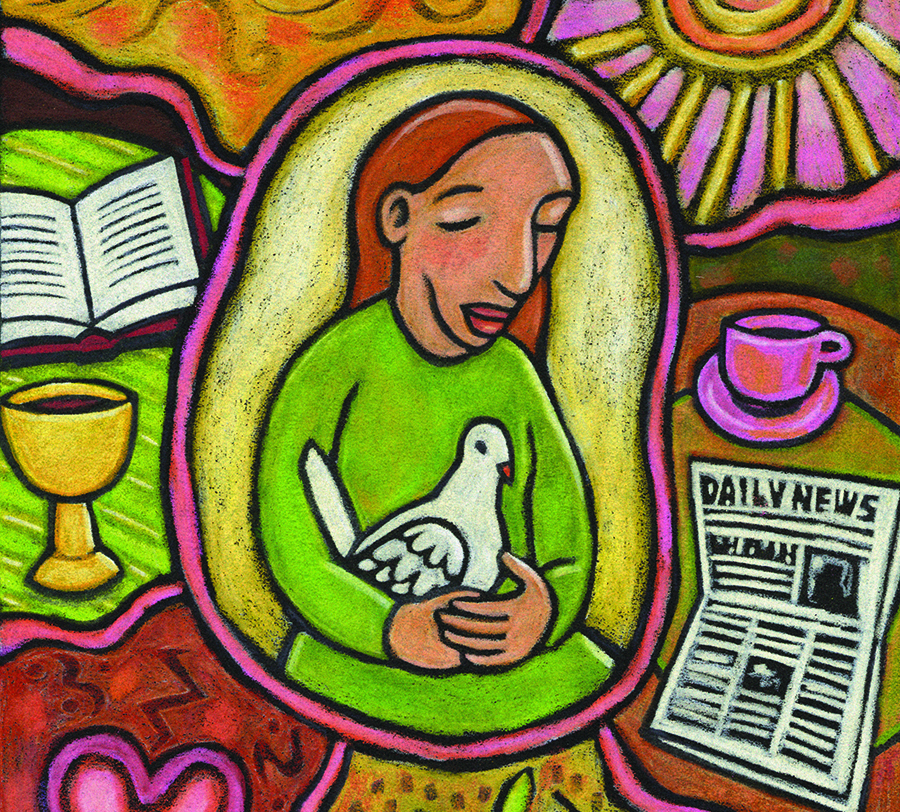

(Julie Lonneman)

We talk, we read, we write, we listen. We surround ourselves with print on paper and walls and screens. We surround ourselves with sounds-making-words that convey meaning and images. Except for the ones borrowed from spontaneity ("Ouch!") or nature ("whisper"), the image and the meaning of English words seem to us now to be mostly arbitrary: a tacit agreement that this sound will mean just this to both of us. Thus one generation gives words to the next, one age to another, one language to another.

We take the vocabulary and we run with it, but we should now and then pause to think of small but amazing facets of our words. When I say this or that little piece of sound, I may have said the same little piece that someone said a hundred or more generations ago with a meaning close to the meaning I have today.

For example, a way of combining the ever-useful "ah" with a hard "gah" with a round "oh" and quickly a soft "jah" leading to a resolving "eee." "agohjee" or (in our arbitrary way of English spelling, "agogy"). Or a hum of a "mmm" and then a tiny "ih" to get us to those two good friends "s" and "t." "Mihst," or "myst."

Two tiny sets of sounds, each having come together probably in many tongues with many meanings, but we know the particular coming together of these sets of sounds, and then the attachment of one to the other, that happened in the Greek language, then was borrowed from language to language including eventually our English. Put that "agohjee" after that "Mihst" and you have a young man asking his editor friends at Liturgy Training Publications 10 years ago: "OK, now just who is this Mister Gohjey that you talk about so much around here?"

That's a good question. Who indeed is Mister Gohjey? I've been trying to find that out in the pages of Celebration for several years now. The ancient combination of sounds is a clue. "Agogy" gives us something about leading or moving to or around or closing in on the "myst," whatever that reality was that eventually gave us the English words "mystic" and "mystery" and all their families.

The best I can manage in thinking about what this is and why we are looking for it could begin with a question: Isn't it strange that pre- and post-Vatican II, the content and manner and shape of the sermon/homily at the Sunday liturgy seem generally unaware of where it is and what it thus must be?

Apart from some attention to one (seldom more) of the scriptures that have preceded it, a lot of Sunday preaching could just as easily be printed text in the bulletin or a CD to play at home at any hour. It can float free because it never recognized its home, its context, its reason to be. Shape, content and manner are amazingly unaware of where they are and why they are, unaware of those actions to which they are meant to be integral. So this mystagogy gives us a way to think about what that shape and that content and that manner might mean to the preaching and the preacher.

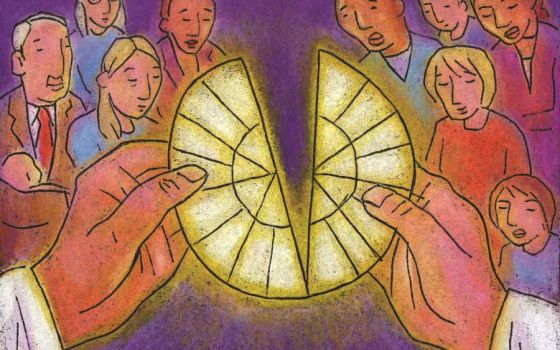

We cannot do well what we are meant to do Sunday after Sunday (to begin with) unless we try for some brief time to speak about it, to unfold again and again the poetry of our rituals. Can both homilist and assembly struggle to put into words what can be put into words? Can we struggle to find expression for what we mean as an assembly that, first of all, assembles, that listens to the scriptures, that intercedes and gives thanks and praise over bread and wine and shares and shares alike?

