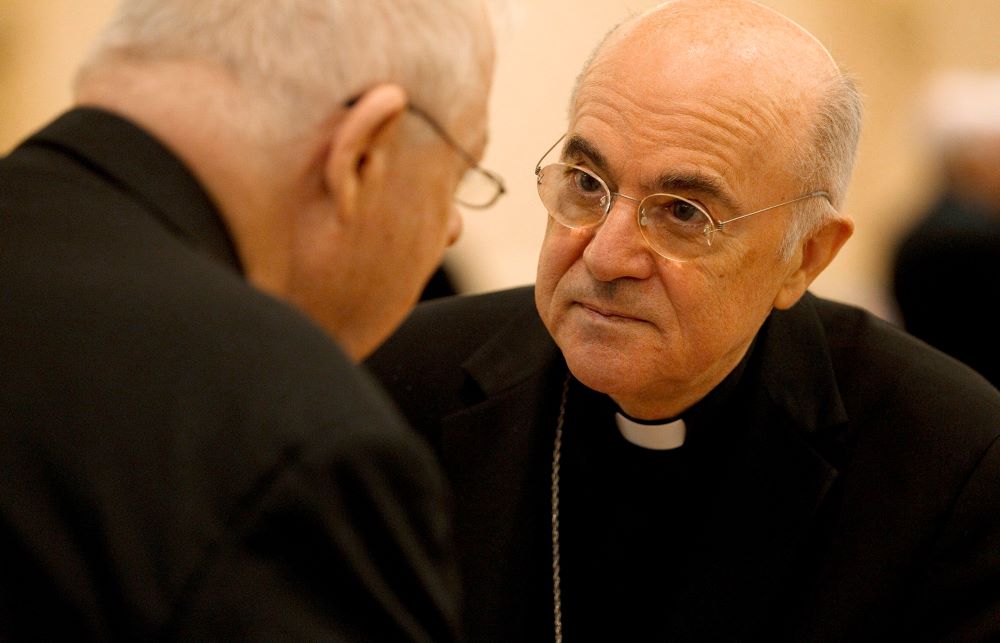

Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, then apostolic nuncio to the United States, talks with a U.S. bishop during the bishops' meeting in Baltimore in this Nov. 13, 2012, file photo. (CNS/Nancy Phelan Wiechec)

The charge of schism against Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, the disgraced former nuncio to the U.S., is a consequential event. It is one thing to wrestle with this or that teaching of the church, to like or dislike this pope or that. But to so question and undermine the authority of the church itself such that you find yourself charged formally with schism, this is a grave thing.

There can be little doubt that Viganò is guilty of the charge. You only need to follow his Twitter feed to recognize the archbishop has become unhinged. And his criticisms are not just directed at Pope Francis. Viganò now routinely questions the teachings and authority of the Second Vatican Council, citing prior papal and conciliar teachings. By definition, that entails deploying those prior teachings out of context — to say nothing of the hubris required to insist one is right and the more than 2,000 bishops who attended Vatican II were wrong.

This is not just schismatic; it is bizarre. It would be like challenging a decision of the federal government today because it violated the Articles of Confederation. Who cares? The articles gave way to the constitution and Vatican I gave way to Vatican II. Better to say, Vatican II incorporated the teachings of all prior councils into its own teachings. If you attack Vatican II, you are attacking all previous councils as well.

Efforts to find the appropriate stance to take vis-à-vis Viganò will have all the elegance of a game of Twister. My former NCR colleague John Allen correctly noted the significance of Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Pietro Parolin's comments about Viganò. "I always appreciated him as a great worker very faithful to the Holy See, in a certain sense also an example," said Parolin, obviously referring to an earlier time in Viganò's career. "When he was apostolic nuncio he worked extremely well, I don't know what happened."

Allen predicted these comments might provide some cover for those U.S. bishops who, when Viganò issued his demand that Francis resign, issued statements of support for Viganò and not for Francis. Allen might be correct, but it would be a mistake if those bishops who were so quick to defend Viganò are permitted to escape moral scrutiny for their statements.

"Parolin, however, has offered a reminder that perceptions of Viganò in 2018 were different than today," Allen writes. "Back then, most US bishops simply recalled him as a former Vatican official and a reasonably effective ambassador to the States. They had no way of knowing what he would later become, nor were many of them eager in the immediate wake of the [former Cardinal Theodore] McCarrick revelations to be seen as dismissing any accusation, no matter whom it involved."

No way of knowing? It is true that Viganò has become unhinged in ways that were difficult to imagine. His attacks on the Second Vatican Council represent a radicalization that none of us could have predicted. But we knew a lot about Viganò in 2018, and Parolin's comments should not provide anyone with a pass.

Efforts to find the appropriate stance to take vis-à-vis [Archbishop Carlo Maria]Viganò will have all the elegance of a game of Twister.

We knew that Viganò had a streak of narcissism, with a dash of paranoia, back in 2012 when the Vatileaks scandal exploded. We learned that when Pope Benedict XVI had appointed Viganò as nuncio to the U.S., Viganò complained that he should be allowed to stay in Rome to pursue corruption within the Vatican, that he was the only man for the job and that his removal was the work of his enemies. The complaint came in an 11-page letter to the pope which, as one Vatican wag commented, "was 10 pages too long." When informed the pope had refused his request to stay, Viganò sent a second, seven-page letter. That was seven pages too long.

We knew that Viganò was willing to sabotage Francis' successful trip to the U.S. in 2015 when Viganò decided to introduce the pope to Kim Davis, the Kentucky clerk who went to jail because she refused to allow her office to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples. Viganò told the pope she was a conscientious objector, which was false. As I noted at the time: "Davis lost her right to consider herself a conscientious objector when she forbade other people from issuing the marriage licenses she did not wish to issue herself. Davis was not jailed for practicing her religion. She was jailed for forcing others to practice her religion." News of the meeting dominated what should have been upbeat coverage of the pope's trip.

Most of all, as soon as we read Viganò's 2018 screed calling on the pope to resign, we knew that this was no disinterested testimony against the Vatican's willful ignorance of former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick's crimes. If that had been the case, the target would have been Pope John Paul II who had promoted McCarrick three times, not Francis, who was elected pope seven years after McCarrick retired.

Advertisement

No, the screed was evidence of a putsch. The timing of the document's release, while the pope was leaving Ireland, and the choice of the National Catholic Register's Edward Pentin as the journalist to break the story, these were calculated choices. The New York Times reported that Viganò had consulted Napa Institute founder Timothy Busch about the letter, a charge Busch later denied. Busch doesn't know much about authentic Catholic theology or canon law, but even he should have known that calling for the pope to resign, when the allegations do not even make sense, goes against everything we Catholics believe about the unique office of successor of St. Peter.

Busch may be able to plead ignorance, but what about the 40 or so bishops who rushed out with statements supporting Viganò? Will they, now, at long last, withdraw their previous statements of support?

John Allen is wrong. Everyone knew who Viganò was. But, if Allen were right, and Parolin has thrown a lifeline to the U.S. bishops who sided with Viganò, will they grab it? If not, what does that say about their own indifference to the danger of walking down a schismatic path?