Mary McGahey Dwan died Feb. 1. She was 81 years old. She died suddenly.

Caitlin Hendel, NCR publisher, and I had lunch with her at her house that day. I left her about 3:30 p.m. She probably died sometime during the night, probably from a heart attack. Not a bad way to go, all in all.

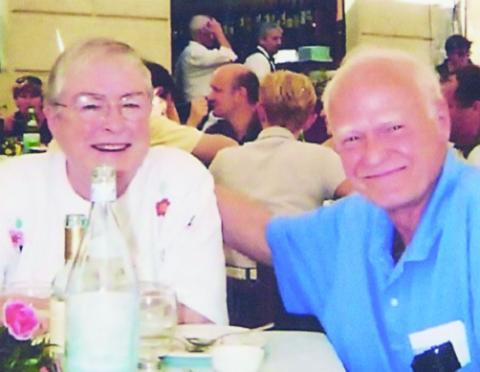

Mary and Ralph Dwan (Provided photo)

Mary's death deserves to be noticed, not just by her friends and family, but by the readers of NCR. Mary, together with her deceased husband, Ralph, had financially supported the NCR Washington Bureau for many years, and is supporting NCR's Vatican coverage. NCR was just one of many groups and individuals to benefit from her generosity.

Ralph and Mary were much more than philanthropists. They were role models of Catholic holiness. They lived simply and devoted their considerable resources to works of charity. They began every day with Mass and the Eucharist. They prayed the Liturgy of the Hours together in their home, sitting on opposite sides of their living room like a convent chapel. Their days were taken up with charity for the poor, the preservation of the environment, the education of young people and the development of the church.

Mary was a holy woman who had absolutely no time for saccharine piety. She didn't like stories of saints who flew. She was much more impressed by people who lived lives of holiness in ordinary circumstances.

She was a practical woman but she was filled with high ideals.

She was a tough-minded woman who didn't complain about her own problems, but was a soft touch for everyone else's. She always asked about your story, but she never really told her own.

Over her lifetime, she gave away millions of dollars, but hardly ever bought anything for herself. Her bedroom was bare, like a monk's cell. There were no carpets, no jewelry and no fancy clothes.

Mary's life was devoted to big thoughts and a universal perspective. She accepted modern science, but still lived in a world informed by faith. She loved her country and community, but her concern did not stop at America's borders. She thought globally, but acted locally.

Mary loved people and all their stories. She saw God in everyone, no matter their race, gender, age, language, culture, social status, sexual orientation or educational background.

Mary was a traditional Catholic who was also a persistent liberal. She never gave up on the reform and renewal of the church. One time after the election of Pope Francis, she called me on the phone and said, "I woke up feeling happy today, because Francis is pope."

Mary was part of the Vatican II generation. She read Commonweal, America, The Tablet and National Catholic Reporter. She had no time for people who wanted to turn the clock back on the reforms of the council. She favored:

- Women's ordination to the diaconate and priesthood;

- Optional celibacy for priests;

- Ecumenical dialogue with other religions;

- Racial justice;

- Building bridges to the gay community;

- The right of gay people to marry and adopt;

- An end to capital punishment;

- A church focused on building peace around the world;

- The view that being pro-life did not stop with abortion;

- The view that health care was a right, not a privilege.

While many members of the hierarchy did not share her views, she took comfort in the fact that most ordinary Catholics agreed with her.

Mary's life is a profile of American Catholic life in the last half century. She was born in Wisconsin and raised in Toledo, Ohio. Her mother was a homemaker; her father worked for the Ann Arbor Railroad.

The family was Midwestern, unafraid of hard work or bad weather. They asked a lot of themselves and presumed the best in everyone else. If someone was poor, Mary figured they had just had some bad luck. She gave the benefit of the doubt.

Like many Catholic school girls in the 1940s and 1950s, she saw no limit to women's ambition or achievement. Mary thought that women should able to be and do whatever their God gave them the talent to be or do.

After Catholic grade school and high school in Toledo, she went to St. Mary's College in the "Vatican" of the Midwest — Notre Dame, Indiana. After graduation in 1958, she entered the Sisters of the Holy Cross.

This was not surprising. It is worth recalling that in the 1950s, the only female college presidents, hospital CEOs, heads of charitable organizations, professors, or high school principals were nuns. Of course, Mary would become a nun.

Immediately after she took her vows in 1960, she went on to get two master's degrees, one in theology from the University of Notre Dame in 1962, and another in education from Boston College in 1964.

In 1964, Mary was assigned to teach in Washington at St. Peter School on Capitol Hill. She taught seventh and eighth grades there for five turbulent years in the midst of the Second Vatican Council and the civil rights movement.

During the late 1960s, she started taking her class to visit a community center in Southeast Washington run by a handsome and idealistic young priest, Ralph Dwan. Like her, he was also from a Midwestern Catholic family and, like her, he was filled with idealism. They fell in love.

They met helping a homeless woman who had come into Ralph's community center. The woman needed to go to the hospital, so Ralph and Mary took her to the emergency room at D.C. General Hospital. They spent much of the night in the waiting room. While they waited, they shared a cigarette, scandalous in the 1960s.