Our liturgy and we ourselves, who do the liturgy, are in need of some moments when we challenge ourselves to see if what we do here is in fact the expression and the longing of the assembly to which we were admitted at our baptism.

Post-Vatican II we frequently heard the exhortation to preach with the Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other, and that certainly helped. But perhaps it presumed what we cannot presume: that this preacher with both hands full is standing always in a moment and in a place, and that both attention to scripture and attention to the world will have to come to be spoken language within a given assembly that is right then and there trying to do what our baptized assemblies do on the Lord's Day if we are ever going to hold ourselves and the world together. That is, we are the world come together because this is what our baptism requires of us.

But then, from the start, you are in the midst of rites and rhythms, rhythmic rites and ritual rhythms. Sunday is our assembly day, the first and the eighth day, and each Sunday is named for a season or counted between the seasons. Some of what the assembly does is the same, in season or out. Some comes with the season. The counted Sundays have a way, always imperfect of course, of taking us through books of scripture so that even in Ordinary Time the preaching has to work on this continuity of reading from Romans or from whatever Gospel or letter (harder is the present Lectionary's use of the Hebrew scriptures).

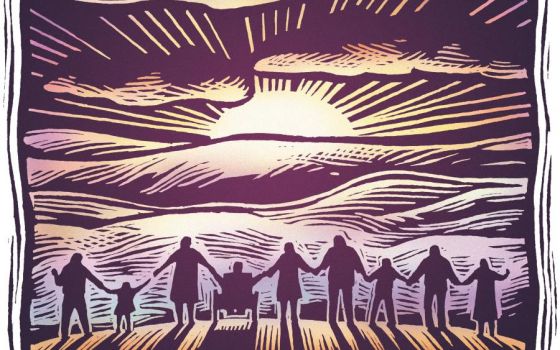

We recovered in the years after Vatican II a language long lost that understood once and can again that the mystery into which we are baptized (this Christ whom we have put on, or in other images, this Christ in whom we have died and in whom we now live) is also a name for our assembly (the church) and for the whole spectrum of rituals we are to know by heart in order to move ever further into our baptized life's calling.

These rituals are day by day (signing ourselves with the cross, pausing to give thanks at table, remembering and bringing to God in intercession) and week by week (Sunday) and year by year (fasting and feasting, initiating) and life by life (initiation, growing to maturity, sickness, death). And these also are named mystery, paschal or passover mystery, for we are not a church content with the ways of the world, or with our own ways in fact, but we find ourselves initiated little by little, even here at Sunday Eucharist, into ways to be and see and love and live for others.

Advertisement

The best I can manage in thinking about what this is and why we are looking for it could begin with a question: Isn't it strange that pre- and post-Vatican II, the content and manner and shape of the sermon/homily at the Sunday liturgy seem generally unaware of where it is and what it thus must be?

Apart from some attention to one (seldom more) of the scriptures that have preceded it, a lot of Sunday preaching could just as easily be printed text in the bulletin or a CD to play at home at any hour. It can float free because it never recognized its home, its context, its reason to be. Shape, content and manner are amazingly unaware of where they are and why they are, unaware of those actions to which they are meant to be integral. So this mystagogy gives us a way to think about what that shape and that content and that manner might mean to the preaching and the preacher.

We cannot do well what we are meant to do Sunday after Sunday (to begin with) unless we try for some brief time to speak about it, to unfold again and again the poetry of our rituals. Can both homilist and assembly struggle to put into words what can be put into words? Can we struggle to find expression for what we mean as an assembly that, first of all, assembles, that listens to the scriptures, that intercedes and gives thanks and praise over bread and wine and shares and shares alike?

Our liturgy and we ourselves, who do the liturgy, are in need of some moments when we challenge ourselves to see if what we do here is in fact the expression and the longing of the assembly to which we were admitted at our baptism.

Post-Vatican II we frequently heard the exhortation to preach with the Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other, and that certainly helped. But perhaps it presumed what we cannot presume: that this preacher with both hands full is standing always in a moment and in a place, and that both attention to scripture and attention to the world will have to come to be spoken language within a given assembly that is right then and there trying to do what our baptized assemblies do on the Lord's Day if we are ever going to hold ourselves and the world together. That is, we are the world come together because this is what our baptism requires of us.

But then, from the start, you are in the midst of rites and rhythms, rhythmic rites and ritual rhythms. Sunday is our assembly day, the first and the eighth day, and each Sunday is named for a season or counted between the seasons. Some of what the assembly does is the same, in season or out. Some comes with the season. The counted Sundays have a way, always imperfect of course, of taking us through books of scripture so that even in Ordinary Time the preaching has to work on this continuity of reading from Romans or from whatever Gospel or letter (harder is the present Lectionary's use of the Hebrew scriptures).

We recovered in the years after Vatican II a language long lost that understood once and can again that the mystery into which we are baptized (this Christ whom we have put on, or in other images, this Christ in whom we have died and in whom we now live) is also a name for our assembly (the church) and for the whole spectrum of rituals we are to know by heart in order to move ever further into our baptized life's calling.

These rituals are day by day (signing ourselves with the cross, pausing to give thanks at table, remembering and bringing to God in intercession) and week by week (Sunday) and year by year (fasting and feasting, initiating) and life by life (initiation, growing to maturity, sickness, death). And these also are named mystery, paschal or passover mystery, for we are not a church content with the ways of the world, or with our own ways in fact, but we find ourselves initiated little by little, even here at Sunday Eucharist, into ways to be and see and love and live for others.

Editor's note: This reflection was originally published in the May 2008 issue of Celebration. Sign up to receive daily Easter reflections.