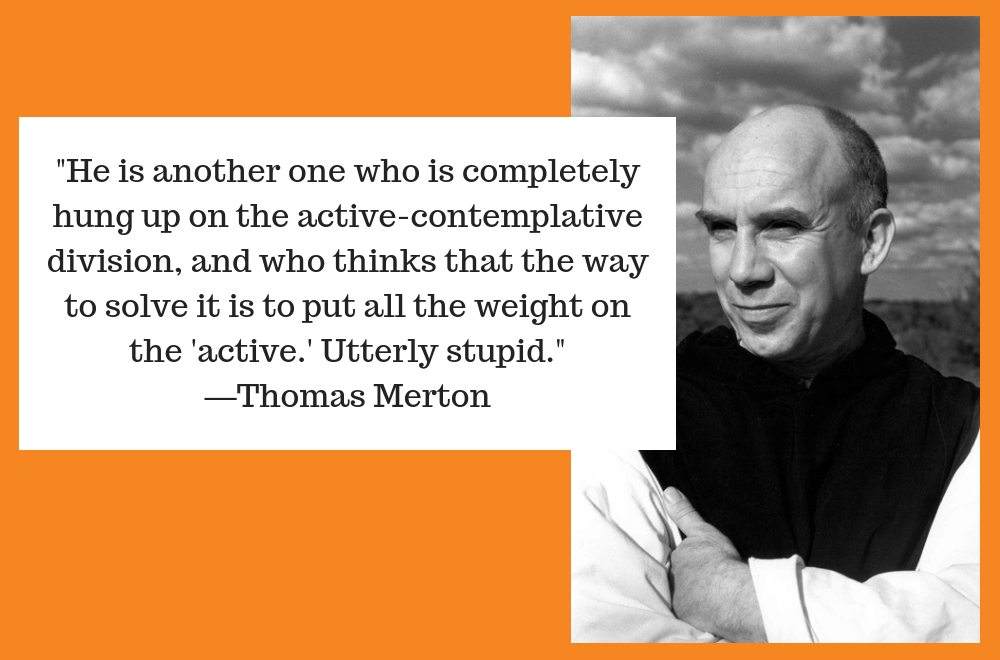

(NCR graphic/CNS photo/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University)

For many of us, Dec. 10 brings to mind, and sadly so, the 50th anniversary of Thomas Merton's death in at a monastic conference in Samutprakarn near Bangkok, Thailand. The day also marks his arrival in 1941 at the Trappist Monastery of Our Lady of Gethsemani in Nelson County, Kentucky, where for the next 27 years his surging literary output, including the 1948 autobiographical The Seven Storey Mountain that sold over 600,000 copies in the first year, and enduring spiritual classics like The Sign of Jonas: Bread in the Wilderness, would earn him fame and a global following as a spiritual master.

Whatever the rigors of the Trappist cloistered monastic life — priests and lay brothers rose at 2:15 a.m. to chant the Psalms and retired at 7 p.m. after compline, communication by sign language, no newspapers or other pagan distractions allowed — Merton, whose monastic life included the name Fr. Louis, really led two lives: one public, one personal. One driven to write for a massive audience, one who wrote typewritten letters stuffed into an envelope meant for a sole reader — and all the while writing seven volumes of a journal with the first entry on May 2, 1939, from New York City to the last on Dec. 8, 1968, in Thailand.

Merton's correspondence can be found in five thick volumes: The Hidden Ground of Love, The Road to Joy, The School of Charity, The Courage for Truth and Witness to Freedom.

"The work of writing," he explained soulfully on April 14, 1966, in his journal, "can be, for me, or very close to, the simple job of being: by creative reflection and awareness to help life itself live in me. … For to write is to love: it is to inquire and to praise, to confess and to appeal. This testimony of love remains necessary. Not to reassure that I am ('I write, therefore I am'), but simply to pay my debt to life, to the world, to other men. To speak out with an open heart and say what seems to me to have meaning."

I had a glimpse of Merton's "open heart" when I was researching an article for National Catholic Reporter that would run on Dec. 13, 1967, and be titled "Renewal Crisis Hits Trappists." I wrote asking for his thoughts on how he, his Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance and monasticism around the world were faring.

His lengthy four-part reply of Aug. 15, 1967, began: "Thanks for your letter. Sounds interesting. I gladly contribute what ideas I can, and here they are. Use what you like or can. Under separate cover I'll send a couple of recent papers that are not in print, and you can draw on them too if you like."

