Tourists and townspeople surround a statue of St. Benedict Aug. 14, 2013, in the small Italian town of Norcia. (CNS/Henry Daggett)

Since Rod Dreher's The Benedict Option was published in 2017, St. Benedict's name has surfaced in discussions on faith and secularism. In honor of this feast of St. Benedict, I wanted to look more closely at St. Benedict's actual options — and his decision to live a monastic life in a cave at Subiaco.

I'm already somewhat familiar with Benedictinism; I've had experience working at educational institutions run by Benedictine monks. Having spent time with the monks at prayer and reading The Rule, I've gotten a sense of what Benedict was really about. Nevertheless, I was curious to find out more about the man myself, which led me to undertake a pilgrimage to il Sacro Specco.

As I hiked the mountain that led to the sacred cave, I prayed for my students, co-workers and the monks who run our school. I asked that we find ourselves more united to God and to each other over the course of the next school year.

When I reached the top, I was surprised by the beauty of the monastery (which was built into the mountain) and the landscape. After snapping a few pictures and offering some more prayers, I started making my way back down.

The cover of The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation by Rod Dreher (CNS)

Then it occurred to me: there must not have been much to do up here, isolated in this mountain. I guess Benedict's motto was accurate: ora et labora, prayer and work. Other than that, there's nothing else he could have really done. So how did he end up initiating a cultural and spiritual revolution that continues to impact the world 1,500 years later? My being employed at a Benedictine school and the not-too-distant hype around The Benedict Option made this question even more pressing for me.

Benedict must not have intended to start such a revolution; most revolutionaries don't set out to change the world by spending hours on end reciting the psalms and taking care of mundane chores. His "revolutionary attitude" certainly contradicts my mentality when facing the problems in front of me that need to be "revolutionized" — whether it's the worsening fragmentation of American society or the hardships my students are facing. To me, making a difference in the world or in someone's life starts with a plan or a project. I have to devise the perfect way to fix the problem in front of me. If I don't, I feel like a failure.

I often saw this attitude taking form in the way I taught my classes. My desire to help my students find God and make sense of their lives turned into some big plan for the "perfect lesson" in which they would finally understand the truth. What ends up happening every time I come up with a new perfect lesson is that the students get bored. There always seems to be a disconnect between what I think they need and what they feel they need.

That's when I realized the main difference between Benedict's and my attitudes toward revolution. Benedict knew he didn't have any answers. He knew that he hadn't the key to "fixing" the decay of Roman society. Only God had the answers. And only a life devoted to God — through prayer and work, through being attentive to what God has placed in front of him and obeying what was asked of him — would any real solution emerge.

Advertisement

My attitude was centered on constructing an answer of my own and imposing it onto the problem. I too readily assumed that I am an adequate agent of change, that I can presume to know the answers to other people's (and my own) issues and can act as a savior. In reality, I don't know what other people need. I can't save anybody. All I can do is pay attention to them and "obey" the circumstances in front of me, asking God to reveal himself to me with each "yes."

As I returned to work after my trip, I was faced with a question: What will benefit my students? Is it me trying to make a difference in their lives by coming up with the perfect lesson, the perfect solution to their problems? Or is it me "obeying" reality in the Benedectine sense — paying more attention to them and less to the little details of planning my lessons?

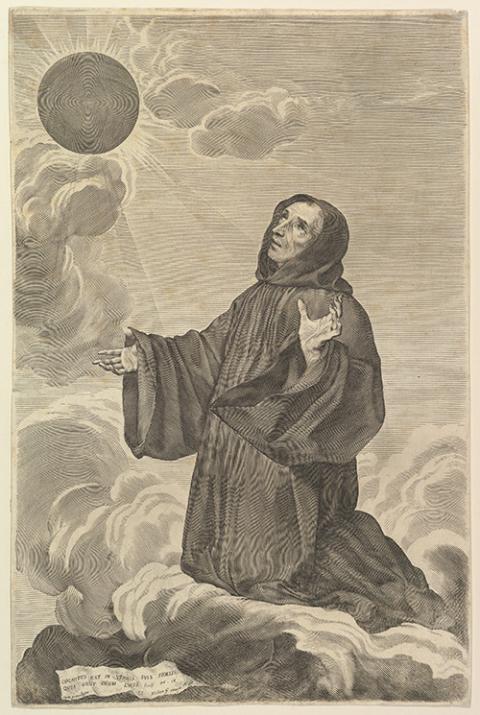

"St. Benedict in Ecstasy," by Claude Mellan (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

I decided to follow the latter option, knowing it's the one Benedict would've chosen. I hesitated at first at the implied risk. If I give up my idea of the perfect lesson or solution, I have to abandon myself to the will of Someone other than me; Someone mysterious and unpredictable. I was letting go of control. Little did I know the freedom I would gain from this risk.

I started to find that my students were becoming more trusting of me, and that I was receiving less resistance and frustration from them. The disconnect was being bridged because I started to listen more closely to them and to understand their actual questions and needs. My lessons became more solid as I spent more time fleshing out the details and based them on the concerns my students were communicating to me rather than the ones I assumed they had.

For example, I started my unit on Christology with the first chapter of John's Gospel in which Jesus asks John and Andrew, "What are you looking for?" My students were fascinated by this question. "No one ever asks us that," they said. Then I moved to the next lesson on the Samaritan woman at the well. They were unimpressed by her story, and asked to talk about Jesus meeting John and Andrew. At first I hesitated — spending more time on John 1 wasn't in my lesson plans. But this is when I realized I had to make a choice: either stick to my plan or obey what was happening with my students.

Following Benedict's method of obedience to the little details God placed in front of him was … effective and satisfying. Perhaps this is why his charism continues to impact the world 1,500 years after the fact. His method was rooted in his trust in God and not in his personal schemes of changing the world.

I decided to take more time looking at the existential questions Jesus asked. They were so enthralled that I decided to base their midterm project on this topic. I was amazed by the work they produced — and I ended up learning from them.

I came to the conclusion that my big ideas, as exciting as they may feel to me at the moment, will never stand the test of time. Following Benedict's method of obedience to the little details God placed in front of him was much more effective and satisfying. Perhaps this is why his charism continues to impact the world 1,500 years after the fact. His method was rooted in his trust in God and not in his personal schemes of changing the world.

With all this talk about The Benedict Option that continues to swirl around Christian circles, I strongly recommend we pay closer attention to Benedict's actual "option." We don't all need to go on pilgrimage to Subiaco to understand it. We only need to be willing to learn from his example and have the humility to trust that praying and working is enough; that what He gives us, what He asks us to say "yes" to, even if it seems mundane and miniscule, is enough to change ourselves and those around us.