Westchester County, New York (Karen Nanko)

Why do Latin@́s show up for Good Friday in larger numbers than Easter Sunday? Around this season, this question makes the rounds in pastoral circles. Viernes Santo, or Holy Friday in Spanish, is the only day in the liturgical calendar when Mass is not celebrated at all. The liturgies and ritual actions of the day — whether in the church, the streets or homes — keep the focus on the suffering and crucifixion of Jesus. The brutality, narrated in the Passion of John's Gospel or experienced in the motion of a Via Crucis, discourage any romanticization of this death. The corpus, bloodied, beaten and broken, is venerated, defying attempts to sanitize suffering.

There is something about Viernes Santo that sticks to memory. I can still recall our parents making us sit still starting at noon on that day. From my childhood recollections of my parish church, I can still feel the sadness emanating from the statues of the saints with their heads veiled in purple, an action, I interpreted at the time, as shielding their eyes and ears from the horrors to come. Even to a young kid, the rhythm of sit, stand, kneel, traditioned us to understand that something was profoundly different about this day.

In Latin@́ God-talk, Good Friday and the popular practices that mark la lucha de Jesús and his mother remain vibrant sources of theologizing. In Caminemos con Jésus, theologian Roberto Goizueta observes, "The Easter Vigil cannot compare either in the time devoted to the celebration, the sheer number of participants, or the extant or intensity of their participation" (32). What sets Good Friday apart is the struggle. The incarnation meets lived reality in a way that conveys God gets it! God understands the struggles of those who are oppressed, of the innocent who suffer injustice, of a mother who mourns the loss of a child, of profound abandonment and isolation, of death. God gets it, because through Jesus, God lives it!

There is something visceral about Viernes Santo that does an end run around our desire to rationalize and strikes, instead, at our hearts. The affective dimension of popular practices, with their appeals to the senses, play out in motion, not only within our churches, but through our streets. El Via Crucis of San Fernando Cathedral in San Antonio, through Pilsen in Chicago, over the Brooklyn Bridge in New York, at the border en El Paso are contextualized within the barrios and landscapes they traverse.

Advertisement

When Jesus falls for the first time, it is before the home where a family lost their lives in a fire. When the women of Jerusalem weep, it is before the immigration courts and detention centers. When Simon takes up the cross, it is on the corner where a youth center offers shelter or a kitchen serves meals. Through the streets, these local expressions of the Way of the Cross move with the crowds, re-inscribing the body of Christ as really present in the neighborhood.

The embrace of accompaniment as mutual is key to understanding Latin@́ responses to Good Friday. On this day, those who have been accompanied, through their daily struggles in life, by Jesus, by his mother María, now, in turn, accompany them in their darkest hour. In his vulnerability, Jesus mirrors our own vulnerability, as well as our shared need for solidarity in and through suffering. In his book, Mozarabs, Hispanics, and the Cross, theologian Raúl Gómez-Ruiz demonstrates how Hispanic spiritualities, through the ritualized actions of Good Friday, "stress the passion as an active, communal undertaking over against suffering passively endured by a solitary individual" (179). The privileging of relationality leads to the conviction that Jesus is not the only one who suffers. So does his mother, and her grieving also calls for acompañamiento. Through such popular practices as the Pésame, consolation and respects are offered to the sorrowful mother, a recognition of the communal impact of death and loss.

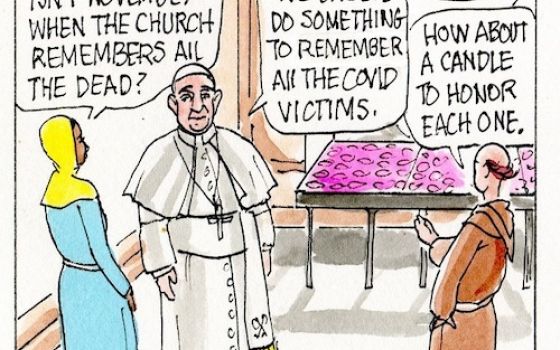

As we prepare for and participate in a virtual Triduum, we may liturgically be moving from Good Friday to Easter, but amid a pandemic the reality is more like Good Friday meets "Groundhog Day," a colloquialism referencing the 1993 film where the main character, trapped in a time loop, relives the same day over and over again. We are facing rolling weeks of peaks and plateaus. As one city or region or country exhales, another holds its collective breath. An endless stream of Good Fridays appears to loom on the horizon. How do we reclaim agency in the face of waves of suffering, gripped by fear, immobilized by uncertainty, shrouded in tears for our sick and dying loved ones? How do we shift to an understanding of isolation as "an active, communal undertaking" as opposed to a "suffering passively endured by a solitary individual"?

