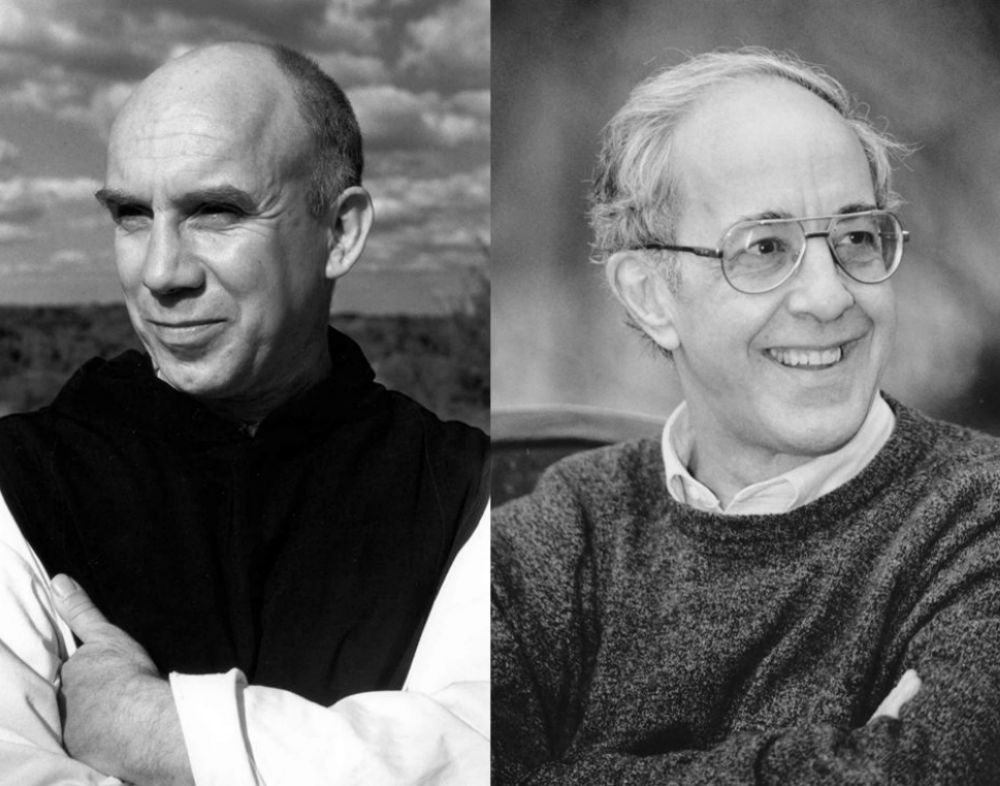

From left: Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton (1915-1968) and Dutch Fr. Henri J.M. Nouwen (1932-1996) are pictured in two undated photos. (CNS/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University and NCR archives, published 1998, respectively)

Speakers at a weekend colloquium billed Fr. Henri Nouwen as "the most popular of spiritual writers and guides of the last half century" as some 170 participants flocked to Yale Divinity School seemingly to look deeper into where spiritual life was leading them.

Although dead for over 20 years, Nouwen still cut an imposing figure on the campus at the "Henri Nouwen and Thomas Merton: Spiritual Guides for the 21st Century" conference Nov. 3-4. Several participants remembered how Nouwen "changed my life" or recalled the maple tree under which he gathered students or the space at the back of the common room where he daily celebrated the Eucharist during his 1971-81 tenure here.

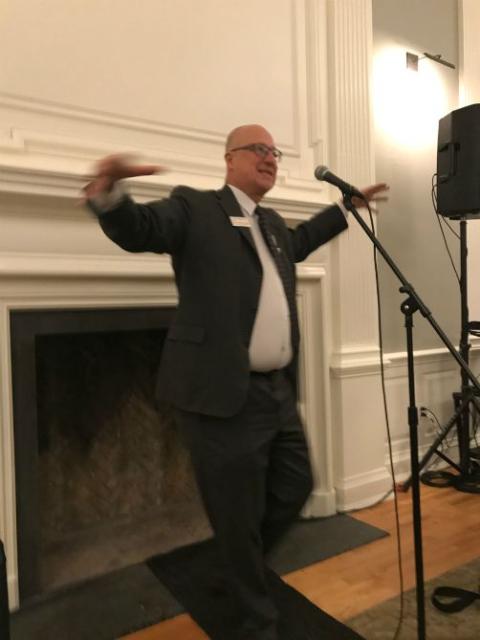

James R. Hackney, Jr., a 1979 Yale Divinity School graduate — now the school's senior director of development — demonstrated with open arms and expansive gestures just how engaging were Nouwen's lectures and teaching style. Hackney opened an evening session recalling Nouwen's charisma and was joined by a number of Nouwen's former students.

Both Catholic priests, Nouwen and Merton centered their lives on the Eucharist. Both were deeply responsive to the suffering of others, said Jim Forest of Alkmaar, the Netherlands, who knew Nouwen and Merton, calling them "spiritual parents" during certain periods of his life. Both priests were excellent confessors and counselors, he said, adding that "both made it possible for me to reveal parts of myself that were painful, awkward and embarrassing."

