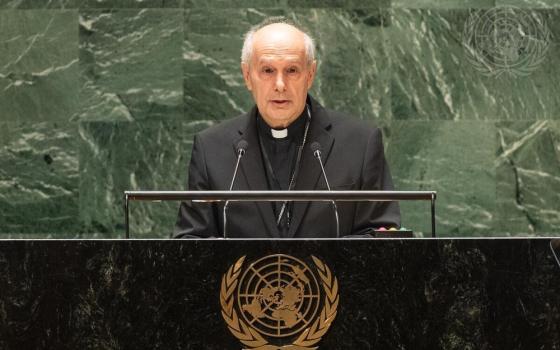

A screen capture from the recording of Franciscan Fr. Richard Rohr delivering his final remarks to and blessing for the 2022 cohort of the Living School in Albuquerque, New Mexico, July 30 (Courtesy of Cathleen Falsani)

The night before my mother's funeral in October 2019, I submitted my application to the Living School, a two-year program created by Franciscan Fr. Richard Rohr at his Center for Action and Contemplation in Albuquerque, New Mexico, to study Christian mysticism and other wisdom traditions, ancient and contemporary.

Three months later, I received word of my acceptance into the Living School's 2022 cohort, and six weeks after that, COVID-19 arrived, changing all our plans and the world as we knew it.

What an awful time to open a new chapter in my ongoing spiritual education, studying the "perennial tradition" of Christian contemplation and mysticism, I thought more than a few times over the last two years.

Yes, the timing was awful, and it also was perfect.

That last bit is part of the hard-won wisdom I was able to cultivate during my tenure as member at the Living School, which is, in the very best of ways, sort of like a finishing school for middle-aged mystics (and those aspiring to be). Learning nondualistic thinking — in this case that the timing could be awful and also perfect simultaneously, not just either-or — is one of the foundational principles of contemplative spirituality.

Only a few times in my half-century of life have I been blessed with the awareness of something coming full circle, to see and understand the spiritual growth that has taken me from there to here.

A cradle Catholic whose parents left the church for the Wild West of evangelical Protestantism not long after I'd made my first Communion, I had spent 15 of my 20 years of formal education in faith-based institutions, including private Christian prep school, an evangelical Christian college and the United Methodist seminary where I earned a master's degree in theological studies.

Add to that the 20 or so years as a journalist covering religion for mainstream media, during which I essentially went to church for a living, my religious education was robust long before I'd heard of Rohr or his school. But as I approached my 50s — entering what Rohr calls the "second half of life" — it also began to feel incomplete.

I yearned for something deeper that would connect my faith to a sustainable contemplative practice and with a wisdom tradition that is both ancient and dynamic. I also sought a new clarity of vocational and personal purpose as I entered what the writer Annie Lamott calls the "third-third" of life. I want to be useful, a good steward of my gifts and experiences, in the "called and gifted for the Third Millennium" sense of things.

It was around this time two things happened: Someone pressed a copy of Rohr's Falling Upward: A Spirituality for the Two Halves of Life into my hands and then an editor at Religion News Service, for which I occasionally write, asked me to travel to Albuquerque in early 2019 to interview Rohr for a long profile in advance of the release of what he expected to be his final "big" book, The Universal Christ. Between Falling Upward and my conversation with the Franciscan friar himself, I experienced an almost ineffable draw toward both the Living School and the Catholic spirituality of my childhood, something Rohr describes as feeling spiritually "homesick."

Advertisement

"We are both sent and drawn by the same Force, which is precisely what Christians mean when they say the Cosmic Christ is both alpha and omega," Rohr writes in Falling Upward. "There is an inherent and desirous dissatisfaction that both sends and draws us forward, and it comes from our original and radical union with God. What appears to be past, and future is in fact the same home, the same call, and the same God."

Our paths are never a straight line, they are spirals, Rohr says. Mine has certainly been that. Taken away from the Roman Catholicism of my Italian and Irish ancestors when I was in grade school, my family of origin landed, of all places, among the Southern Baptists (in southern Connecticut), where I learned a lot about grace and ice cream socials. That led to a long sojourn among American evangelicals (an extremely mixed bag), before I sauntered toward Canterbury and the Episcopal Church with its smells, bells and liturgy in my early 20s.

