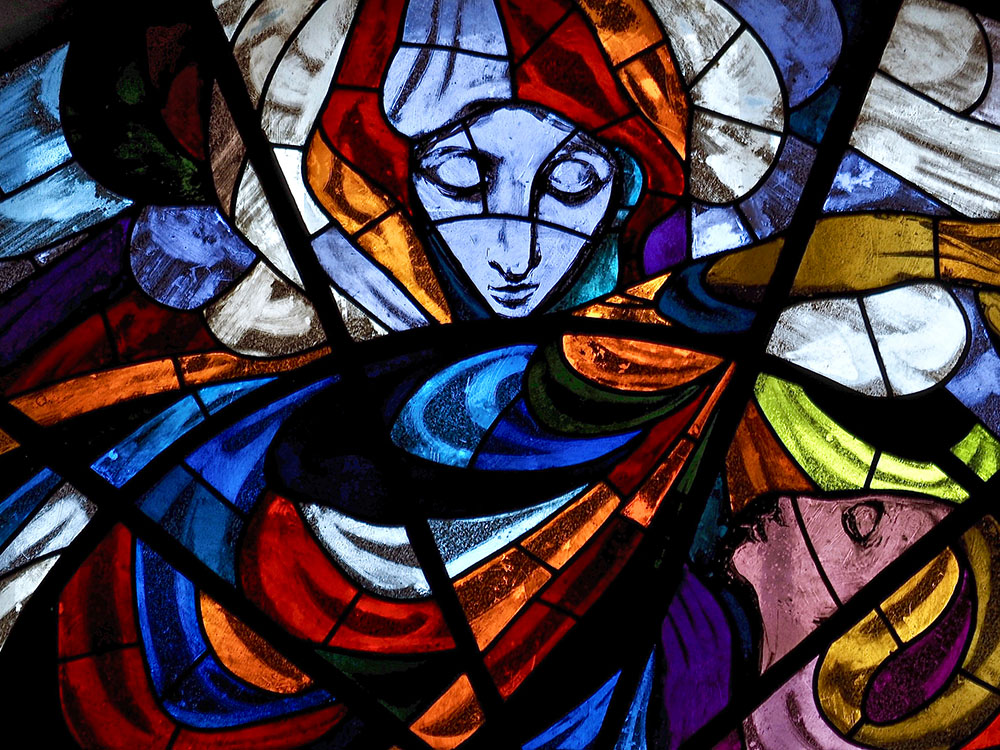

(Dreamstime/Marion Meyer)

I will be 80 years old in June. As a young child in the Methodist Church, I was certain I was called to ordained ministry. At Duke University, I majored in religious studies and then served as pastoral assistant and director of religious education in a small church in upstate New York. Then, in the summer of 1967, I went to Tucson to study creative movement expression education at the Tucson Creative Dance Center.

Now, where would I go to church? There was time and opportunity to explore.

I visited the Methodists, the Presbyterians and the Lutherans, but no particular place beckoned. I had already ruled out the Catholic church — but then the maintenance man at the dance center convinced me to give it a try. "Go to a 6 a.m. Mass. You'll still have time to go somewhere else after that."

I snuck into a back pew at 5:45 and knelt down, unprepared for what was to follow. The priest appeared, looking like he had just rolled out of bed, kissed the altar, mumbled, "The Lord be with you," and then snorted and wiped his nose across the sleeve of his alb!

What immediately went through my mind was, "These people are not here for this man, They must be here for ... God!"

Laugh if you will, but I knew at that moment I would become a Catholic. What about my call to ordination? No worries. It was 1968. Vatican II. Change was in the air. All I had to do was be patient. Ordination of women was just around the corner.

A few years later, I was a full-fledged Catholic. I worked at a parish school for more than 15 years, first as a teacher and then as a liturgist. When it came time for a change, I took a year off to write and live under private religious vows, supplementing my savings with part time jobs.

Advertisement

Over the years, I earned a master's in pastoral ministry from the University of San Francisco, along with certificates in spiritual direction and therapeutic harp work.

I then went to work for 15 years as a certified music practitioner, playing my harp at the bedside of patients at a hospice inpatient unit. It was a "holy ground" experience. The unit felt like a church, and the patients like beloved parishioners.

The hospice was looking to increase its number of chaplains, so I enrolled in the ordination program at the New Seminary for Interfaith Studies, a two-year, low residency program in New York City. There were three women in the accelerated program — all three of us Catholic! All denied ordination by our own church, nevertheless grateful for this path to ordination as interfaith ministers.

After retirement from hospice, and until COVID-19 shut everything down, I volunteered weekly as a chaplain and bedside harpist at a Tucson hospital.

Now I write for the Keeping the Faith section of the Sunday edition of the Arizona Daily Star, drawing on the many years of work for the Catholic church and the broader Christian community.

I have no complaints. But I will forever ask, "Why?" Why couldn't I be ordained by my own church for service in hospice, hospital, a retreat center, the military, a women's prison, a battered women's shelter, a parish church?

I do not see myself as a victim of an intentionally discriminatory church, but as a keeper of the vision in an institution that has yet to deal scientifically, scripturally, theologically, morally or justly with women.

Some women tell me that because women's ordination may not happen in their lifetime, they cannot stay in the church. But as for me, I know this is not a matter of "my" lifetime, nor is it about "me." It is about the call and the vision that will be realized in its time. And I have a responsibility to hold and give voice to that vision while I am able despite my accumulating years.

I cannot leave a church that feeds me liturgically and sacramentally, one that nourishes my soul with ancient wisdom and profound practices of prayer, contemplation and spiritual pilgrimage.

I will continue to voice the vision because if I do not, I will not be the person God has created me to be. And because when a vision remains unvoiced, and a call goes unanswered, the church is poorer for it.