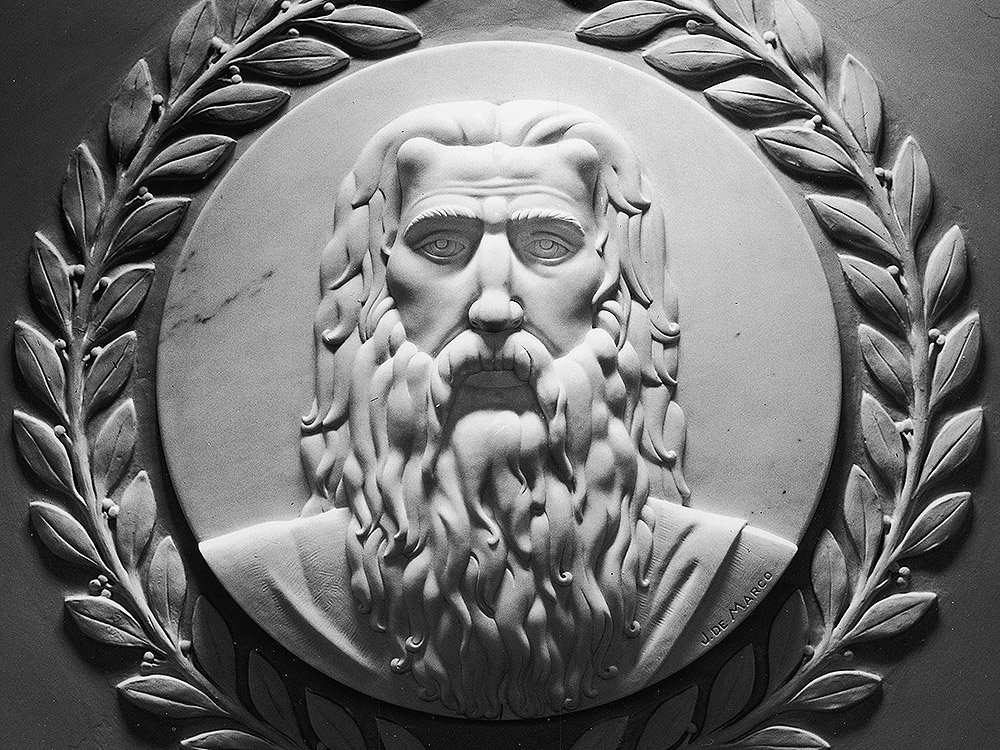

Moses is among the marble bas-relief portraits of lawgivers that hang in the U.S. House of Representatives chamber in the Capitol building in Washington, D.C. (Wikimedia Commons/Architect of the Capitol)

The state of Louisiana has decided that the Ten Commandments should be posted in every classroom in the state. Wouldn't you know, and in response to the decision, all hell broke loose.

At The Hill, Southern Methodist University professor of religious studies Mark Chancey denounced the decision as "alarming." He recalled the incident in 1859 when 11-year-old Thomas Wall, a young Catholic student, refused to recite the Protestant version of the Ten Commandments and had his hands beaten. Surely, such an incident can and should be included in whatever curriculum is devised to explain the historical significance of the Commandments.

"Permanently posting the Ten Commandments in every Louisiana public-school classroom — rendering them unavoidable — unconstitutionally pressures students into religious observance, veneration, and adoption of the state's favored religious scripture," fretted the American Civil Liberties Union in a complaint filed to block the new law.

At Religion News Service, Mark Silk is right to chuckle at these religiously motivated politicians bending over backward to make the case that the Ten Commandments is of secular significance: The new law also requires posting of the Mayflower Compact, the Declaration of Independence and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, but the Ten Commandments are difficult to disentangle from their religious significance.

But while it is not true to call America a "Christian nation," for most of its history it was a nation of Christians, and they certainly were motivated in their understanding of law in part by the tablets Moses brought down from Sinai.

Everybody needs to take a deep breath and relax.

