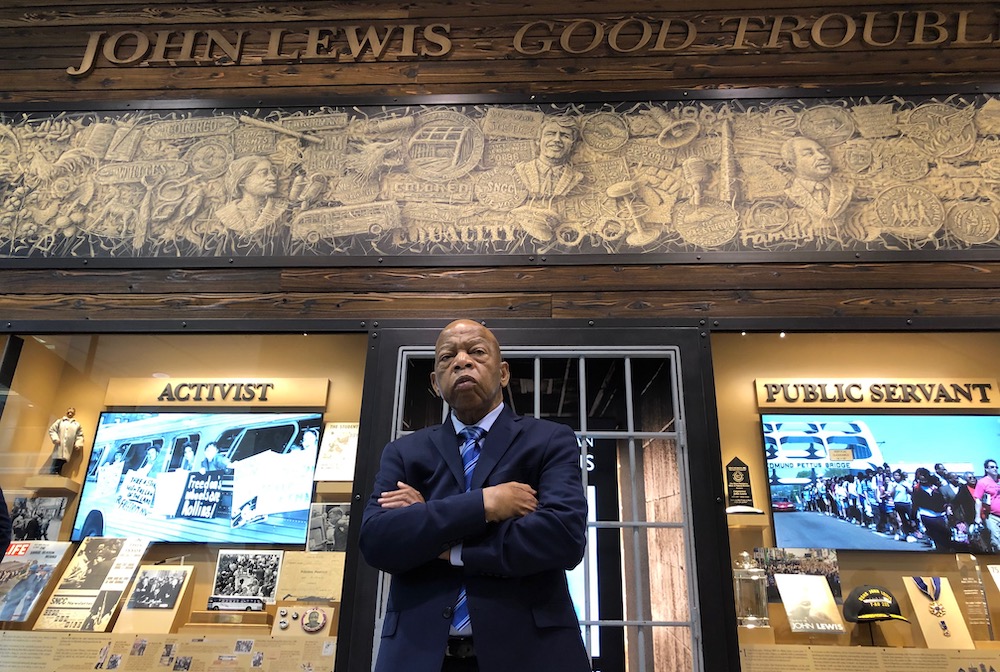

John Lewis in "John Lewis: Good Trouble," a Magnolia Pictures release. (Courtesy of Magnolia Pictures)

Homegoing celebrations for revered civil rights leader and Democratic Georgia Congressman John Lewis, who died July 17 at 80 from pancreatic cancer, will likely increase interest in "John Lewis: Good Trouble."

Three crises added resonance to these well merited encomiums for Lewis from former presidents, civil rights leaders and ordinary people.

There were national racial justice protests condemning the May 25 killing of 46-year-old African American security guard George Floyd apparently by four Minneapolis policemen. And the greatest public health crisis facing the country in more than a century precipitated the most significant economic downturn since the Great Depression.

Over the course of six extraordinary late July days, memorial ceremonies in some places where Lewis left his indelible mark — his hometown of Troy, Alabama, and Montgomery and Selma, Alabama, Washington, D.C., and finally Atlanta — bound us in our national grief for this exceptional soul. But, "the boy from Troy," as Dr. Martin Luther King called him, fittingly had the last word.

In a remarkable letter, published in The New York Times the day Lewis died, the representative from Georgia's 5th Congressional District reminded us to: "walk with the wind, brothers and sisters, and let the spirit of peace and the power of everlasting love be your guide."

Those looking to "Good Trouble" to investigate Lewis' life more fully will likely be disappointed. Not without value and its charms, the modest and oddly cursory documentary is streaming online. CNN Films will premiere the documentary on its network Sunday, Sept. 27, 9-11 p.m.

Dawn Porter, director of "John Lewis: Good Trouble," a Magnolia Pictures release (Courtesy of Magnolia Pictures/© Henny Garfunkel)

Dawn Porter directed the film. Some may recall Lewis was featured in her uneven, but often absorbing four-hour 2018 docuseries "Bobby Kennedy for President" about the late, former New York senator's storied campaign to win the Democratic Party's 1968 presidential nomination.

