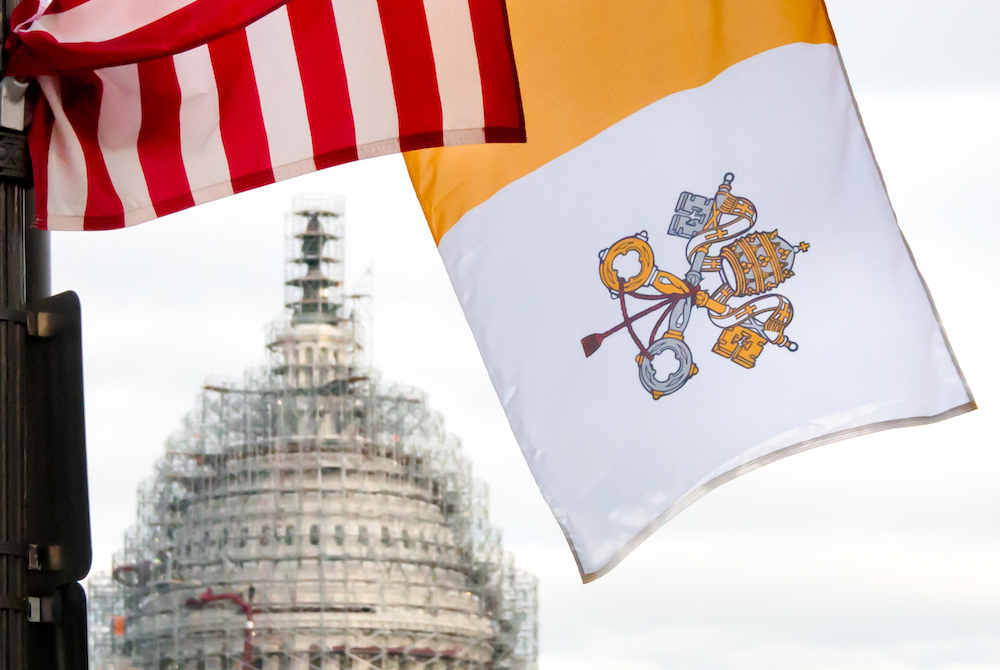

Vatican flags along Pennsylvania Avenue for Pope Francis's visit (AP/Flickr/Victoria Pickering)

Joe Biden will soon be the first Catholic president to nominate an ambassador to the Holy See, something that in earlier days would have been anathema to American Protestants who feared the papacy's political and religious power. They believed Catholics would impose their religion on the country if they ever attained power. In 1867, Congress even passed a law forbidding spending government money on an embassy in Rome. This law remained on the books until 1984.

That the nomination this time will be noncontroversial shows how anti-Catholicism has declined in the United States and how more and more people recognize the value of having an ambassador at the Vatican.

Despite their Protestant fears, the founding fathers were very pragmatic in dealing with the papacy. After the revolution, American merchants wanted access to papal ports since the Vatican controlled about a third of Italy at the time. Money trumped sectarian fear, so in 1797 the U.S. had a consul in Rome to deal with commercial affairs. This only ended in 1867, when mounting anti-Catholicism led Congress to cut off diplomatic relations.

Once the papacy lost most of its territory in 1870, the commercial value of diplomatic relations disappeared. But in the eyes of the Vatican, the Holy See as head of the Catholic Church is an international actor with diplomatic status recognized under international law even if it did not have any territory, and it insists diplomatic relations are with the Holy See, not the Vatican City State. For its part, the U.S. State Department prefers to speak of diplomatic relations with the Holy See as head of the Vatican City State, not head of the Catholic Church.

Pragmatism won again during World War II, when the U.S. saw the intelligence value of having a diplomat behind enemy lines in Rome. President Franklin Roosevelt publicly referred to Myron Taylor as his "personal representative," even though he secretly (and perhaps illegally) appointed him a U.S. consul so he would have diplomatic status and thus be protected under international law.

