(Unsplash/Waldemar Brandt)

I originally wrote this column about the Epiphany. It seemed a fitting topic for the end of the Christmas season. Then, I got hit by a car. There's no obvious reason why a pedestrian mishap would translate to rewriting a column, but perhaps it will become clearer when I explain what it feels like.

You are crossing the street. You have waited for the light. You have looked both ways. The only cars approaching are far away — far enough, your mind registers, to slow down in plenty of time. You have crossed the street a hundred times, on errands too trivial to require much thought or purpose.

At first, it's only out of the corner of your eye, that you notice something is wrong — something is out of the ordinary. The car is not slowing down. It will slow down, though. It doesn't. In one moment, while it's still a little way off, the balance shifts from not-a-catastrophe-yet, to inescapable-catastrophe-barreling-towards you. In the final moment before it hits you, its size and speed and metallic efficiency swell to fill the world. The sheen of it, the screech of the brakes, the immense power it carries, are the realest things you have ever known. How could you have gone through your life without ever touching reality, without ever knowing that reality is this gleaming silver Subaru, hurtling down the street to kill you? You have no to time to move; you have all the time in the world to think, "I am going to die today."

When, after an eternity of waiting, contact occurs, it feels like reality, terrifying and shattering and exhilarating and definitely the reason you will die today.

Advertisement

I did not die. I was knocked down, bruised, shaken; I am told other injuries may manifest themselves over the course of the next few months. But I was alive. I exchanged information with the driver, refused offers to call an ambulance, walked into the nearest restaurant, and ordered myself steak tartare.

It seemed impossible, as the adrenaline ebbed out of my body, that such a thing had happened, at such a time, to me. What if I had crossed at a different crossing, or left my home later, or gone a different route? And yet it seemed equally impossible that I could have avoided that moment, that encounter with an adversary who felt as destined for me as the dragon in a fairy tale is for his knight.

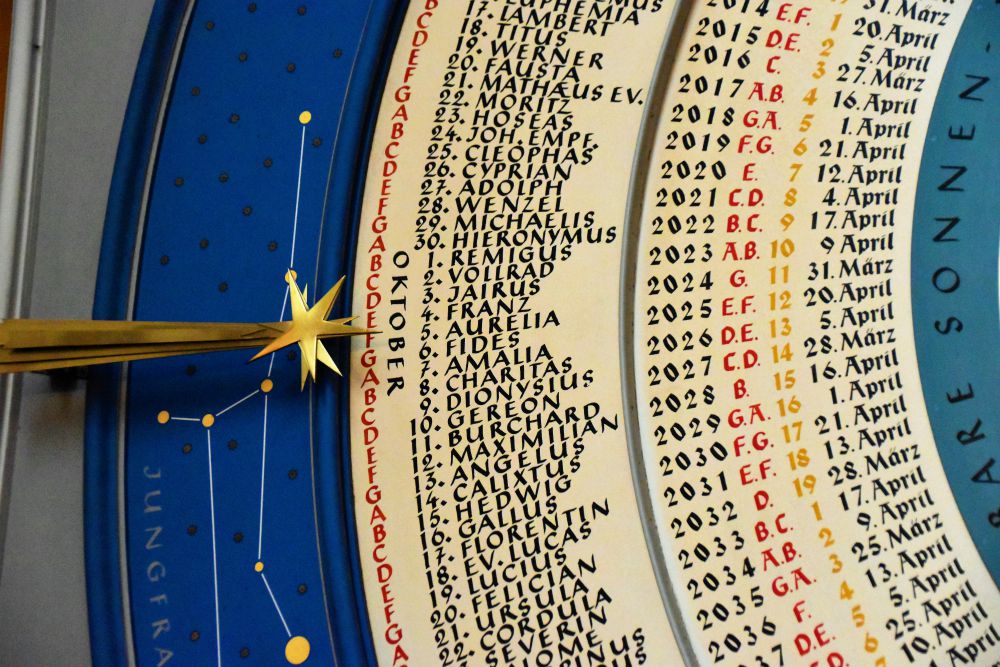

Interest and belief in astrology is, by all accounts, increasing in our culture. Commentators and critics have offered several explanations for its resurgence, all of them interesting. But there is an obvious, and I think therefore overlooked reason, which is that the stars are very real. They exist trillions of miles away, and they fill our world with radiance. They cannot be touched or controlled; their movements govern our seasons. They are the subject of a thousand songs and stories, and they will utterly outlast each of us. In the sub-lunar world of fluctuation and spectacle, their beauty (if you are lucky enough to see it away from light pollution) cannot be denied or trivialized or changed. To say that the stars influence the minutia of your life is to say that each ephemeral moment and contingency is pulsing with reality, a granular instance of an immortal cosmos.

(Unsplash/Calwaen Liew)

The three Magi who visited Christ were, by legend at least, astrologers. A star had risen in the sky, announcing the birth of the King of the Jews, and so they left their own land to pay him homage. According to Matthew:

When they had heard the king [Herod], they set out; and there, ahead of them, went the star that they had seen at its rising, until it stopped over the place where the child was. When they saw that the star had stopped, they were overwhelmed with joy. On entering the house, they saw the child with Mary his mother; and they knelt down and paid him homage.

What a strange incident — to find oneself caught up in a cosmic drama, to correctly divine the riddles of the ancient stars. And then, after all the solemn pilgrimage, to finally arrive such an ordinary domestic scene — a baby and his mother. The Gospel itself notes no discrepancy. They were overwhelmed with joy to see that the star had stopped. They asked no questions and emptied their chests. Was it trust in the star? Or did they already perceive in the baby's dimpled flesh the unmistakable presence of reality, reality that could put the stars to shame?

There is no particularly good way to wrap up a story of getting hit by a car, because there's no particular moral to getting hit by a car. It meant something to me, but that doesn't mean it meant anything in itself. If anything, the puzzle is how to reconcile such a banal incident with the feeling of having passed through something momentous. The answer, of course, is death, the predestined adversary, the reality principle for all creatures under the moon. It was death's passing, disinterested touch that electrified my hand.

At a different point in my life, I might have chased encounters with death — not suicidally, but hoping for just that lightest, electrifying touch. Like many others, I have spent my time throwing my soul in front of cars, so to speak, hoping to encounter something real. But death is not the most real thing. Death's conqueror is real, the Word made flesh. By him the stars were made, for us he became the subject of their omens. He came into the world so that we might have life, abundant and everlasting. He appears in ordinary and incongruous places, and it's worth the wandering of a lifetime if in one cataclysmic moment, we find him biding quietly, and adore.

[Clare Coffey lives in the Philadelphia area. She teaches kindergarten at a small Catholic school.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time a Young Voices column is posted to NCRonline.org. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.