"Good Trouble" is on a smaller, more intimate scale than that docuseries. An interview with the congressman, reflecting upon archival civil rights footage, shapes the documentary. Although filmed before Lewis' December 2019 announcement of his cancer diagnosis, the congressman's imminent death is uppermost in viewers' minds, even if it isn't in his.

Compelling him to look back, Porter understands her subject in his late 70s is more interested in moving forward because, he says "there are forces trying to take us back." Employing a cinema verité style, the documentarians accompany "the conscience of Congress" as some referred to him, on multiple sojourns.

At Lewis' Atlanta home, he collects his morning paper and gears up for the pivotal 2018 mid-term elections, which saw the Democrats take back the House of Representatives from the Republicans.

Reviewing the headlines, the congressman echoes what President Barack Obama said at the recent Democratic National Convention. "My greatest fear," Lewis says, "is one day we may wake up and our democracy is gone." "As long as I have breath in my body," he says, he will work to ensure our democracy doesn't evanesce.

Advertisement

During that election season, Lewis crisscrosses the South, bolstering first-time candidates. At a rally in central Texas for congressional candidates and Senate aspirant and former Democratic presidential candidate Beto O'Rourke, Lewis is the featured speaker.

He repeats the well-known tale, which gives the documentary its title. The third of sharecroppers Willie Mae and Eddie Lewis' 10 children, growing up in Troy in Pike County in southeast Alabama, the civil rights leader asked his parents about "white" and "colored" signs, and they admonished him "not to get into trouble."

At 17, Lewis, seeking his help to get into local college Troy State, which he felt unfairly denied him admission, met Dr. King. Plotting with King to address this injustice became the catalyst for Lewis "to get into good trouble." By which he means, he tells the central Texas crowd: "When you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, say something, do something."

"Good Trouble" works best when it underscores Lewis' abiding commitment to non-violence and voting rights. In one of the film's more evocative moments, the congressman says, "I'm seeing footage I've never seen before."

He refers to archival film of Vanderbilt University Divinity School Professor Dr. James Lawson leading a workshop in 1960 in Gandhian non-violence for local university students, including Fisk University students Lewis and his good friend Bernard Lafayette, who became leaders in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

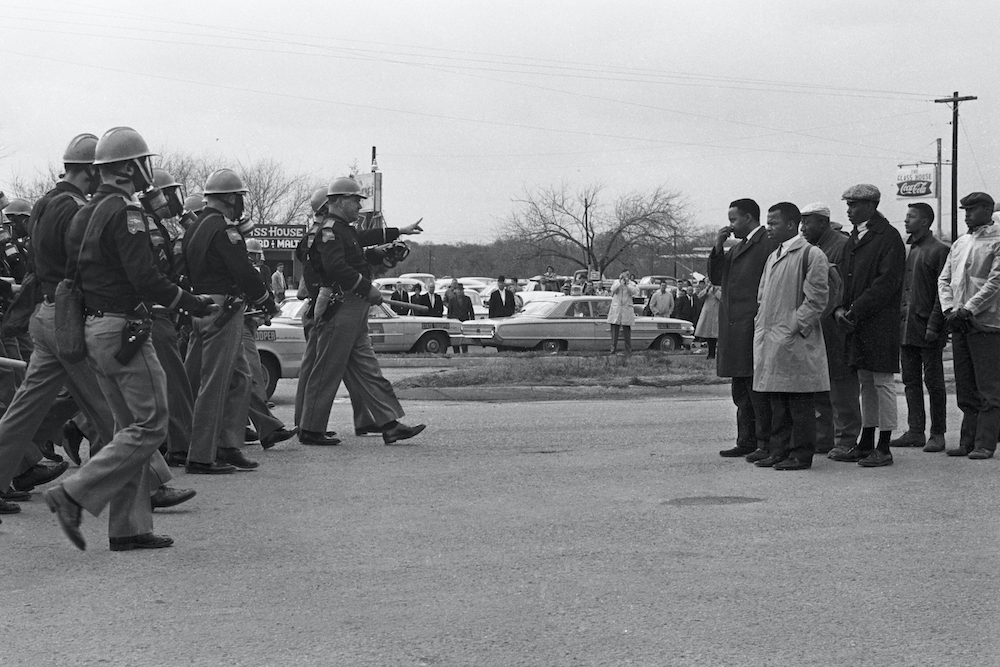

Police officers are seen confronting protesters on Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965, in Selma, Alabama, shown in a scene from "John Lewis: Good Trouble," a Magnolia Pictures release. (Courtesy of Magnolia Pictures/© Spider Martin)

Turning 92 this September, with his shock of white hair, resembling an Old Testament prophet, Lawson eulogized his mentee at Lewis' Atlanta funeral. Inspiring his students to desegregate Nashville's lunch counters in 1960, making it the first Southern city to do so, in the video, the professor urges his acolytes: "as creatively as possible seek to be loving and forgiving in any situation."

