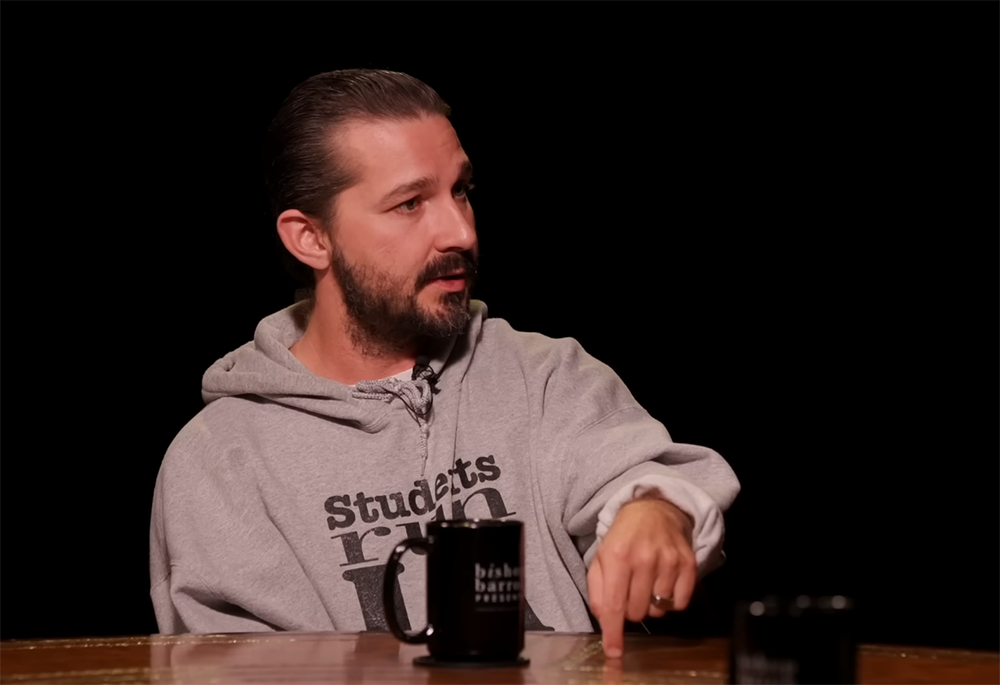

Actor Shia LaBeouf speaks with Bishop Robert Barron of the Diocese of Winona-Rochester, Minnesota, during "Bishop Barron Presents." (YouTube screenshot/Bishop Robert Barron)

The hour-and-a-half conversation between actor Shia LaBeouf and Bishop Robert Barron of the Diocese of Winona-Rochester, Minnesota, lasts only seven minutes before the tension surrounding the Latin Mass comes up.

While the motive of the interview is primarily to discuss LaBeouf's portrayal of the titular saint in the forthcoming feature film "Padre Pio", the major revelation of the dialogue is LaBeouf's conversion to Catholicism, which is first brought to light through the discussion of, essentially, the role of the secret within the sacred as it pertains to differences between the Catholic liturgy's ordinary and extraordinary forms.

LaBeouf's own words praising the Latin Mass are, for lack of understanding Latin: "I can't argue the word, because I don't know what the word means, so I'm just left with this feeling." Barron himself brings up that a secondary purpose of incense at Mass is that it obscures the action in the sanctuary.

I understand the modern human impulse toward the obfuscated to achieve spiritual enrichment. We are constantly on display, thanks to the surveillance and pressures to perform by social media. We have access to a wealth of information at any second thanks to the internet in our pockets, on our phones. There is very little we couldn't know if we wanted to. Of course, we then find the unknowable, the secret, interesting and enriching.

Actor Shia LaBeouf gestures during an interview with Bishop Robert Barron. (YouTube screenshot/Bishop Robert Barron)

All the same, the digital expanse of public knowledge and performance has brought to light the dark underbelly of countless institutions, from Hollywood to the church. This is the core of the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements. Such were the things being obfuscated: bigotry, sexism, racism.

"You can't argue the words, so you're left with a feeling" is itself a concept that requires accurate assumptions, the absence of which can lead to cultural appropriation and manipulation. It calls to mind conversations around consent. Words are important. If the option exists for a willing participant to fully understand what is being said around and to them, that should be the preference. Now, if a performance is situated in a cultural context that is best reflected in the culture's native language, then by all means, use the native language! Is Latin the global church's native language? Is Catholicism a culture?

LaBeouf also says, before his conversion, he did not initially feel compelled to have a relationship with Jesus because he only knew the "soft, fragile, all-loving, all-listening but no ferocity … meek" Jesus (Barron immediately offers the word "feminized"), and it was only when LaBeouf encountered what he considered to be "masculine" — "cape, dipped in blood, sword" — that Jesus felt "appealing."

We should be concerned about anyone who finds the Gospel most compelling in its violence or who is put off by the femininity of Jesus. If we are to understand Jesus as the savior of all, we must embrace his full divinity that has no gender, and we must confidently identify the goodness of both the masculine and feminine in the incarnation.