A street sign in Santa Monica, California, thanks essential workers April 6 during the coronavirus pandemic. (CNS/Reuters/Lucy Nicholson)

In this time of COVID-19, how do we live into Good Friday? How do we enact accompaniment in a time of distance? Paradoxically, most of us accompany now through our physical absence. We wipe the faces of the suffering by covering our own faces with masks — homemade perhaps — but not the ones that are in short supply and needed by first responders and health care workers.

Like Simon of Cyrene, we take risks as essential workers, by reporting to work. Some of us head to professions on the frontlines that always carried an element of risk, and others of us to jobs hidden in plain sight that only now are revealed as vital to the survival of our communities. Like the meeting of mother and son on the Way of the Cross, we are the surrogate touch in ICU, or the one that makes possible a last farewell via a cellphone or tablet. We are the weeping women of Jerusalem waiting for word, praying even harder, for those we love and those we do not even know. We are Joseph of Arimathea awaiting the bodies, providing temporary resting places until families can bury the dead they mourn. We are Jesus, those among us who are walking the way of the cross, afflicted by a virus that threatens our very lives and cuts us off from the human touch we most crave.

The many Via Crucis that spill into the streets make visible the suffering bodies of Christ in our own places. They function as resistance, reconfiguring space in ways that, as theologian Orlando Espín contends, reject a privatization of religion yet affirm the potential of our religious practices to denounce social sin and advocate for justice. There is no denying the hunger many experience in this time without Eucharist, in this Holy Week without palms.

If we believe, however, that we need a palm frond to enter deeply into our faith, then we have confused our faith with idolatry. If we hunger for the body of Christ yet expect that the bodies of Christ must pay with their health and lives to feed us, then our theology is malformed. If we confuse the false optimism of a return to "business as usual" with hope, then we will fail to address what Pope Francis has described as that aftermath that "has already begun to be revealed as tragic and painful, which is why we must be thinking about it now."

Homeless people practice social distancing in a parking lot in Las Vegas during the coronavirus pandemic March 30. (CNS/Reuters/Steve Marcus)

This aftermath demands a move from social distancing to social reckoning. We need to attend to those who risked all in service to others — when their post-traumatic stress begins. We must confront the cost of racism and xenophobia, prices paid disproportionately by African Americans, Asians and Latin@́s in security, health and lives. Socioeconomic inequities exacerbate chronic conditions that are heightened risk factors and limit available health care options. The shameful images from Las Vegas, a city of empty hotel rooms, lodging people who are homeless in parking spaces on the ground caught even the pope's attention. Shelter-at-home as a means of containment requires that we question our presuppositions, namely that home is safe and that all have homes. We must dismantle the layers of lies and complicity that obfuscated the scope and destruction of this pandemic and impaired our national ability to respond in timely and effective ways.

The tools that have made us visible and present to each other in this time of crisis invite us to reconsider our theological anthropologies, our ecclesiologies, our theologies of sacrament and incarnation, our means of pastoral care. Virtual presence is real! It makes education accessible, mobilizes advocacy, offers comfort, enables contact, expresses creativity. It engages us aesthetically and affectively and makes motion possible.

What happens when we configure our virtual presence as part of our Imago Dei? At best, on this Viernes Santo, we long for the moment to anoint the lost bodies of Christ and place them in the sepulcher. For now, we keep vigil. If, however, we fail to simultaneously prepare to address the pain and promise of the aftermath, then we will have missed Easter.

[Carmen M. Nanko-Fernández is professor of Hispanic theology and ministry, and director of the Hispanic Theology and Ministry Program at Catholic Theological Union (CTU) in Chicago. The author of Theologizing en Espanglish (Orbis), she is currently completing ¿El Santo?: Baseball and the Canonization of Roberto Clemente (Mercer University Press).]

Editor's note: We can email you every time a new Theology en la Plaza column is posted to NCRonline.org. Go here to sign up.

In memoriam of Msgr. Richard Guastella, pastor of The Church of St. Clare, Staten Island, New York