Since then, I have, to borrow a phrase from an Irish friend, been "as comfortable and uncomfortable" inside a Catholic cathedral as in any other church, without any set spiritual home. Always spiritually oriented with the things of faith central to my life, I remain a woman without a church.

Writer Cathleen Falsani and Franciscan Fr. Richard Rohr during the weeklong symposium in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in late July (Courtesy of Cathleen Falsani)

Rohr even had a good word for my situation. "At last, one has lived long enough to see that 'everything belongs' — even the sad, absurd, and futile parts," he wrote in Falling Upward. "In the second half of life, we can give our energy to making even the painful parts and the formally excluded parts belong to the now unified field."

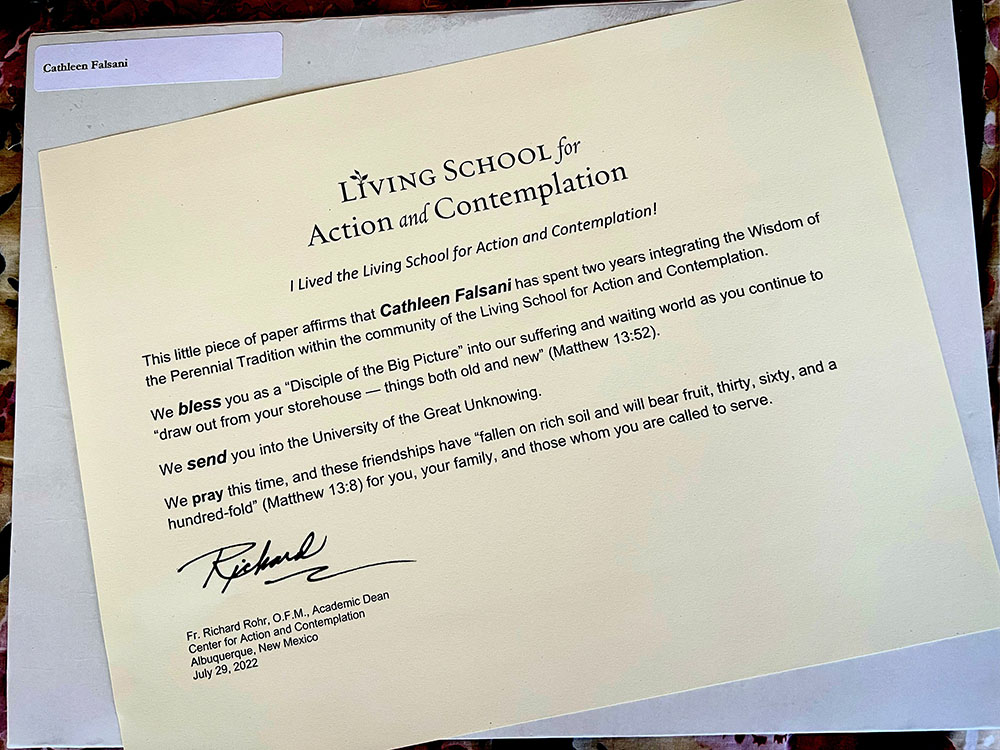

In the second half of my life, he assured me, all the seemingly disparate parts of my life and spiritual journey fit and made sense. I had to transcend earlier experiences, unlearn a few things, but include everything. Even the Southern Baptists, the mask of the Buddha I picked up in Nepal, and the rosary that was blessed by Pope Francis the night of his election when I stood among a scrum of other reporters in the rain taking notes and witnessing history. In my story, the Living School taught me, all of it belongs.

Established in 2013, the Living School has helped more than a thousand adult students create "deep engagement with their truest selves and with the world." Through contemplative practice and study of the mystic tradition inside Christianity and beyond it, the school aims to invite students "to awaken to the pattern of reality — God's loving presence with and in all things."

