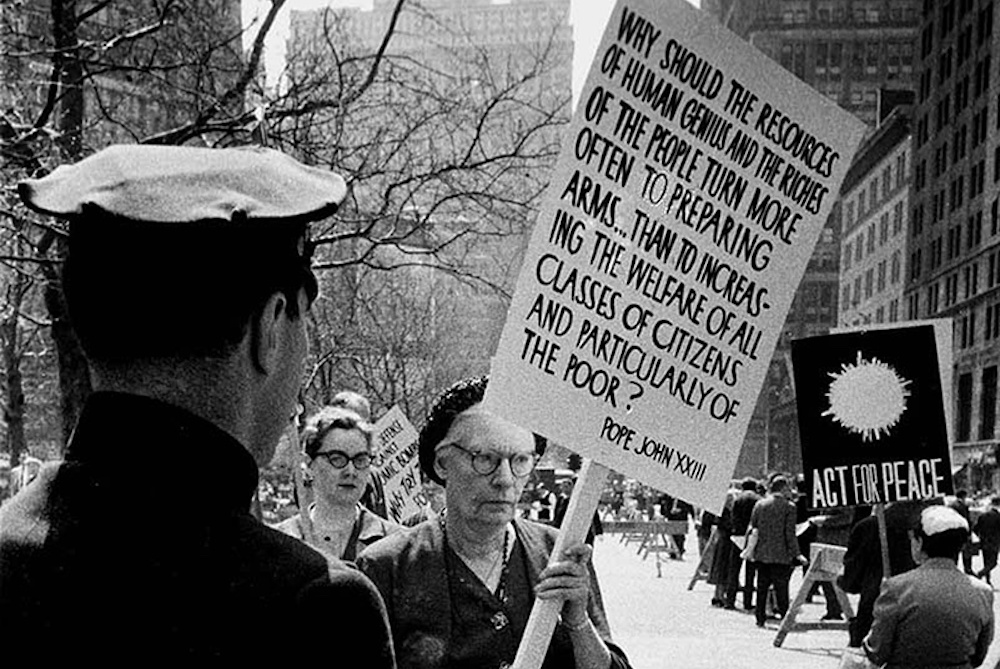

Still shot from the "Revolution of the Heart: The Dorothy Day Story," a film by Martin Doblmeier (CNS/Courtesy Journey Films)

I first stumbled upon the Catholic Worker movement shortly after I graduated high school. Having taken several months to travel the country, I lived for a few weeks in a blighted section of Baton Rouge at Solidarity House, one of more than one hundred Catholic Worker houses of hospitality. Every night, the two ex-Franciscan founders of the community served rice and beans to 30 people in the neighborhood. They offered lodging to a handful of otherwise-homeless men while also frequently picketing against the death penalty. Their work was inspired by the cofounders of the Catholic Workers: Peter Maurin, a Catholic radical from France, and Dorothy Day.

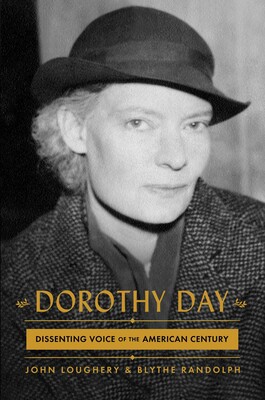

Four decades after her death, Dorothy Day — journalist, political activist and Catholic convert — is getting the attention she deserves. John Loughery and Blythe Randolph's Dorothy Day, Dissenting Voice of the American Century, backed by a major publisher, now eclipses William Miller's out-of-print biography as the fullest, lengthiest story of the woman the Catholic Church is currently considering for canonization. The work is clearly a labor of love, deeply researched by two experienced biographers. In the nearly 400-page volume, we learn the story of a woman who doggedly embraced service to the poor and life in community, active nonviolence and voluntary poverty. While the book is overly detailed at times — those looking for a shorter introduction to Day might refer to Jim Forest's All Is Grace — the volume is well worth reading in order to grapple with this astonishing life.

Born in Brooklyn in 1897 to a secular middle-class family, Day would drop out of college at the age of 17 to write for leftist publications in New York. Covering strikes, protests and the plight of the unemployed by day, by night she was drawn into the anguished orbit of dreamers poets, and artists, enjoying late night revelry at the taverns in Greenwich Village. (One observer was "admiringly astounded that a woman could consume so much alcohol.")