When you enter the U.S. House of Representatives chamber in the Capitol building, you will find 23 relief portraits over the gallery doors, each one representing some of the great lawgivers in Western civilization. Blackstone, Hammurabi, Justinian, Napoleon are all there. So is Moses. And the country hasn't fallen apart. The Congress has not authorized an Inquisition.

There was an underlying assumption that stalked church-state jurisprudence in the past many decades: that secularity equals neutrality. That assumption is deeply flawed.

One of the things that is happening in our legal system is that decisions made by previous courts regarding many issues are being reevaluated. You can like that or not like it, but one thing is certain: The church-state jurisprudence of the Vinson, Warren and Burger courts did not come down from Sinai.

In its 1980 decision in Stone v. Graham, the U.S. Supreme Court barred the Commonwealth of Kentucky from posting the Ten Commandments in its schoolrooms. The court stated: "If the posted copies of the Ten Commandments are to have any effect at all, it will be to induce the schoolchildren to read, meditate upon, perhaps to venerate and obey, the Commandments. However desirable this might be as a matter of private devotion, it is not a permissible state objective under the Establishment Clause."

One is tempted to commend anything that might induce a young person to meditation in this noisy, social-media-driven world, but that is not the point that is most salient. And the Supreme Court had previously discarded the Lemon test the court used to decide Stone v. Graham. The point is that there was an underlying assumption that stalked church-state jurisprudence in the past many decades: that secularity equals neutrality. That assumption is deeply flawed.

One of the fundamental dynamics that James Davison Hunter explains in his recent book, Democracy and Solidarity: On the Cultural Roots of America's Political Crisis (which I recently reviewed here and here), is the breakdown of what was once a shared understanding of the national mythos, a breakdown into two rival worldviews with fundamentally different objectives. One measures national success by its ability to maximize individual autonomy and the other continues to insist on the need for a transcendent anchor to which individuals and society should align themselves.

At the level of public intellectuals, this was a foundational difference between John Dewey and Reinhold Niebuhr, and later between Richard Rorty and Richard John Neuhaus. At the popular level, these differences were and are more blurry. In between the people and the philosophers, special interest groups increasingly see the differences not as something to be negotiated but as a conflict to be won, a zero-sum game, a battle for the soul of America.

Advertisement

In his speech to the British Parliament in 2010, Pope Benedict XVI said: "This is why I would suggest that the world of reason and the world of faith — the world of secular rationality and the world of religious belief — need one another and should not be afraid to enter into a profound and ongoing dialogue, for the good of our civilization."

Those are wise words with which people who care about the future of American democracy should wrestle. They were expressed in greater depth in the fascinating public discussion then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger had with Jurgen Habermas and published under the title The Dialectics of Secularization: On Reason and Religion.

Pope Francis also spoke to the need to reflect more deeply on the relationship of the sacred and the secular when he addressed the U.S. Congress in 2015.

"Yours is a work which makes me reflect in two ways on the figure of Moses," Francis said to the assembled members of Congress. "On the one hand, the patriarch and lawgiver of the people of Israel symbolizes the need of peoples to keep alive their sense of unity by means of just legislation. On the other, the figure of Moses leads us directly to God and thus to the transcendent dignity of the human being. Moses provides us with a good synthesis of your work: You are asked to protect, by means of the law, the image and likeness fashioned by God on every human face."

The walls of the U.S. Capitol did not come crashing down when Francis invoked the memory of Moses. The republic can withstand, and might even benefit, from calling more attention to the role the Ten Commandments played in the development of Western civilization generally and American self-identity in particular.

I am not sure I trust these delicate issues to the rough-and-tumble of Louisiana politics, but I am quite certain that fighting a new culture war battle over the placement of the Ten Commandments on the walls of schools is a fool's errand.

We need to stop fighting the culture wars and, instead, set ourselves to the hard work of forging a culture capacious enough to embrace both religion and reason, the transcendent and the secular, Americans who believe and those who don't.