The school has four core faculty members: Rohr; the Protestant author/activist and theologian Brian McLaren; the Catholic mystic, Thomas Merton scholar and clinical psychologist James Finley; and the contemplative activist, author and theologian Barbara Holmes, who focuses on African American spirituality, mysticism, cosmology and culture. These four were also joined during the first year of my studies by the Episcopal priest, author and mystic the Rev. Cynthia Bourgeault, and, at the tail end of my studies, by the author, translator of the mystics and a leading voice in the interspiritual movement, Mirabai Starr.

In the pre-COVID "before times," if you will, the Living School had a distance learning component. It is a school for grownups who are expected to be self-starters and invested enough in their education to read and study and integrate the wisdom on their own without tests and quizzes or any kind of "proving." But there also were several large, in-person gatherings each year of the program, where students could connect face-to-face with their teachers and each other. The pandemic scuttled that for my cohort, the only one to spend its entire tenure under COVID-19's pall, when all but our final gathering relocated to Zoom.

A group photo of most of the members of the 2022 and 2023 cohorts of the Living School, taken in a courtyard of the inn at Albuquerque, New Mexico, in late July (Courtesy of the Center for Action and Contemplation)

At times, that made keeping up and feeling connected to my classmates and our studies more than a little challenging. Even though our class of about 200 was broken into small "circle groups" of about 10 people each, with whom we met regularly via Zoom to talk about what we were learning and our lives in general, and while we were grateful for the technology that allowed us to do so, it was a wan substitute for being together in person.

In late July, when we finally were able to be together physically for a five-day symposium in Albuquerque that marked the end of our cohort's studies, all the pieces fit together in a way I'd never before experienced. The wisdom imparted to us through the voices of St. John of the Cross, St. Thérèse of Lisieux, Thomas Merton, Julian of Norwich, the Desert Mothers and Fathers, Howard Thurman, Thich Nhat Hanh, Ken Wilber, Ilia Delio, McLaren, Holmes, Bourgeault, Finley, Starr and so many others took on flesh and walked among us. Hugging the people I'd been praying and sharing an intimate spiritual journey with for two years for the very first time was a precious gift, cool spring water after a drought that felt interminable.

When McLaren challenged us to not judge others, when Starr told us that grief is a spiritual practice, or when Finley urged us to ask ourselves, "All things considered, what is the most loving thing I can do right now?", we could see, hear, feel their intentions and our own in the way humans are only truly able to do when they're in the same room. And when Rohr made his first entrance, arriving with a health aide and his canine companion Opie by his side, he was a living, breathing master class of how to be fully present, not reactionary, and hold everything loosely — a lesson Mother Nature has been trying to teach the whole of humanity in the last couple of years.

Cathleen Falsani's certificate from the Living School (Courtesy of Cathleen Falsani)

Only a few times in my half-century of life have I been blessed with the awareness of something coming full circle, to see and understand the spiritual growth that has taken me from there to here. That week in Albuquerque was full of such numinous, transformational experiences. A turning point in a thin place.

"God put us on this earth for a little space, to bear the beams of love," Rohr, paraphrasing the poet William Blake, told several hundred students assembled in the Hotel Albuquerque ballroom for the final event of the week: our "sending" as students who had completed their studies (or at least their sojourn) at the Living School.

"It's all an enduring, an allowing — allowing the beams of infinite love to come toward you. In every event, in every setting, in every relationship, and even in your own mishaps and faults and mistakes," he continued.

For 79-year-old Rohr, who has been using a wheelchair of late after battling a few health issues, and for the Living School students, faculty and Center for Action and Contemplation staff, the July ritual marked the end of a chapter in their lives, and the beginning of something new. There is a student group just behind mine, the 2023 cohort, but none after that. For now, the Living School admissions process has been put on hold while Rohr and his colleagues discern what is to come next and how.

"May you know the height and the length and the depth and the breadth, may you know the love that surpasses all knowledge," said Rohr, lifting a hand from his cane and blessing us with the sign of the cross. "And may you know that you are infinitely children of God."