Non-violence, Lawson says, "is not a self-defense position. It is a militant position. How can I transform the environment in which I live?" For Lewis he "had to keep loving the people who denied me service."

Assaulted several times during the 1961 Freedom Rides, which attempted to desegregate inter-state busing, his skull fractured famously on Selma's Edmund Pettus Bridge on "Bloody Sunday" March 7, 1965, and arrested 45 times for civil disobedience, Lewis, nonetheless, in his final missive, said, "I still believe non-violence is the most excellent way."

That commitment precipitated his demise as SNCC chairman in 1966. Leading the organization since 1963, Lewis couldn't abide incoming chairman Stokely Carmichael's (Kwame Ture) more militant embrace of Black Power. "Whatever we do we must do in an orderly, peaceful, non-violent fashion. I never chanted 'Black Power.' We all have power," he says.

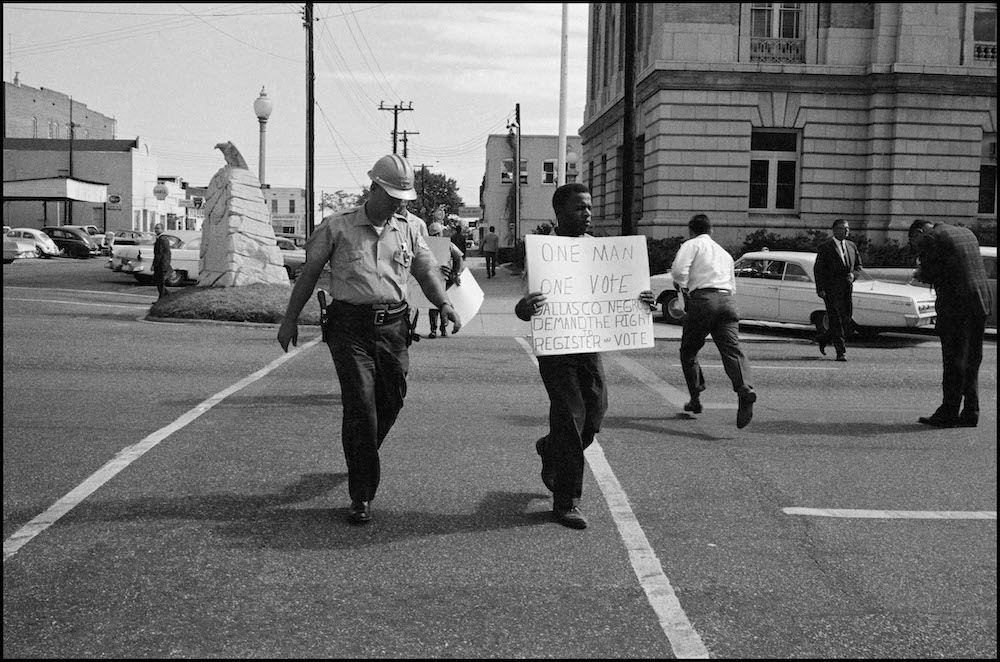

Voting rights, as "Good Trouble" well demonstrates, was the cause of the congressman's life. Having spilled his blood to secure the passage of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) Aug. 6, 1965, Lewis was proud to work with Wisconsin Republican Congressman James Sensenbrenner to win the VRA re-authorization, which President George W. Bush signed July 27, 2006.

But the U.S. Supreme Court's June 25, 2013, decision in Shelby County v. Holder was, the congressman says, "a dagger in the heart of the VRA." An affluent, predominantly white county south of key civil rights frontline, Birmingham, Shelby County challenged the constitutionality of VRA provisions, which required states to pre-clear changes in their voting laws with the U.S. Justice Department.