In 1969, Ralph left the priesthood in the controversy over contraception and Pope Paul VI's encyclical Humanae Vitae. Ralph dissented from Paul's absolute ban on artificial contraception. Cardinal Patrick O'Boyle, then archbishop of Washington, would have none of Ralph's dissent and forced him and nearly 100 other men out of the priesthood.

About that time, the Sisters of the Holy Cross sent Mary to the University of Michigan to get her doctorate. Her order was preparing her to be president of St. Mary's College.

Ralph, a graduate of University of Michigan Law School, made frequent trips to Ann Arbor, "to visit his professors," said Mary.

Advertisement

I once said to her, "Oh Mary, Ralph was not visiting his professors. He was there to see you." She smiled.

Mary left the sisters in the fall of 1970 and she married Ralph Dec. 30, 1970. They got married in an Episcopal church because Ralph's dispensation from his vow of celibacy had not come through. They wanted to get married before the end of the year for tax reasons. O'Boyle knew that. He delayed Ralph's dispensation in a little bit of pique. Mary and Ralph never held that against the cardinal. From them, O'Boyle had a lifetime pass because he had integrated the Catholic schools in Washington and they loved him for that.

Just a few days after the New Year, in 1971, Ralph's dispensation came through. Ralph and Mary had a second wedding in the parlor of St. Joseph's rectory on Capitol Hill.

Mary and Ralph settled on Capitol Hill. Ralph opened his legal practice in a second floor walkup. He did mostly free legal work. His clients were cab drivers and waitresses, and other ordinary people.

Ralph was one of several heirs to a substantial fortune. His grandfather had been one of the five founders of 3M — the Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company — the makers of Scotch Tape and Post-it Notes. Ralph's family viewed their wealth as a trust from God.

At first, Ralph and Mary lived in a tiny row house, just 16 feet wide. They bought two tiny row houses next door to each other, one to live in and the other for their books. They were great readers.

They tried to adopt children, but Catholic Charities turned them down. Ralph was considered too old at age 36. So they decided to help as many children as they could and spent their time and money doing good for other people's children. Mary would often anonymously pay young people's college or graduate school tuition.

Sometimes Ralph and Mary did extravagant acts of kindness. Once they tipped a waitress many thousands of dollars. Mary often paid anonymously for people to go on spiritual pilgrimages to the Holy Land and other shrines.

They had two parishes. On weekdays, they went to St. Joseph's on Capitol Hill and on weekends to St. John Vianney in southern Maryland. That is where I met them.

They both had a great love for the serenity and beauty of the woods and waters of the Chesapeake Bay region. They were among the founding members of a land trust to preserve the natural surroundings for future generations. At Mary's death, the American Chestnut Land Trust had purchased or preserved about 3,500 acres in the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

Miles of trails were created that future generations will enjoy because of Ralph and Mary. They thought globally, but acted locally.

In our parish in southern Maryland, Ralph and Mary were involved in two things: the Rite of Christian Initiation for Adults and processing annulments. For more than 17 years, they did all the work for annulments in our parish because they recalled how important the dispensation had been in their own lives.

They visited the parish every Friday afternoon. Ralph did the interviews. Mary waited in the outer office. Together, they wrote of up the annulment files. Their submissions were always perfect. Our little parish became known as the "Reno" of the church, the place to go if you needed an annulment.

In the 1990s, Mary got involved in a new project, the Lay Centre in Rome, to help educate laypeople studying theology. Co-founder Donna Orsuto had created a residence, chiefly for women studying theology. I suggested to Mary that she might want to get involved and asked her if she would buy a computer for the center. Mary smiled. "I think we could do that much," she said.

Today, the Lay Centre is firmly established in Rome largely because of Ralph and Mary Dwan.

Mary loved Catholic Charities and gave generously to our local Catholic Charities agency every year. But when it stopped doing adoptions because it would not handle adoptions for gay couples, Mary cut back her annual contribution from $50,000 to $10,000 per year. She gave the rest to food pantries. She thought gay couples should be able to adopt.

When Ralph died in 2011, Mary was devastated. I thought she would decline rapidly but she didn't. She took on new projects.

On a personal level, I turned more and more to Mary as a sort of spiritual director. Her advice was always practical and always charitable.

She died as she lived, very simply. We found her in her bed. No pillow under her head, only one light, threadbare blanket over her. Just like Mary, no fuss, no trouble, no big deal. She simply fell asleep in this world and woke up to eternal life.

Mary was a holy woman but not pious. She saw life straight on. She accepted people without judgment. She was the best that our Catholic Church can produce.

If she is not in heaven, then nobody is, and if she is not in heaven, then I don't want to go.

Rest in peace, Mary. Our world and our church are much better because of you.

[Fr. Peter Daly is a retired priest of the Washington Archdiocese and a lawyer. After 31 years of parish service, he now works with Catholic Charities.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time Fr. Peter Daly's column, "Parish Diary," is posted to NCRonline.org. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.