Nouwen, born in the Netherlands, and Merton, born in France and educated in Britain, were at home on two U.S. secular campuses — Yale for Nouwen and Columbia University for Merton, where he completed both his undergraduate and master's degrees in the 1930s and became a Catholic at nearby Corpus Christi church in 1938. Nouwen later taught at the Harvard Divinity School in the 1980s.

Merton and Nouwen authored more than 100 books between them, which have sold some 22 million copies and been translated into more than 30 languages.

James Harvey impersonates Nouwen's long arms and teaching style. (NCR photo/Patricia Lefevere)

The priests wrote the books at a time when the word "spirituality" wasn't really present in the English language, said Oblate Fr. Ron Rolheiser, himself a leading spiritual writer and teacher in the Merton-Nouwen tradition. Rolheiser, president of the Oblate School of Theology in San Antonio, recalled how restricted was the concept of spirituality in Catholic circles when these men were first writing their books — from the late 1940s to the mid-1990s — and how suspect was the notion of spirituality in Protestant and Evangelical circles.

But their pioneering work has spawned a large swell of spiritual writers and led to a growing acceptance of the genre in Catholic, Protestant and Evangelical milieus. The gradual — if often reluctant — acceptance of spirituality as a respected academic discipline has led to the birth of schools of theology and institutes whose mission it is to teach spirituality, even award doctorates in it, Rolheiser added.

Rolheiser called Nouwen "a struggling saint, one-in-progress," adding the priest never fit the pious profile of a saint though he was always recognized as a deeply spiritual man.

His readers identified with him because Nouwen shared his struggles so honestly. "He related his weaknesses to his struggles in prayer and, in that, many readers found themselves looking into a mirror." When Rolheiser first read Nouwen, "I had a sense of being introduced to myself."

Bridge-builders

Eric Hung, an exchange student at Yale from the Chinese University of Hong Kong credited the translations of Nouwen by Wen Weiyao, a professor at the Chinese University, to the writer's popularity among Chinese of many denominations.

Advertisement

St. Joseph Sr. Monica Weiss (NCR photo/Patricia Lefevere)

The writings of Nouwen and Merton have become "bridge-builders" advancing ecumenical relations in Hong Kong, Lukas Cheung told NCR. Cheung, a student at the Yale Divinity School, said that prior to the reception of Merton and Nouwen among Chinese readers, Catholics, Protestants and Evangelicals had kept distant from one another.

The weekend at Yale Divinity School offered a glimpse of just how important the spirituality of these two men still is to the many assembled: men and women, young and old, lay and ordained from different confessions and a variety of occupations. Robert Ellsberg, publisher of Orbis Books, reminded the audience that both Merton and Nouwen were constantly restless spiritual explorers. Both men grew up in Europe, but lived more than 30 years in the United States and made many sojourns within America as well as traveling all over the world. Merton journeyed to Cuba, Bermuda, Rome and Asia while Nouwen lived in Bolivia, Peru, France and Canada.

Both were moving toward an interior geography of the soul, said Ellsberg, a long-time friend of Nouwen and who served for some years after Nouwen's death in 1996 as a member of his literary trust.

Ellsberg said that Merton realized his vocation was far more than being in a certain place — like the Abbey of Gethsemani where he lived 27 years — or wearing the habit of a Trappist monk.

"There are too many people in the world who rely on the fact that I am serious about deepening an inner dimension of experience that they desire that is closed to them," Merton wrote on June 22 1966. The passage is contained in volume 6 of his journals, Learning to Love: Exploring Solitude and Freedom.

"And it is not closed to me," Merton wrote. "This is a gift that has been given me not for myself but for everyone. … I cannot let it be squandered and dissipated foolishly. It would be criminal to do so."

On Sept. 10, 1966, Merton signed a short formula in which he committed himself "to live in solitude for the rest of my life." His resolve came following an affair he'd had with a student nurse when he was a surgical patient in a Louisville, Kentucky, hospital. While the temptation to abandon his vocation had vexed him for weeks, he returned, Ellsberg said, to the idea that had first attracted him to the abbey, to the idea that the monks through their prayers and their faithfulness, were in some way keeping the world turning

Robert Ellsberg (NCR photo/Patricia Lefevere)

Both men had a sense of their impending deaths, Ellsberg said, pointing to Merton's realization when gazing upon a huge reclining Buddha statue in Sri Lanka that "everything is emptiness and everything is compassion." A week later — Dec. 10, 1968 — Merton died in Bangkok, Thailand, electrocuted in his hotel room as a result of a faulty fan.

Ellsberg recalled that Nouwen stood in a crowded lecture hall in the 1970s in this very divinity school, jotted the date of his birth, 1932, then another date, 2010, on the board followed by a question mark. "This could represent my life," he told his audience. Neither he nor his students could guess how much shorter the actual line between the two dates would be, Ellsberg said. But Nouwen returned to the black board, drew a line from one end of it to the other and announced: "I have come from somewhere and I am going someplace else."

Nouwen was inviting his students and readers to accompany him on a journey ever deeper into the heart of the divine mystery, Ellsberg said.

"Whether Henri found the home he was seeking is something he alone knows," he said. "But in his prolific writings, as much as Merton, he left a trail for fellow seekers."

[Patricia Lefevere is a longtime NCR contributor.]