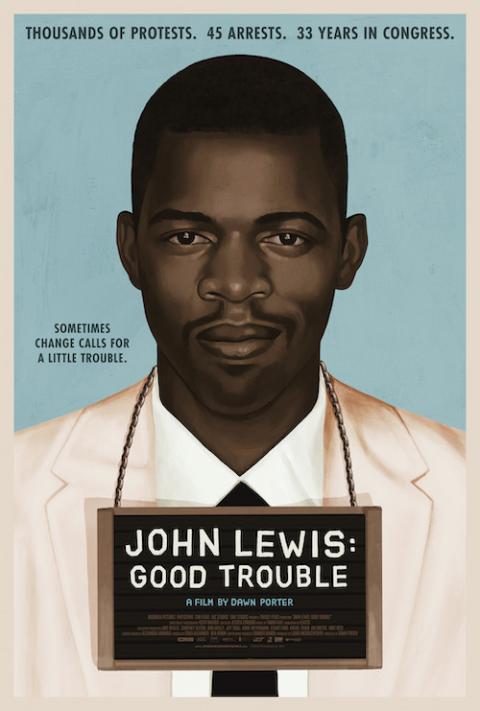

Theatrical one-sheet for "John Lewis: Good Trouble" (Courtesy of Magnolia Pictures)

In a 5-4 decision written by chief justice John Roberts, the court declared racial discrimination was no longer rampant and coverage formulas determining which states were subject to pre-clearance hadn't been updated since 1975. To which Lewis says, "There are those who say history cannot repeat itself, but I say come and walk in my shoes."

In this "disastrous" ruling's wake, former U.S. attorney general, the eponymous Eric Holder says, 27 states moved to enact unreasonable voter ID laws, purge voter rolls, and close or move polling places without warning.

Recently renamed the John Lewis Voting Rights Act, the first legislation the new Democratic house majority enacted in the 116th Congress, seeks to restore the VRA. But like so much good legislation, it collects dust on Senate Majority Leader Kentuckian Republican Mitch McConnell's desk.

The film's discussions about non-violence and voting rights edify, but "Good Trouble" suffers from numerous omissions. Only two minutes are devoted to Lewis' 44-year marriage to his wife Lillian Miles. We certainly want to know more about her influence upon him, how she supported his work, and why the marriage lasted. Their son John Miles makes a cameo, but we also wish to hear more from him.

"Good Trouble" touches upon but doesn't go into enough detail about the controversy surrounding the draft of Lewis' Aug. 28, 1963, March on Washington speech, which some felt was intemperate. Once considered the "most dangerous Negro in America," famed labor leader A. Phillip Randolph, who first conceived of the march in 1941, pleaded with the 23-year-old not to blow what he worked so long to accomplish.

Catholic viewers would be interested to know Washington Archbishop Patrick "Paddy" O'Boyle, who famously de-segregated local Catholic schools in 1948 six years before Brown v. Board of Education and gave the march's invocation, threatened to pull out if Lewis didn't temper his militant language. For instance, a passage about citizens in Danville, Virginia, living "in fear in a police state" raised alarms. Substituting "of a police state" for "in a police state," Lewis made a subtle change, which mollified his critics.

Another Catholic connection: Among the books Lewis carried across the Pettis Bridge in Selma was Thomas Merton's Seven Storey Mountain, the classic autobiographical spiritual work of the Trappist monk.

Despite its shortcomings, "Good Trouble" creates some evocative moments, which will stay with viewers. Recalling a scene from his long running PBS series "Finding Your Roots," Harvard historian Henry Louis Gates describes what happened when he showed the voting rights' advocate his great-great grandfather Tobias Carter's voter registration card from 1867.

"As soon as he was free and soon as it was law," Gates told Lewis, his ancestor registered. And the TV host observes Lewis was the next person in the family to register. Dabbing tears, Lewis, Gates recalls, says, "I guess it's part of my DNA."

John Lewis carries a sign for voting rights while being followed by a police officer in a scene from "John Lewis: Good Trouble." (Courtesy of Magnolia Pictures/Magnum Photos/© Danny Lyon)

[Chris Byrd frequently reviews books, films and TV shows for Catholic publications.]