In prose that ranged from angry venting to cautious analysis about "a real ferment " in some monasteries, Merton held back little. "The term 'contemplative life,' " he believed, "is being used defensively as an excuse to keep monks in the monastery, to keep them out of contact with the problems and needs of the world, in short to keep them out of dialogue with the world. This is disastrous. Such a use of the term will bring complete discredit on the real value of contemplation. In a clumsy attempt to protect the monastic life, this negativism will only sterilize it and guarantee its demise."

Whether from his journaling or staying in touch by mail with sympathizers, it was well known that for years that Merton had an abbot, James Fox, who firmly held to the idea that cloistered Trappist monks willingly left the world behind forever, to be self-imprisoned in a commune of God's inmates. Unhappily, and seething, Merton wrote that he recently had a very interesting invitation to go to Japan and visit the chief Zen masters there, but permission to go was categorically refused. "My Superiors, in a state of almost catatonic shock, said: 'But this would be absolutely contrary to the contemplative life.' Comment on this is not necessary."

Five months after Merton wrote that, Fox retired, to be replaced by a new abbot who opened the monastery gates. So freed, Merton would soon be on his way to the East on a trip on that ended tragically.

Not long after NCR ran my piece, Merton let his dislike be known. "Don't take that article in the National Catholic Reporter too seriously by the way — if you saw it," he wrote to Sr. Elaine Bane on Dec. 21, 1967. "I mean the Colman McCarthy one. It is very slanted. I don't think half these people really knew what they are talking about. He is another one who is completely hung up on the active-contemplative division, and who thinks that the way to solve it is to put all the weight on the 'active.' Utterly stupid."

Two days later, and still irked, he wrote to Mother A: "Just a quick response. Colman McCarthy's article was extremely slanted, I thought, and I got slanted along with him by the way he quoted me. Actually, I agree with him to some extent about the failure of the contemplative orders up to a point. I don't think they are really contemplative. … But I don't think Colman McCarthy has a clue as to what it is all about. He knows that the official Trappist life isn't working, and that's correct. But he has no idea of what a real contemplative life might possibly be. And his notions of the apostolic life seem pretty sketchy too."

If Merton the monk initially left the world behind, the upheavals of the 1960s — the antiwar movement, civil rights — saw him bring the world to him. Visitors included Daniel Berrigan, Jacques Maritain, John Howard Griffin, Jim Forest and Joan Baez. Of the folksinger and pacifist, then 26, Merton wrote in his journal: "She is a very pure and honest girl, stays away from dope, everything, is rightly regarded as a sort of saint in the peace movement. Her purity of heart is impressive. A precious, authentic, totally human person. The thing I most sense, for some reason, is a kind of mixture of frailty and indestructibility in her."

Merton's deepest connections with secular life came in March 1966 following back surgery in a Louisville hospital when a student nurse was assigned to give him a bed bath. They fell in love, hard. Merton was 51, Margie Smith, with flowing black hair and gray eyes, was a student nurse decades younger. In no time, it was "clearer than ever that we are terribly in love, the kind of love that can virtually tear you apart."

Advertisement

For months into the spring and summer, after repeated secret phone calls, furtive lunches and dinners, sipping champagne in Louisville, Merton's journal entries and letters would lyrically run deep with his happiness: "We are moving slowly toward a complete physical ripening of love, a leisurely preparation of our whole being, like the maturing of apples in the sun." And: "There is something deep, deep down in us, darling, that tells us to let go completely. Not just the letting go when the dress drops to the floor and bodies press together with nothing in between, but the far more thrilling surrender when our very being surrenders itself to the nakedness of love and to a union where there no veil of illusion between us. Darling, I long for it madly. Do you see? Do you need me as well?"

Merton never married Margie Smith. She became the wife of a doctor and the mother of three.

While in Kentucky a while back, I took time to visit the Gethsemani monastery near Bardstown and Merton's grave site in the community cemetery. It was marked by a white cross and the name Fr. Louis.

Later in the gift shop I picked up some Trappist bread and jelly, in memory of my friend, Tom.

[Colman McCarthy, director of the Center for Teaching Peace in Washington, was a Trappist lay brother for five years at The Holy Spirit monastery, Conyers, Georgia.]