After the war, President Harry Truman tried to reestablish diplomatic relations with the Holy See with the appointment of former Gen. Mark W. Clark as ambassador, but he failed because of opposition in the U.S. Senate. Presidents Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan followed Roosevelt's example and appointed nonsalaried personal representatives.

Advertisement

Carter, a Baptist, was the first president to appoint a Catholic to this position. Since then, all have been Catholics. Though, the Vatican does not care whether the representative is a Catholic or not. It prefers someone with good connections to the State Department and the White House who can be a good channel of communications.

For example, no one in the State Department or White House took seriously Ambassador Raymond Flynn's warnings that the Vatican and the U.S. were heading toward a disastrous confrontation at the 1994 U.N. conference on population and development. On the other hand, some ambassadors were so well connected their phone calls went directly to the president or the secretary of state.

As a Catholic, Joe Biden might recognize the value of again appointing a non-Catholic to this post, perhaps someone like Rabbi David Saperstein or evangelical social activist Jim Wallis. This would avoid the debate over whether the appointee is a "good" Catholic. It would also avoid a Catholic ambassador's temptation to get involved in internal church affairs.

It was not until 1984 that Congress authorized diplomatic relations with the Holy See and Reagan appointed William A. Wilson as the first ambassador. With his own money, Wilson had hired a lobby firm to push Congress into repealing the 1867 law.

Opposition to the establishment of diplomatic relations in 1984 came from Jewish and Protestant groups as well as liberal Catholics who objected on constitutional grounds. The constitutional issue was settled by the courts, which recognized the president's right to establish diplomatic relations with any international entity.

Liberal Catholics also feared the Reagan ambassador would attempt to influence the appointment of Catholic bishops in the United States, but American officials have rarely attempted to influence episcopal appointments.

President Joe Biden departs after attending Mass at St. Joseph on the Brandywine Catholic Church as snow falls, Sunday, Feb. 7, 2021, in Wilmington, Delaware. President Biden is tasked with selecting a new ambassador to the Holy See to recommend to the Senate for confirmation. (AP/Patrick Semansky)

After the American Revolution, even before there was a U.S. Constitution, the Vatican recognized the need to establish in the new country a diocese independent of Europe. The papal nuncio in Paris approached Benjamin Franklin and asked how the church should proceed. He wrote the Continental Congress for instructions and they told him to have nothing to do with it. This was the first time the papacy was told by a government that it did not want anything to do with the appointment of bishops.

While that is the official story, we know from Franklin's diary that he went on to praise the Rev. John Carroll as a wonderful priest. Carroll had nursed Franklin when he was sick on their trip back to Philadelphia from Canada, where they failed to persuade French Canadians to join the revolution. The Vatican took the hint. Luckily, Carroll was also the choice of the local priests, so everything worked out.

Roosevelt, concerned about some Catholic bishops' opposition to the New Deal, tried but failed to get one of his favorite bishops promoted. On the other hand, John O'Connor, a conservative bishop and former head of the military vicariate, was promoted to New York a few days after diplomatic relations were established. The Vatican knew how to say "Thank you" to the president who established diplomatic relations with it.

But for the U.S. State Department, pragmatism is the key to U.S. diplomatic relations with the Holy See. Diplomats have always seen Rome as an excellent listening post since the Vatican gets information from bishops and religious orders all over the world. It frequently has better sources on the ground than the CIA.

The State Department also recognizes that papal statements have worldwide impact, so it wants to be present to influence the content and timing of these statements.

Every administration has areas of agreement and disagreement with the Vatican. The Vatican is looking forward to working with the new administration and its ambassador on climate change, the Middle East, migrants and refugees and world poverty. Both sides will agree to disagree on issues of abortion, birth control and gender, but these issues will not stop them from working together.

The Vatican will also support the Biden multilateral approach to foreign policy as opposed to the Trump administration's unilateralism. But first, the president must nominate and get through the Senate a new ambassador, something that would have been impossible for much of American history.