee as a child, and both the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures are clear on the moral obligation to welcome the stranger.

The outcome of a war depends on the vagaries of battle as well as on political decisions made in legislative chambers. The brave people of Ukraine are defending not only their homeland but the principle that might does not make right. They are defending democracy and decency. They are defending the proposition that a nation should be free to choose its own allies and its own future without being invaded by a powerful neighbor that disapproves of those choices. Our task in America is easy: The people of Ukraine have asked us for military and humanitarian aid and we have it within our power to fulfill that request. All the requirements of just war theology have been met. Indeed, the right to protect counsels us to aid the Ukrainians in their hour of need.

Those are the stories that I will be looking at in the new year. And, there is one more, admittedly less important, reality about the estuary where politics and religion intertwine: Tomorrow, my newsletter starts! Make sure you sign up to receive it by clicking here. Whatever happens in 2023, you know you can read analysis drawn from an explicitly Catholic and liberal perspective here.