U.S. President Joe Biden speaks next to Shawn Fain, president of the United Auto Workers, as he joins striking UAW members on the picket line outside the GM's Willow Run Distribution Center in Belleville, Michigan, Sept. 26. Biden became the first known sitting U.S. president to join a labor strike. (OSV News/Reuters/Evelyn Hockstein)

President Joe Biden went to the General Motors parts distribution warehouse in Van Buren Township, Michigan, where he joined the United Auto Workers' picket line.

"The fact of the matter is that you guys, the UAW, you saved the automobile industry back in 2008 ... you made a lot of sacrifices," Biden said. "You gave up a lot. And the companies were in trouble. Now they're doing incredibly well and guess what? You should be doing incredibly well."

Biden was the first sitting president to join a picket line. In fact, there have not been a lot of major strikes in recent years, certainly not when compared to the postwar era. We think of the late 1940s and 1950s as times of social cohesion and even conformity, but they were times of frequent strikes. Almost 5% of the entire workforce was on strike at some point during the year 1952! Those years also witnessed the most widespread prosperity in U.S. history, with a growing middle class, relatively low income inequality, and substantial wage growth. We could do with some more conformity like that!

The UAW strike is not the only example of much-needed labor activism. According to Politico, the Union of Southern Service Workers is attempting to organize low-wage service workers throughout the South. The International Association of Machinists just scored two organizing victories in New Jersey and Massachusetts. Screenwriters reached a tentative deal in Hollywood, but actors are still in negotiations. On the other hand, efforts to extend last year's first-ever organizing win at Amazon have stalled, as The Guardian reports.

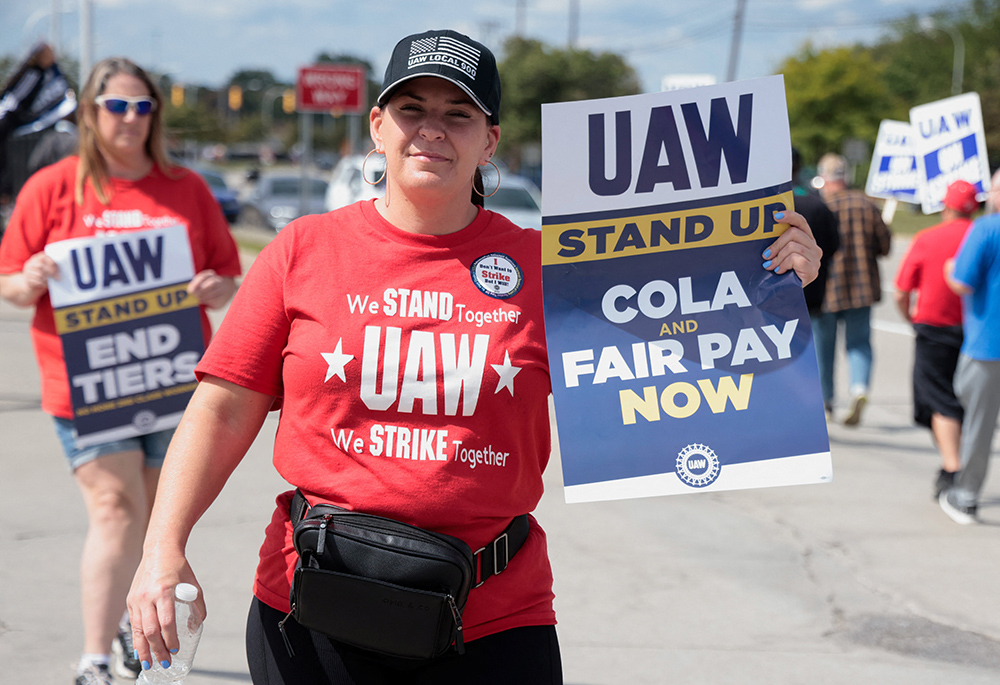

Striking United Auto Workers walk the picket line outside the Ford Michigan Assembly Plant in Wayne, Michigan, Sept. 15. (OSV News/Reuters/Rebecca Cook)

In 2012, Jordan Weissmann published a famous article in The Atlantic entitled "60 Years of American Economic History, Told in 1 Graph." It showed how the lowest quintile did best in the '50s and '60s and how, starting in the '70s, the decrease in the percentage of the workforce in unions combined with the rise of the financial sector to flip the economic rewards of growth. The top quintile started doing best in the 1980s and that trend has not changed.

The economic disenfranchisement of the middle and working classes was the most critical component, though not the only one, in the societal alienation that Donald Trump has figured out how to harness into the most dangerous political movement in American history.

Trump also went to Michigan this week, but he just can't break his cocoon of narcissism long enough to demonstrate anything like genuine solidarity with workers. As The Washington Post reported, "Trump offered his support to striking members of the United Auto Workers but demanded the union's official endorsement or else warned of their imminent extinction." Good luck getting between the UAW rank-and-file and union president Shawn Fain at any time, but especially in the middle of a strike. The only person who would think it possible to cause such a breach would be a real estate guy with a track record of treating workers shabbily, someone like Trump.

While inflation has been the most visible economic reality of the past few years, the fact is that low wage workers have done better in the past three years than other workers, partly because of the shape of the post-COVID economy, and partly because of Biden's economic policies.

Advertisement

If those gains are to be consolidated, we will need to exercise solidarity with workers. Wednesday, I was at a hotel in New York which had no restaurant or even coffee service in the morning. Finding workers in traditionally low wage service jobs has become very hard, pushing up wages in most places and, in others, forcing businesses to adapt. I asked the manager where I could grab a cup of coffee at 6:30 in the morning and he said there was a Starbucks next door. "Is it union?" I asked. "I don't think so," he replied. I went to a bodega a few blocks away. The coffee might not have been as tasty, but if enough people start seeking alternatives to Starbucks, the corporate bigwigs will notice.

If you are planning a meeting, do you make sure it is booked at a union hotel? The Fair Hotel guide, sponsored by Unite Here, which represents hotel workers, is an exceedingly easy way to make sure the hotel you are planning to use is not in a labor dispute, or at risk of such a dispute.

Catholics need to stand with the working people of this country — and of other countries. Trade deals like NAFTA managed to harm workers both in the developed world and in the underdeveloped world. Trade pacts usually have language that seemingly protects workers in underdeveloped countries, but when you read the fine print, labor disputes must be resolved in U.S. courts and there are not a lot of workers in Malaysia or Vietnam or El Salvador who can afford a New York law firm.

Starting with Rerum Novarum in 1891, the magisterium has taught that workers have a right to organize. That teaching has been reaffirmed by Popes Pius XI, John XXIII, Paul VI, John Paul II, Benedict XVI and Francis. That is a lot of popes. Some bishops in the U.S. understand that unions are schools of solidarity. Most don't. Cardinal Blase Cupich, whose talk this week (Sept. 26) at Fordham University focused on creating an "integral ethic of solidarity," is the exception. He should be the rule.

Seeing the second Catholic president stand with the workers outside the GM distribution center was a reminder of the once vibrant alliance between the Catholic Church and organized labor. That alliance was both a herald to and an epitomization of a healthy society in which solidarity was understood to be more important than profit. However disappointed Catholics are in Biden's immigration and abortion policies, when it comes to unions, he does the teachings of his church proud.