Unsplash/Dmitry Kotov

In April 2006, the Vatican Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith notified Vietnamese-American theologian Peter Phan that his 2004 book, Being Religious Interreligiously: Asian Perspectives on Interfaith Dialogue was "confused" on significant points of Catholic doctrine. A year later, the Committee on Doctrine of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops restated the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith's allegations. The unreasonable timelines mandated in each case made it impossible for Phan to respond.

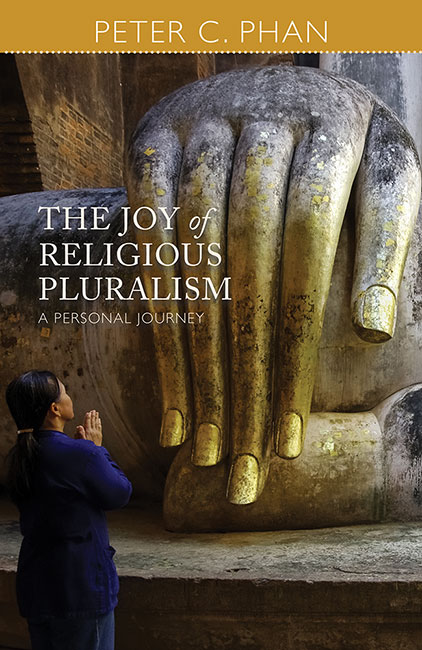

Now, after 11 years, Phan has published the book-length "clarification" demanded by the two entities. The Joy of Religious Pluralism is, in large part, a response to the congregation's assertion that Being Religious Interreligiously "is in open contrast with almost all the teachings of Dominus Iesus," the 2000 Vatican declaration on the "unicity and salvific universality of Jesus Christ and the church."

Phan is a leading Catholic theologian, the first Asian-American president of the Catholic Theological Society of America and recipient of its distinguished John Courtney Murray Award. He is best known for his work on Asian and Asian-American theology and interreligious dialogue, but he is also an expert on Eastern Orthodox iconography, patristics, Karl Rahner and liberation theology.

The heart of Phan's theology of religious pluralism is the complementary relationship he perceives between Christianity and non-Christian religions. Only through a sincere and humble dialogue with other religions, Phan believes, can Christianity come to a full realization of its own identity and calling. In this context, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and the Committee on Doctrine find particularly problematic Phan's positions on Jesus Christ as the unique savior, the salvific significance of non-Christian religions, and the church as the exclusive sacrament of salvation.

Unsplash/Sabine Schulte

The first two chapters of The Joy of Religious Pluralism establish a wider framework for discussing these three issues. In Chapter 1, Phan addresses the inadequacy of the hierarchical conviction that the only way to do theology is to apply the episcopal magisterium — Scripture and tradition — to whatever matter is under consideration. Phan shows that, depending on the question at hand, some or all of the four other magisteria — those of the theologians, the laity, the poor, and believers of non-Christian religions — must also be considered to achieve authoritative teaching.

In Chapter 2, Phan explains that the foundation of Christian theology is the Divine Spirit, who acts in history through both "hands of the Father," the Son and the Holy Spirit. And while the actions of these two hands are interdependent, they are also autonomous. Thus the Holy Spirit was at work before the Son was incarnated in Jesus of Nazareth and is at work after that incarnation, and even outside it, including in the wisdom of other religions.

Phan situates the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith's concern regarding his treatment of the salvific universality of Jesus Christ within this framework. Because of its failure to draw on the magisterium of other religions, Phan explains, the congregation is unable to see that the hand of the Spirit was active in some of those religions even before the incarnation of Jesus Christ and is active in their salvific symbols today. Only through a pneumatological Christology, one that learns from the messianic representations in Buddhism, Hinduism and the other religions, will the church come to a full understanding of Jesus Christ as savior.

Advertisement

Unsplash/Niels Steeman

Similarly, Phan explores the salvific significance of non-Christian religions and the universality of the Catholic Church in light of multiple magisteria and the Divine Spirit. The magisterial officials who make pronouncements on the objective deficiencies of non-Christian religions, as they do in Dominus Iesus, have clearly never had their Christian faith deepened by the holiness of members of other faiths as Phan has. Just as Jesus Christ humbled himself by becoming human (Philippians 2), Christianity is called to a kenotic (self-emptying) theology in which it renounces its assumed superiority over other religions. The mission of the church, then, is not "to the gentiles" but "with the gentiles," collaborating with members of other religions to bring about the reign of God.

Phan also notes similarities between his interreligious theology and the teachings of Pope Francis. He points out, for example, that in "The Joy of the Gospel," Francis uses terms like "confusion" and "complementary" in ways that, when Phan used them, elicited the condemnation from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Maybe with a newly appointed head of the congregation, these critiques of Phan will just melt away.

Phan's interreligious theology makes a significant contribution to the church in the 21st century, moving the church as it does from the Eurocentrism of its last millennia to the multi-cultural, globalized reality of today. Without meaning in any sense to minimize this contribution, I do, however, have one concern. In his preface, Phan maintains that The Joy of Religious Pluralism is aimed at a general readership. But the nuance and complexity of the questions Phan raises make the book extremely challenging in places.

Unsplash/Chinh Le Duc

Phan states repeatedly, for example, that to acknowledge a complementary relationship between Christianity and other world religions is not to claim that the teachings of those religions are in any sense equivalent. His theology, he assures us, is not relativist. But the very need to offer this reassurance multiple times suggests the difficulties that Phan's arguments may present to the "general reader."

On the other hand, Phan does a masterful job of using his personal experiences — his life as a refugee from Vietnam, his encounters with practitioners of other religions — to weave The Joy of Religious Pluralism together. And there's no denying that he's a wickedly funny theologian. More than once, a good laugh untied the knots in my theological brow as I read his book. In the long run, the importance of Phan's interreligious theology, supplemented by his humor, more than offsets the complexity of his arguments.

[Marian Ronan is research professor of Catholic Studies at New York Theological Seminary in New York City. Her seventh book, Women of Vision: Sixteen Founders of the International Grail Movement, co-authored with Mary O'Brien, was published by the Apocryphile Press earlier this year.]