Though over the years much has been made about Day's pre-conversion life, Randolph and Loughery provide the fullest account of those wild, bohemian days, which include Day's abortion, divorce and at least one suicide attempt. But as the authors make clear in their lively stories, Day's impressive and tenacious commitment to resistance also took root during that time. Once, sentenced to 30 days in jail over a protest for women's suffrage, an infuriated Day sank her teeth into the warden's hand, resulting in her twice getting slammed onto a metal bench. The following year, she was struck in the ribs by a policeman on her way to a mass peace protest.

Despite the fact that she described herself as a "dedicated atheist," Day gradually began to veer from the accepted New York Village orthodoxy, which dismissed the "superstition" of religious institutions like the Catholic Church. Mysteriously, Day often felt the impulse to duck into church to pray. Slowly, she was compelled by the call in William James' The Varieties of Religious Experience to become "poor in order to simplify and save [one's] inner life."

But it was the experience of joy during her pregnancy and the birth of her daughter, Tamar, in 1926, that finally led Day to join the Catholic Church. "Now she was Dorothy Day, a Roman Catholic," the authors write. "And that designation, among her secular and highly political circle of friends and relatives, defied reason and caused noticeable discomfort." Her conversion was a lonely one.

But, as Randolph and Loughery perceptively note, Dorothy Day was "a woman often on the end of serendipitous encounters." In December 1932, while covering the Hunger March in Washington, D.C., Day prayed for a way to unite her passion for justice with her deepening faith. Upon her return, Peter Maurin was waiting for her. A philosopher and peasant 20 years her elder, Maurin was a man who would change Day's life forever. He talked, nearly breathlessly, about the state of the world, the state of the church, the saints, a "green revolution" to get back to the soil, hospitality to the impoverished, and his plans for a Catholic newspaper. He had a vision to revolutionize society, and she had an answer to her prayer.

Advertisement

On May Day 1933, 2,500 copies of The Catholic Worker were published, and soon the two were housing the homeless. They didn't register as a non-profit; they were simply Catholics doing their Christian duty. And the hungry, as well as a steady stream of like-minded idealists, kept showing up at their door. Other communities sprung up across the country, and, by 1938, subscriptions to the paper peaked at 190,000.

As the authors make clear, Day was never one for popular stances. She was neither a liberal nor a conservative. Though she protested with the suffragists, she was an anarchist who never voted, believing, with author Jack London, that both political parties were "creatures of the Plutocracy." During World War II, Day maintained an ardent pacifist stance, which resulted in the FBI opening a file on her that would span three decades. Her public critique of the war troubled even many within the movement, which suffered: By 1942, circulation had dropped to 50,000.

Yet life at the Catholic Worker, however precarious, continued. Over the next few decades, Catholic Workers were at the forefront of the protests against nuclear air raid drills in the 1950s and were among the first to publicly burn draft cards during the war in Vietnam. And there was always the soup line. In a 1973 interview with Bill Moyers, Day told of a woman who was dumped on the steps of the Catholic Worker covered with lice and reeking of urine and excrement. Randolph and Loughery remark, "That was what the Catholic Worker had to deal with, she wanted people to know."

Though Day may ultimately become canonized as a saint in the Catholic Church, the authors are clear that this doesn't mean she was perfect. Day's daughter, Tamar, for example, was often not the top priority for Day; Day was often gone on speaking tours, not only to spread the message of the movement, but also to get away from the overwhelming demands of hospitality. One long-time Catholic Worker joked about Day to the new Catholic Worker volunteers: "Oh, once you get to know her, she's just like any other crabby old lady."

Day never relented from her Catholic radicalism. Once, Day was asked by a Fordham University student whether her movement might be more successful if she eased up on her demanding ideals, which, the student noted, were "kind of hard to take." Day replied that the Gospels, too, are "kind of hard to take."

Nearing the end of Day's life in 1980, many wondered what would happen to the Catholic Worker movement. One young Worker once commented, "We have Dorothy now, but we will always have the Gospel." In part thanks to biographies like Randolph and Loughery's, we will continue to have the example of Dorothy Day, whose life demonstrated the subversive way of the Gospels in our times.

The funeral procession for Dorothy Day makes its way to the Church of the Nativity in New York Dec. 2, 1980. The Archdiocese of New York sold the decommissioned Church of the Nativity in 2020 to a Los Angeles-based real estate firm for $40 million. This was the parish Day attended. (CNS/Tom Lewis)

[Eric Anglada lives on St. Isidore Catholic Worker Farm and works for the Sinsinawa Dominicans, both in southwest Wisconsin.]