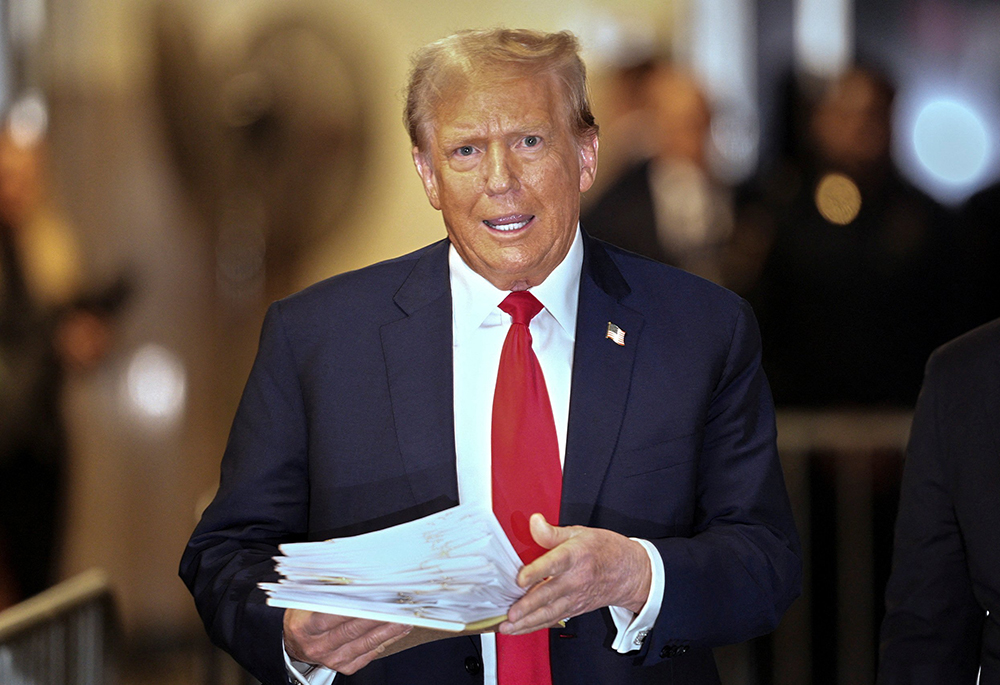

Republican presidential candidate and former U.S. President Donald Trump leaves Manhattan Supreme Court in New York City April 23, the sixth day of the hush money trial against him. (OSV News/Curtis Means, Pool via Reuters)

We're all getting ready for the three-day weekend that unofficially kicks off the summer: vacuuming the pool, buying chicken nuggets for the kids who won't eat anything else, mowing the lawn. Why shouldn't the jury in former president Donald Trump's New York trial get the weekend off too? They return to court on Tuesday for closing arguments.

For five weeks, the jury has listened to a series of sordid tales. The former president is accused of having his attorney at the time, Michael Cohen, pay hush money to former porn actor Stormy Daniels and then misrepresent the reimbursement as payment for legal fees, all of it set down on federal election campaign forms, which make the alleged subterfuge illegal.

There are no cameras in the courtroom so we must rely on transcripts and the impressions of those in the media who do get into the courtroom. God sent me a small mercy when I was away from home during Daniels' testimony and missed it entirely. (Thank you, Jesus.) The jury had to sit through Daniels' vivid account.

The jury has learned that some scurrilous tabloid editors "catch and kill" a story, buying the exclusive rights only to make sure the story never sees the light of day, and whether or not that is what happened in this case. Trump's friend, David Pecker, the former publisher of the National Enquirer, testified that Trump was mostly concerned about the negative impact the stories about him and Daniels (as well as Karen McDougal, another woman who was allegedly paid hush money to conceal her relationship with Trump) would have on Trump's presidential bid, which is a crucial piece of the legal puzzle. It is not a crime to pay someone money to keep quiet about an affair if your only goal is to keep your spouse from learning about it. It becomes a crime when it is an unreported campaign expense.

The jury certainly got to know all about Michael Cohen. It is shocking that the prosecution brought a case that rests so heavily on the credibility of Cohen, a man whose lies are often three-deep, who loved working for the Donald until he didn't, and who admitted during cross-examination that he had stolen money from the Trump organization, accepting a reimbursement of $50,000 from Trump when he only paid $20,000 to a technical service company to rig polling data in Trump's favor.

Advertisement

On that last point, as Aaron Blake pointed out in The Washington Post, Trump's attorneys may have been too clever by half. Yes, the fact that Cohen admitted to stealing further undermined his credibility, but it confirmed the fact that Trump was in the habit of reimbursing Cohen for things that were unseemly. As Blake noted, "playing this up would sure seem to substantiate the idea that Cohen was being reimbursed for at least something — that this wasn't just some normal legal retainer, as the Trump legal team has sought to cast it."

The whole trial has been one tawdry or salacious detail after another, all of it tied to the prosecution's difficult-to-follow, three-step legal theory. The prosecution's case shifts the misdemeanor charge of falsifying business records under New York law, and turns it into a felony by first linking it to another misdemeanor under New York law §17-152, which bars "conspir[ing] to promote or prevent the election of any person to a public office by unlawful means," and finally linking the law to federal election law, which makes the whole thing a felony.

If the jury follows that legal logic, and if it finds Cohen credible, then they should deliver a guilty verdict. Because our elections are often decided by low-information voters, a guilty verdict in any of the cases against Trump could, and should, end his chance at regaining the White House. But those are some pretty big ifs on which to hang the future of the republic.

Presidents have engaged in dreadful behavior before. Many had mistresses, some were corrupt, others had monstrous blind spots on important moral issues like slavery. At least they all had the decency to do it before the advent of social media and cable news. The "end of regime" sensibility of our political discourse may actually just be an "end of Trump" sensibility.

Unless he is acquitted.