Throughout the interview, LaBeouf cites a number of tropes and returns to them often: cowboys, cavemen and gangsters. He repeatedly expresses gratitude for the men who accompanied him and "masculinized" his journey, "the hero's journey."

Advertisement

LaBeouf also discloses the heart of this pull to the masculine: He is drawn to those who treat him in a fatherly or grandfatherly way, and he is lonesome for friends. He finds all of these things in the Catholic world.

As a person also in relationship with the Capuchin Franciscans, I also find it unsurprising that their community is balm to his wounds. One member of the very same Capuchin community who met and accompanied LaBeouf during the production of the film is presiding over my wedding in just a few weeks. I have dined at the same table as LaBeouf — albeit at different times — and my non-Catholic fiancé and I were both warmly welcomed and invited to share our very different experiences of faith. LaBeouf says it himself: He was looking for "safety," and found it at the Capuchin table.

At the time of his initial engagement with Catholicism, LaBeouf's mother wasn't speaking to him and his career was flatlining. LaBeouf shares about experiencing suicidal ideation and total lack of hope. Once he embraces the Gospel, he feels God calling him to let go of his egotistical striving for power. He finds the safety he was looking for in "non-transactional" relationships where he isn't expected to do anything besides contemplate how best to use his gifts for others. It is a beautiful narrative of acceptance.

And yet still, the concerns about the attractiveness of Catholic violence and secrecy cannot be downplayed, as they directly relate to LaBeouf's troubled past. LaBeouf minimally addresses the accusations made against him in the last few years, referring to them only as "the news." Barron never asks.

Bishop Robert Barron speaks with Shia LaBeouf during "Bishop Barron Presents." (YouTube screenshot/Bishop Robert Barron)

Quietly underscoring the narrative arc of LaBeouf's conversion story is the opportunity for penance in the sacrament of reconciliation. Much online discourse around the criticism of LaBeouf's conversion story and lack of direct accountability for his past violence is rooted in the assertion that whether or not a person sinned is between them and God. Here we have returned to the dangers of secrecy within the sacred, the concerns about the seal of confession when violence of any kind is involved, the questions about authentic accountability.

At the tail end of the interview, it is Padre Pio's "toughness" within the confessional that plays a crucial role in LaBeouf's connecting with the character once filming of the movie begins. LaBeouf offhandedly shares a story about Pio sending away a woman whose ankles were showing, a story that seems to have been included in the film. (Be advised, the clip contains adult language.) Against the backdrop of LaBeouf's own transgressions, this story is revealing. How might the woman have felt?

The experiences of those in the orbit of aggressive men are so often eclipsed by "the hero's journey" of conversion and redemption. In his piece on the LaBeouf interview for the Black Catholic Messenger, Gunnar B. Gundersen upends this narrative by centering and amplifying the faith of LaBeouf's ex-girlfriend, FKA twigs, and her place in this story. Gundersen holds Barron accountable for this erasure:

Shia LaBeouf did not decide on his own to give himself this platform to share his imperfect faith journey. Bishop Barron … decided to amplify LaBeouf's voice and provide him a place of prominence in FKA twigs' Church — a home that is supposed to be for all, including Black women.

As Barron and LaBeouf chuckle about Pio wrestling with the devil and coming away with broken bones and a bloody nose, the backdrop of the entire conversation is still, clearly, masculine aggression. A physical devil need not be present for destructive men to enact their rage on their surroundings. Could we fairly interpret "wrestling with the devil" as wrestling with one's own violent tendencies?

The parallels draw themselves between the performed and the performer. The lack of clarity that swirls around Hollywood rumors like a cloud of incense so too swirls around the inner lives of the saints. On the one hand, this interview is an impressive story about the transformation made possible by engaging with the saints and the dire need of all people for non-transactional, inclusive community. This interview is also a powerful man accused of mistreating people sitting across from another powerful man accused of mistreating people situated within a system that enables powerful men to mistreat people.

Barron says, at the conclusion of the interview, that "the Bible is much more interesting than my experience" and encourages us to envision our own lives swept up into the story of the Bible. Even with historical context, we cannot insert ourselves into historical stories and not have our lived experience intrinsically shape our imagining.

This is, perhaps, the crux of LaBeouf's time as Padre Pio. We can have as much historical context as possible about Pio, and it is still Shia LaBeouf — with all his wrongs — making sense of a story around his own experience. Having not yet seen the movie, I look forward to seeing how the parallels play out.

Having no means or desire to ever become privy to the inner machinations of another human person's relationship to Christ, I have no way of truly knowing Shia LaBeouf's process of reconciliation. Far greater than the opportunities for conversion this may inspire are the opportunities to pray from a place of hope for the earnestness of interior conversion and for trustworthy outward displays of changed behavior. Worrying about LaBeouf's soul any further is probably, as in Padre Pio's own overcirculated quote, "useless."