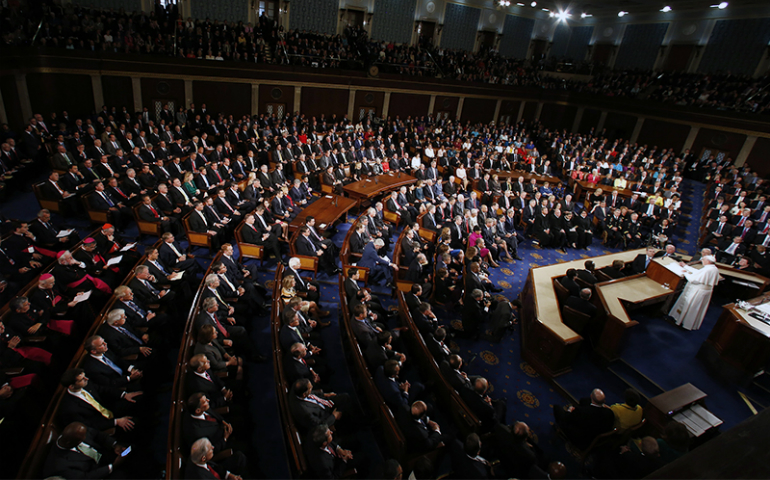

Pope Francis addresses a joint meeting of the U.S. Congress in the House Chamber on Capitol Hill in Washington on Sept. 24, 2015. (Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)

The United States Congress is about as Christian today as it was in the early 1960s, according to a new analysis by Pew Research Center.

Nearly 91 percent of members of the 115th Congress convening Jan. 3 describe themselves as Christian, compared to 95 percent of Congress members serving from 1961 to 1962, according to congressional data compiled by CQ Roll Call and analyzed by Pew.

That comes even as the share of Americans who describe themselves as Christian (now at 71 percent) has dropped in that time, Pew researchers noted.

And, as a whole, Congress is far more religiously affiliated than the general public.

"Why have the 'nones' grown in the public, but not among Congress?" asked Greg Smith, associate director for research at Pew, referring to people who check "none" on surveys asking their religion.

"One possible explanation is people tell us they would rather vote for an elected representative who is religious than for one who is not religious."

Smith pointed to past Pew polls, including one in January 2016 that asked whether voters were more or less likely to vote for a presidential candidate who does not believe in God. More than half said they'd be less likely to vote for a nonbelieving candidate, 10 times the number who said they'd be more likely to vote for such a candidate.

And in 2014, Smith said, 60 percent of adults in the U.S. told Pew it was important to them that members of Congress have strong religious beliefs.

"Being a nonbeliever really is a political liability," he said.

While the new 115th Congress mostly looks like the last (and the 87th that convened in 1961), the new Congress does include seven fewer Protestants, four more Catholics and six fewer Christians as a whole.

That mimics a shift in the general public, according to Aleksandra Sandstrom, copy editor and lead author of the Pew report: Like the rest of the country, Congress has become less Protestant. The share of Protestants in Congress has dropped from 75 percent to 56 percent since the 1960s, while the share of Catholics has jumped from 19 percent to 31 percent.

And 13 percent of its new members affiliate with non-Christian faiths, nearly double the share of non-Christian incumbent members, according to Pew. More than half of those non-Christian freshmen are Jewish (8 percent), the largest share of Jews in any freshman class, researchers noted, though Sandstrom said that data only was available back to 2011-2012.

'Nones' underrepresented

Christians, both Protestant and Catholic, aren’t the only demographic to outstrip the general population in Congress. There also is a larger share of Jewish members of Congress (9 percent) than there is of Jewish Americans in the country as a whole (2 percent).

Representation by Buddhists, Mormons, Muslims and Orthodox Christians in Congress is roughly proportional to their population size.

But the growing number of religiously unaffiliated Americans, including atheists and agnostics, remain underrepresented.

The nones make up 23 percent of all Americans, according to Pew, but just 0.2 percent of Congress: Only Rep. Kyrsten Sinema, a Democrat from Arizona, describes herself as religiously unaffiliated.

That's "literally 100 times" as many religiously unaffiliated Americans as there are religiously unaffiliated members of Congress, pointed out Casey Brescia, communications associate for the Secular Coalition for America.

There are more atheist Americans (just over 3 percent) than Jewish (again, 2 percent) or Muslim, Hindu or Buddhist (each, less than 1 percent), according to Pew's latest U.S. Religious Landscape Study.

Sinema does not identify as a nontheist, atheist or nonbeliever, which means there are no openly atheist members of Congress and haven’t been since Rep. Pete Stark, a Democrat from California, was voted out of office in 2012, Hemant Mehta wrote on the Friendly Atheist blog.

"There is a price for running as an openly nonreligious candidate, but it's not nearly as significant as it was in the past, and it's not nearly as prohibitive as a lot of lawmakers are reluctant to openly express their lack of faith or run as nonreligious candidate," Brescia said.

By the Secular Coalition for America's count, he said, at least 11 openly religiously unaffiliated candidates won state offices and many more ran in the 2016 election cycle.

Differences in chambers, parties

Religious affiliation differs in the House of Representatives and the Senate, and by political party.

"Of the non-Christian members of Congress, most of them are in the House and most of them are Democrats," Sandstrom said. "There are only two non-Christian Republicans in Congress, and one of them is a new member of Congress, so the non-Christian contingent doubled between the last Congress and this Congress."

All but two of the 293 Republicans in the new Congress are Christians. Those are Rep. Lee Zeldin of New York and Rep. David Kustoff of Tennessee, both of whom are Jewish.

The 242 Democrats in Congress also overwhelmingly are Christian (80 percent). But Democrats also include 28 Jews; three Buddhists; three Hindus; two Muslims; one Unitarian Universalist; Sinema, the one religiously unaffiliated member of Congress; and 10 members who declined to state their religious affiliation, according to Pew.

"It's also of note that the majority of the non-Christians in Congress are Jewish," Sandstrom said. "In all the years we've analyzed, all of the Republicans in Congress who have not been Christian have been Jewish."

Both the House (91 percent) and Senate (88 percent) are majority Christian — specifically, Protestant (55 and 58 percent, respectively). One-third of the House is Catholic, compared with one-quarter of the Senate, and all five Orthodox Christians in Congress are members of the House.

The Senate includes just nine members of non-Christian faiths: Eight are Jewish, and Sen. Mazie K. Hirono, a Democrat from Hawaii, is Buddhist.

CQ Roll Call compiled its data through questionnaires and follow-up phone calls to Congress members’ and candidates’ offices, according to Pew.